As more time elapses since the regrettable fracas over Kitaj’s 1994 Tate exhibition and his tragic suicide in 2007, he comes more and more into his own as a great but still underrated artist. When I last wrote about him in this column, back in April, I had not yet seen the portion of his Berlin-originated retrospective which was shown at Pallant House in Chichester. Happily I managed to get there before it closed and was once again deeply impressed by the range and painterly intelligence of this extraordinary artist. Now another couple of shows pay justified tribute to his genius, this time as manifested through his printed work.

The British Museum show in Room 90 incorporates part of Kitaj’s substantial and generous bequest to the museum (293 items in total, including 18 drawings), juxtaposing it with other recent acquisitions. The argument that he would be thrilled to hang among the Old Masters he admired (there are works by Gauguin and Goya, as well as Picasso, Sidney Nolan, Auerbach and Baselitz here) is somewhat compromised by hanging Kitaj’s ‘Yaller Bird’ next to a Michael Craig-Martin drawing. Craig-Martin was highly critical of Kitaj’s return to figuration, and these old opponents do not sit well together. However, a beautiful brown ink Domenico Tiepolo drawing of a café in Venice, from c.1799, does help to redress the balance somewhat. Elsewhere there are a number of fine Italian acquisitions, including a couple of memorable landscape etchings by Zoran Music.

The Kitaj display is accompanied by a handsome new catalogue raisonné of the prints, compiled by Jennifer Ramkalawon and published by the BM at £40. This supersedes the previous catalogue raisonné by Jane Kinsman, which was published in 1994, while Kitaj still had prints to make and before a number of early works and trial proofs (which have come to light in his BM bequest) were known about. Among the very earliest prints are several black-and-white lithographs, never editioned, the best being a grinning self-portrait and a tree like a ball. In an adjacent flat cabinet is a bound copy of the magisterial suite ‘A Day Book of Robert Creeley’ (1970–2), a demonstration of versatility if ever there was one, as Kitaj experiments with materials and techniques, with collage and lettering, in pursuit of a worthy equivalent to Creeley’s writings. In other cabinets are charcoal drawings after Cézanne and a soft-ground etching portrait of Kitaj’s adored wife Sandra. Around the walls are the screenprints.

These are elaborate though surprisingly spontaneous images for the most part, carefully composed and thought out, which can occasionally be a bit cryptic or self-indulgent. But the best are seriously good, often using special paper for vigorous decorative or textural effects, juxtaposing thought-provoking imagery in Kitaj’s typical early collage style. There’s wit here, fine drawing of friends and contemporaries, radical restructuring of the components of daily living — lots of visual as well as intellectual excitement. Kitaj, though always accused of being a literary painter, was an inventive pictorial designer and colourist, and such images as ‘Republic of the Southern Cross’ or ‘The Red Dancer of Moscow’ continue to intrigue and beguile. At Marlborough Fine Art, Kitaj’s long-standing dealer, a complementary print exhibition contains many of the same works for sale.

Like most artists of analytical intelligence, Kitaj was crucially aware of his artistic family tree, part inherited, part chosen. Among the artists he cared for was Sickert, one of ‘those mad scribblers’ with whom he included Delacroix, van Gogh, Gauguin and Whistler, all talented writers like Kitaj himself. There is currently a superb exhibition at the Fine Art Society dedicated to Sickert, the most enjoyable selection of his work I’ve seen for years. Sickert is often thought of as a dark painter, a devotee of brown and putty colours, so it’s good to see here some light-filled watercolours of France and a couple of ink and watercolour cabaret studies. The darkest picture is an early etching, very Whistlerian, of Miss Helen Couper-Black, general manager of the D’Oyly Carte Theatre Company. The other etchings, still very affordable for a major artist, range over the expected subjects: music halls, interiors, Dieppe and Venice, with an occasional surprise, such as fishermen at Maida Vale, chairs in Hyde Park and an interesting counterproof of Duncan Macdonald. There are some intriguing late paintings, and fine things from earlier periods, including a wonderfully loosely handled street corner in Dieppe (c.1900); the façade of St Jacques, Dieppe’s principal church, catching the evening sun; and a bright, flag-bedecked scene of street celebrations from 1914, all lilac and pale yellow.

At the Chris Beetles Gallery in St James’s the annual Summer Show offers an expected wealth of quality exhibits, from the daringly informal plein-air studies of Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, and the romantic Ruskinian landscapes of Albert Goodwin, to the sparky fashion sketches of Muriel Pemberton. But the star of the show is Keith Grant (born 1930), a landscape painter of lyrical inventiveness whose work is insufficiently known and celebrated in this country.

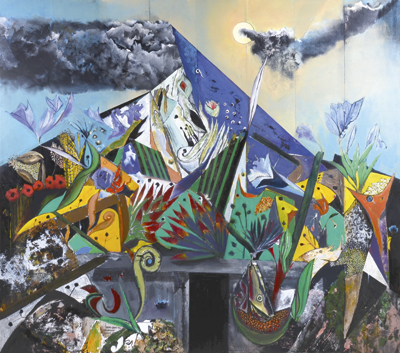

This may be because he lives now in Norway, and has taken to depicting the visual splendours of the north, from aurora borealis to iceberg. But recently he has begun to make intense, visionary paintings of the turning seasons, which have a more universal application, and which look to be among the finest works of his career. For a painter in his 80s to be renewing his art to such a dramatic extent is remarkable. Employing a post-cubist fracturing that brings a compelling dynamic flow to his compositions, Grant interprets the northern forest through recognisable features (seeds, leaves, feathers, flowers, birds), enrolling this raw material in a crisply decorative abstracted frieze, full of light and movement. There is joyous music in his angular crystalline structures: Keith Grant’s new work crackles with vitality and the passion of looking.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in