Balanced parliamentary debate was the vision of the first elected head of government in Australia, James Hurtle Fisher, Mayor of Adelaide. In 1840 he told the Governor that representative government was ‘one of the most invaluable privileges of British subjects’.

A better founding vision for the future you could not find. He was right, given the alternatives of absolute monarchy or tribalism. His speech was recorded on vellum.

The traditions of those who founded our institutions are the reverse of the open hatred expressed on our streets every weekend.

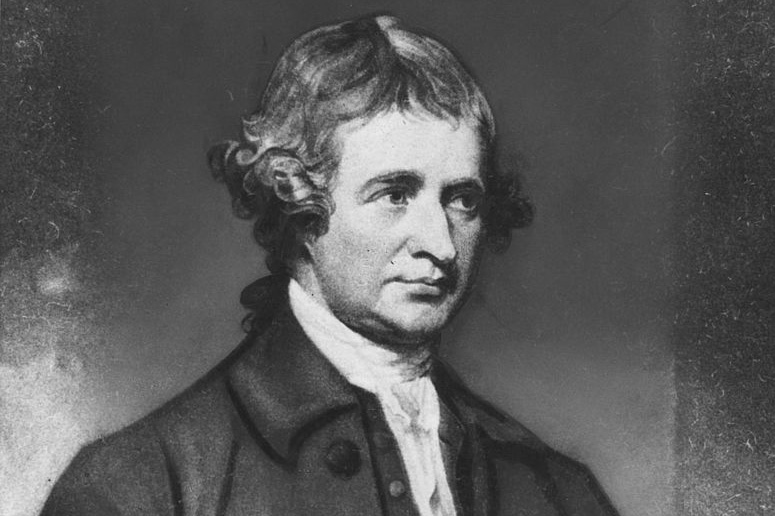

Edmund Burke defended a parliament of ‘perpetual treaty and compromise’. He expected parliamentarians to give the electors their ‘mature judgement’ and to prefer ‘their interest to his own’.

Our local political leaders campaigned for parliaments that balance all the interests of the colony during the forging of our almost uniquely early liberal democracies in the 1850s.

This is our future. Not toxic social justice theory or foreign ethnic hatred.

Books tell us that the Scots and Irish ‘saved civilisation’. What about ‘How Australia Solved Civilisation’s Problems’ – how we fed and housed desperate settlers, handled welfare, and wrote labour laws… Successful practical thinking was unusual in the world. We resolved problems through Parliament instead of shouting at each other.

We should promote anyone who celebrates rather than mourns the establishment of our country in our dead humanities.

So, what were our early leaders about? Mayor Fisher had no difficulty with our British origins. He did not have an ancestral dislike of Britain.

Fisher wanted more local freedom and supported self-government. He knew the importance of economic growth and vigorously pursued the profitable bullock transportation trade, the tractor of the time. There was a scandal about his business practices.

Like William Wentworth, he unsuccessfully opposed democracy, one obituary tactfully noting his ‘unpopular’ opinions.

But he did not believe that a violent revolution is preferable to evolution, because it is more nationalistic. He understood how difficult it was to develop the colony successfully; failure was easy.

While we were unmistakably British in 1788, we became less so as the 19th Century progressed. Although this scarcely matters. The Australian colonies developed their own unique characteristics, not only one-man-one-vote parliaments but also with remarkable comparative pastoral prosperity.

Henry Lawson’s ‘loaded dog’ chased after him with a lit explosive cartridge in his mouth, and the Heidelberg school painted Australian Impressionism.

The ‘squatters’ developed cattle and sheep empires the size of European countries, and the shearers, known as swagmen, walked the endless dirt tracks of the outback with just a swag for company. Aboriginal stockmen and labourers were essential to building our pastoral wealth, combining work with less hunting and tribal life. There was common endeavour as well as violent conflict over hunting and tribal grounds we are still arguing about. It was ‘complex’, as Megan Davis says.

Pastoral wealth was the backbone of our country. It sustained us.

Local parliaments were based on that of Britain, but more democratic. We had a one-man-one-vote Legislative Assembly in three colonies, and an Upper House, the Legislative Council, appointed or elected on a property qualification.

The 19th Century was a vastly beneficial period as well as a time of some conflict, such as the 1890s shearer strikes, which resembled to many the beginning of a civil war.

Little did the settlers know that their political settlement would be judged on the novel standards of inner-city Sydney and Melbourne. Self-hatred, undermining of Western values, and romanticising some while failing to celebrate the Anglo-Celts and migrants who made the modern world by democracy and pastoral wealth. These things are unfortunately known to our intellectual life.

They thought instead that a common prosperity and democracy was an achievement.

The Anglo-Saxon kingships may have developed from local mafia warlords who gradually increased the stock of villages that owed them ‘protection money’. (Max Adams)

Warrior origins or not, the liberal John Darvall nevertheless asked the NSW Legislative Council in 1853 for the liberties of ‘earlier Anglo-Saxon institutions’. As well as the natural rights of man, the avoidance of unrest, or representation based on population not property. But our local parliaments agreed, giving all men the vote in three colonies in the 1850s.

This gave us a strong platform for the future and freedom. But things today may go wrong.

The government has made it clear it wants to change us ‘fundamentally’ and to ‘change the government, change the country’.

Australia has begun a vast energy experiment. We pay for it in higher power prices which damage living standards and economic growth. Why not focus on economic growth and cutting government expenditure?

The use of ‘identity’ in place of hard work and merit may fade like Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat that slowly disappears:

‘Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin,’ thought Alice, ‘but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in all my life!’

If it does not, then an end date for our permanent ‘temporary’ affirmative action special measures will become more pressing. They have taken over the arts and other industries.

The main job of government must be to maintain and develop the great harvest that our young men fought for in two world wars. Read the names on the grim memorials in country towns to the those who came off their farms to die for their country before they even had a life.

‘Change the government change the country’ has to focus on economic problems and defence, and less damaging immigration. Not marginalia. That would be responsible, balanced, the result of mature judgement, the result of compromise. The reverse of the hatred expressed on our streets every weekend.

Edmund Burke understood this, as would Australia’s first elected head of government, James Hurtle Fisher, and Australia’s first Prime Minister in 1901 Edmund Barton.

The Hon. Reg Hamilton, Adjunct Professor, School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University