‘Be like the rock that the waves keep crashing over. It stands unmoved and the raging of the sea falls still around it.’ – Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Book IV

They came for him not in sequence, but all at once. Civil suits. Criminal indictments. State prosecutions layered atop federal ones. A special counsel pursuing parallel cases in separate federal districts. Each proceeding arrived with its own timetable, jurisdiction, and theory of liability, yet all converged on a single figure within the same compressed span of time.

Any one of these cases would have ended the public life of a conventional political actor. Taken together, they formed a legal barrage without clear precedent in modern American politics. The pressure was not episodic; it was cumulative. It was not confined to a single forum; it was dispersed across courts, states, and sovereigns. And it did not pause for electoral cycles or institutional restraint. It advanced continuously.

This is not an argument about innocence or guilt. Stoicism is indifferent to verdicts. Marcus Aurelius did not counsel endurance because the world would eventually be fair; he counselled endurance because it often is not. The Stoic question is simpler and more demanding: What does sustained pressure reveal about character, agency, and the limits of coercion?

Between 2022 and 2024, Donald Trump faced a legal onslaught that spanned nearly every available mechanism of modern prosecution and civil enforcement. In New York, a criminal case pursued novel theories of record falsification, carrying the weight of dozens of felony counts. In Georgia, a sweeping racketeering indictment attempted to consolidate political speech, legal advocacy, and electoral dispute into a single criminal enterprise. In parallel, a special counsel brought two separate federal indictments – one in Washington, DC, and another in Florida – each with its own factual universe and legal architecture.

These were not sequential inquiries, unfolding with deliberation. They overlapped. Hearings in one jurisdiction collided with motions in another. Trial calendars competed with campaign schedules. Appeals, gag orders, and pretrial restrictions multiplied. The aggregate exposure – if every charge were stacked at its maximum – was measured not in years, but in lifetimes.

Alongside the criminal cases ran major civil actions. A defamation and battery verdict resulted in extraordinary damages. A civil enforcement case by New York’s attorney general sought not merely penalties but the effective dismantling of a business enterprise built over decades. Each action carried its own financial and reputational consequences. None waited for the others to conclude.

What is striking is not simply the number of cases, but their simultaneity and dispersion. American legal tradition has long recognised the danger of prosecutorial piling-on. Sequencing, consolidation, and restraint exist precisely to prevent exhaustion from becoming a substitute for adjudication. Yet here, restraint was notably absent. Different prosecutors, operating under different mandates, advanced independently but in parallel, creating an environment in which the process itself became the punishment.

Historical analogies are imperfect, but instructive. Richard Nixon faced the crescendo of Watergate, yet resigned before indictment and received a pardon that foreclosed criminal exposure. Bill Clinton endured a civil suit and an independent counsel investigation that ultimately led to impeachment, but he did not face multiple criminal indictments across jurisdictions while seeking office. Eugene Debs ran for president from prison, but as a marginal figure under wartime sedition laws, not as the leader of a major party. None of these cases reproduces the same configuration of scale, concurrency, and electoral overlap.

What would a normal political figure do under such conditions? The incentives point in one direction: retreat. Bargain. Withdraw from public life. Seek quiet. Accept disgrace in exchange for relief. Modern politics is built on the assumption that reputational and procedural pressure will eventually compel compliance or exit.

That assumption failed.

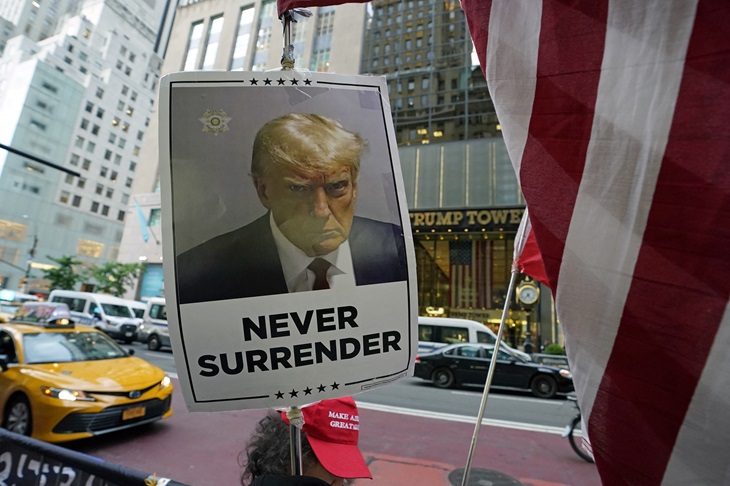

Despite the accumulating cases, Trump did not retreat. He continued to campaign. He returned repeatedly to the public arena, absorbing financial penalties and reputational damage without altering course. Whatever one thinks of his rhetoric or temperament, the behavioural fact remains: the expected collapse did not occur.

Stoicism offers a lens for understanding why this mattered. For Aurelius and Epictetus, freedom does not consist in controlling events, but in refusing to be governed by them. External forces – fortune, hostility, injustice – are to be endured without surrendering one’s inner posture or chosen path. The Stoic does not deny the pain of the waves; he denies them the power to move him.

This posture unsettles systems that rely on attrition. Modern legal and political mechanisms assume that pressure accumulates toward capitulation. They are designed not merely to adjudicate, but to exhaust – financially, psychologically, socially. When exhaustion fails to produce compliance, the system reveals its limits.

The federal cases underscore this point. A single special counsel pursued two separate indictments in different districts simultaneously, an arrangement rare in itself. After Trump’s return to office, both cases were withdrawn in accordance with long-standing Department of Justice policy regarding sitting presidents. The retreat came not because the cases had been adjudicated on their merits, but because institutional norms reasserted themselves – belatedly.

That sequence matters. The system ultimately acknowledged boundaries it had previously ignored. But it did so only after the pressure campaign had already run its course. The storm was allowed to gather and break. Only later did the guardrails return.

One can dispute the wisdom of Trump’s choices. One can criticise his language, his instincts, his style. None of that alters the analytical point. Resilience under sustained, multi-front pressure is not common in modern politics. It is not easily dismissed as bluster or bravado. It is a form of endurance that alters the balance of power between institutions and individuals.

Stoicism does not ask us to admire the rock. It asks us to recognise what happens when the waves fail to move it. Power that depends on exhaustion loses its leverage. Authority that relies on attrition finds its tools blunted. The spectacle of unbroken endurance forces a recalibration.

History often mistakes endurance for obstinacy. The Stoics did not. They understood that the man who remains standing when every incentive is offered to kneel changes the moral geometry of conflict itself. Whether one views Donald Trump with approval or disdain, the fact remains: the legal blitzkrieg did not achieve its intended end.

The waves crashed. The rock held.

Aaron J. Shuster is a writer, producer, philosopher, and cinematist. His work focuses on moral clarity, political inversion, and the intersection of history, ideology, and Western civilizational ethics.