I watched Sussan Ley’s leadership end last week. Not in Parliament – that comes later – but across two breakfast television interviews in which the Opposition Leader could not grasp that she no longer had an opposition to lead.

Natalie Barr went first, opening with a question that should have been a warning: ‘The government says the Coalition is a smoking ruin … a three-ring circus … says you can’t stand each other and you can’t work together. Which part of that is untrue?’

Ley attempted, instinctively, to pivot to the government’s failures. Barr cut her off with the exhausted patience of someone explaining gravity to a child.

‘We’re not going to talk about the government, Sussan. We’re talking about you.’

It kept happening. Ley would launch into achievements, principles, holding the government to account. Barr would drag her back. ‘We’re talking about your leadership and so is the nation. You’re in trouble. Will you survive as leader?’ Ley claimed to have landed blows on Albanese. Barr acknowledged the tough political summer but drove the point home: ‘Now the bullseye is on you.’ Put simply, the mutiny now has a timetable

When Barr asked whether Littleproud – channelling Animal from The Muppet Show – had yelled down the phone, Ley, reminiscent of Kermit the Frog at his most anxious, insisted private conversations remain private. One could almost hear the nation filing this under: yes, he yelled. Barr closed with the only question that mattered: ‘Will you be leader this time next month?’

You might have thought the schadenfreude would end there, but over at Nine Karl Stefanovic had been warming up for a go. Ley began with the same script she fed Barr – the Liberal Party stood firm on principles, we held the government to account, the Coalition is stronger together. Stefanovic stopped her cold.

‘Sussan, are you living in some sort of alternate universe? You’ve broken up. There is no Coalition.’

Ley’s response deserves to be quoted in full:

‘Maybe when people listen to meetings and abstentions and votes on the floor of the Parliament, I understand they think, what is it? That’s why I talk about our two principles. We improved Labor’s laws to have that reckoning with eradicating antisemitism, removing radical Islamic extremism. That’s actually what this was about and we’re proud in the Liberal Party that we stood firm for that. The door is open from my point of view, Karl, but I’m not looking at the door. I’m looking straight out at the beautiful landscape and communities of this country I love and the fight that I have every single day.’

Stay with me: the door is open, but she is not looking at the door. She is looking at the beautiful landscape – a line that sounds like it was written by a tourism board having a nervous breakdown. It is the political equivalent of ignoring your GP when he says, ‘Mate, that’s not reflux – that’s a heart attack.’

Stefanovic pressed on. ‘How are you going to lead a country if you can’t lead the Coalition?’ Ley listed achievements. Stefanovic snapped: ‘How long have you got before they knife you?’ Ley pivoted again – my team backs me, the door is open, the landscape is beautiful. Stefanovic thanked her for her time with the tone of someone ending a call from a persistent telemarketer.

What made both exchanges devastating was not hostility but bewilderment: Ley could not see what was obvious to anyone who had had their morning coffee. Two breakfast television hosts – whose job is to smile through cooking segments and interview lottery winners – kept asking the same question in increasingly blunt language: you do not have a team, how long until you are gone? This is what institutional collapse looks like when it is televised.

The Coalition’s second rupture since the election is now familiar enough to require no recap: Nationals senators broke ranks on Labor’s hate-speech laws, Ley accepted the resignations, and Littleproud duly declared the arrangement ‘untenable’. It was the political equivalent of saying the marriage has ‘communication issues’ while the removalist is already in the driveway. Coalitions split over policy. They do not usually unravel in opposition over process, tone, and wounded feelings unless something deeper has already failed.

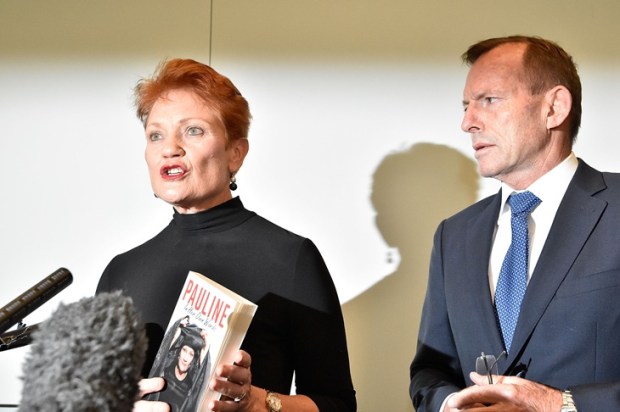

This places Ley leading a party that cannot decide whether it is regrouping or merely marking time. Polling reinforces the mood: the Coalition now sits neck and neck with or behind One Nation, which has surged to historic highs on the back of immigration anxieties and the Bondi Beach massacre. When the official opposition polls level with Pauline Hanson, the problem is existential.

Despite what the press gallery says, One Nation is not an external threat the Coalition must manage. One Nation is what happens when a conservative movement forgets how to conserve anything except its own self-image. The voters abandoning the Coalition for Hanson are not fleeing to extremism; they are fleeing from incoherence. When the official opposition spends a week demonstrating that it can neither agree on principle nor survive disagreement, voters do not become irrational. They become practical.

The entire conservative establishment has been dosed with blue-ringed octopus venom: paralysed, incapable of movement, able only to repeat ‘we’re keeping the government accountable’ while the toxin works its way through the system. They cannot articulate what they believe because for a decade they have tried to survive by sounding like Labor – only slightly less pleased about it.

Conservative parliamentarians should remember that Malcolm Fraser’s Cabinet was a collection of incompatible men held together by authority rather than affection. Jim Killen wept, quoted poetry, and ran Defence while despising nuclear weapons. Ian Macphee embodied a liberalism that annoyed his own party daily and survived anyway. Peter Baume spoke about Aboriginal affairs with a seriousness that would now trigger an internal review. They could barely agree on lunch but they governed. That kind of conservatism – argumentative, abrasive, occasionally absurd – could withstand embarrassment because it assumed politics required friction, not consensus.

Today’s conservative class treats embarrassment as terminal, which is why they select for social fluency rather than argumentative weight – figures who smooth atmospheres, reassure opponents, and avoid leaving marks.

One Nation still struggles to supply a governing conservatism. But it is legible, and in politics legibility counts. Until the Liberal Party remembers that politics is contest, not stakeholder management, voters will keep outsourcing opposition to whoever still sounds like they believe something. The Coalition is not being outflanked. It is being replaced.

Fraser governed with men he argued with, not men he found reassuring. Once, conservatives frightened their enemies and irritated their friends. Now they reassure both – and watch as voters drift away. The next Liberal leader needs less Dorothea Mackellar and more Thomas Hobbes – less landscape, more authority.