French beauty giant L’Oréal can boast its 37 luxury brands that include Lancome and Maybelline drove record sales worth 43.5 billion euros in 2024 despite the slowing of the world’s number two beauty market of China.

The company founded in 1909 can brag of profit margins of 20 per cent. It can skite about innovations such as its Cell BioPrint, which is a small device that provides personalised skin analysis in five minutes by using proteomics.

As governments can raise taxes or print money to meet bond repayments and companies can’t, this situation is extraordinary. The French government’s handicap, of course, is it can’t print money since the country adopted the euro in 1999. This gives Paris fewer means to defuse a political and financial crises that, by feeding each other, threaten to trigger the next eurozone debt crisis.

France’s torment is a political stalemate over Paris’s budget which is preventing the government from mending its finances to retain the confidence of bond investors who now judge France as the eurozone’s most precarious sovereign.

President Emmanuel Macron on Monday lost his third Prime Minister in 10 months – and second in a month – because he lacks a majority in the 577-seat National Assembly that is split roughly three ways between his centrist supporters and parties from the left and right.

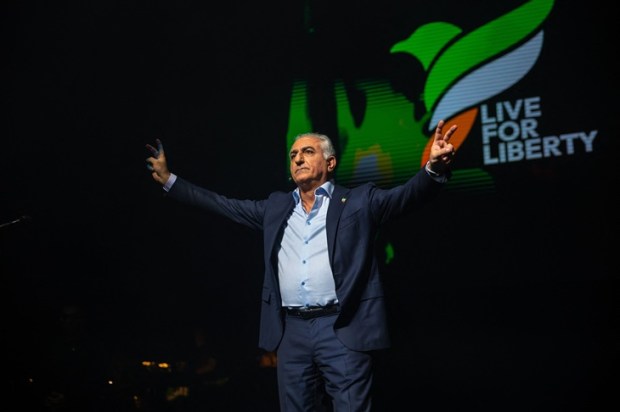

In September, François Bayrou, like in his predecessor Michel Barnier in December, lost a confidence vote he called because he couldn’t pass a budget that sought to trim Paris’s deficit from 5.8 per cent to 4.6 per cent of output.

His replacement, and Macron’s seventh Prime Minister, Sébastien Lecornu, quit on Monday 14 hours after announcing his Cabinet because opposition parties opposed the appointment of some ministers. Lecornu, having served just 27 days, thus became the shortest-serving Prime Minister of the Fifth Republic that was established in 1958.

Reducing Paris’s budget shortfall to nearer the eurozone limit of 3 per cent in the first step to slowing the rise in Paris’s debt from 116 per cent of GDP. Without such action, Paris’s indebtedness will approach the debt ratio of Greece’s when that country triggered the eurozone crisis in 2009 – Athens’s debt then was 128 per cent of GDP.

Another way to see the menace of French government debt is that, at 3.5 trillion euros, it’s the fourth highest in the world in money terms; beaten only by the US, Japan and China (while similar to the UK’s). Such a sum makes debt repayments a lethal threat to Paris’s finances if bond yields rise.

By way of contrast, Greek government debt was only 301 billion euros in 2009, which is why the damage from defaults could be contained. (Paris’s debt tally doesn’t include unfunded household pension entitlements that reach about 400 per cent of output or 12 trillion euros.)

Any new Prime Minister would appear to have little chance of passing a budget either. Opposition parties, noting the nationwide strikes and protests against reducing government largesse that reaches an advanced-world high of 57 per cent of GDP, can’t agree on how, or if, to cut services or raise taxes.

Another headache for any new government is that Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, eyeing favourable polls, appears intent on forcing a fresh parliamentary election. The right-wing party hopes to form a government and pass an ‘amnesty bill’ that would allow Le Pen to run for President in 2027 when term-limited Macron will be replaced. Le Pen is banned from seeking elected office for five years after being convicted of corruption in March.

Macron has ruled out calling a parliamentary election given the poor polling of his coalition (and his record low popularity), especially since the snap election he surprisingly called in 2024 led to today’s political paralysis. Opposition parties are calling on Macron to resign as President.

Any new government could pass a budget without a parliamentary vote via a legal loophole. But that could trigger a confidence vote the government would be likely to lose. If a new government can’t pass a budget, the budget for 2025 will roll over into next financial year. But keeping the same budget shortfall worries bond investors and rating agencies.

Investors have boosted Paris’s bond yields to 14-year highs, which means they are above those on ‘peripheral’ European countries such as Greece. Morningstar DBRS and Fitch Ratings in September downgraded Paris’s debt by one notch. Other ratings companies have signalled they will (again) do likewise, to add more upward pressure to yields.

France’s ungovernability is undermining consumer and business confidence such that the economy is only expected to grow 0.8 per cent in 2025. This sluggishness intensifies the risk that self-destructive debt dynamics will worsen the government-debt-to-GDP ratio and trigger a crisis that typically ends in default or faster inflation, or both.

Concerns are compounded by how the European Central Bank will struggle to contain any French eruption. Paris’s debt is so large in money terms, the country fails to meet criteria for intervention, and central-bank help is more inflationary these days due to the side effects (bloated balance sheets) of past rescues.

Come any political upheaval especially the rise of a populist government intending to preserve France’s welfare state, bond investors would revolt and spread France’s torment across the eurozone and beyond. While French politicians will be blamed for any crisis, blame too French voters who refuse to accept their living standards must fall to affordable levels.

Investors, to be sure, are used to France’s political shenanigans and thus haven’t overreacted to the latest political paralysis. They think Paris can meet its interest repayments that are expected to reach 11 per cent of government revenue this year – a level that was serviceable in the early 1990s. The ECB will no doubt contort itself to prevent a French default. But that would only delay the political compromises needed to make Paris’s finances sustainable.

While a political manoeuvre at the time, the warning of Finance Minister Eric Lombard last month that France is headed for an IMF bailout is likely truer than not. After all, bond investors already think that L’Oréal fulfilling its bond obligations is a safer bet than Paris doing likewise.