We often hear that the present moment is decisive. That this government, or this election, offers a chance to reset, to break with the past, to ‘get it right’. But time doesn’t work that way. Politics doesn’t work that way.

In politics, we never truly begin anew. We inherit.

We inherit laws, institutions, debt, rituals, expectations, and also mistakes, distortions, and myths. This is the concept of inherited temporality: the reality that political life unfolds within the structures and stories passed down to us. No decision is made in a vacuum. Every policy comes with a backstory. Every reform collides with the inertia of what came before.

That inheritance can be a source of strength or a dead weight.

Take our Constitution. Federated in 1901, our system of government carries the assumptions of a different era. The Crown, the Senate, the High Court, even the way we count votes. None of it was designed for a nation shaped by the internet, the rise of China, or the energy transition. Yet we’re governed by it. When calls for constitutional reform arise, they often fail. Not because people oppose progress, but because change has to reckon with institutional memory. That’s inherited temporality.

But inheritance is not just about laws. It’s also about narratives: and these are contestable.

Consider climate policy. For decades now, public debate has been steered by the assumption that there is a climate crisis: urgent, existential, and requiring immediate, far-reaching intervention. This assumption has been embedded in the education system, media messaging, corporate ESG mandates, and international treaties. It has produced entire bureaucracies, consulting industries, and subsidy regimes. It has shaped how we design infrastructure, price electricity, and define our national interest.

But what if the premise is flawed?

Many Australians sense something is not quite right. They see ever-higher energy bills, failing manufacturers and small businesses, and billions of dollars flowing into questionable ‘renewables’ projects, while reliable base load power is demonised. They are told this sacrifice is necessary to prevent catastrophe. But what they’re not told is that the science, and especially the modelling, is far less settled than the narrative suggests.

We have inherited a climate orthodoxy, a tightly policed consensus that tolerates no dissent. Like other inheritances, it did not arise democratically. It developed through a slow accretion of policy groupthink, institutional incentives, and political risk-aversion. Early climate modelling relied on assumptions that have since been quietly revised or disproven. Temperature records have been adjusted retrospectively. Dissenting scientists have been marginalised. But by the time questions emerged, the machinery was already in motion. That’s the power of inherited temporality. A theory, once institutionalised, becomes policy. Policy becomes infrastructure. Infrastructure becomes reality. And reality becomes expensive.

This orthodoxy, too, reflects a broader inheritance, not just of policy, but of psychology. It is the modern heir to an older tradition: the doomsday pattern. From medieval apocalypticism to Cold War nuclear panic, history is littered with movements that sought to transform society in response to a perceived existential threat. Climate alarmism inherits this pattern. It reframes scientific discussion as moral panic, and demands sweeping change, at any cost, with Net Zero tolerance for scepticism or accountability.

‘Climate orthodoxy is not just bad policy: it is the latest chapter in a long tradition of secular doomsday thinking. Its roots lie not in science alone, but in a deeper human pattern: the impulse to warn, to panic, and to control.’

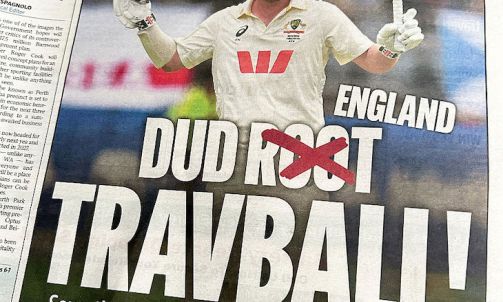

This is not a fringe view. Globally, energy crises have deepened in countries that embraced climate orthodoxy the fastest, Germany and the UK, for example. Meanwhile, countries that prioritised energy sovereignty and reliability, such as France or China, have fared better economically. Yet our political class remains stuck in inherited assumptions. To question the Net Zero dogma is treated as heresy.

This is the shadow side of inherited temporality: when we carry forward not wisdom, but dogma. Not knowledge, but narrative. It happens slowly, and then all at once. The climate agenda was not voted into existence in a single moment. It emerged over decades, driven by international organisations, elite forums, and corporate virtue-signalling. We are now living with its consequences.

None of this is to say we shouldn’t care for the environment. Conservation, stewardship, and wise use of resources are longstanding conservative principles. But the shift from care to crisis, from empirical observation to ideological crusade, is what must be questioned.

Inherited temporality also plays out in our political rituals and myths. We continue to mark Australia Day on January 26, a date that has come under attack not just from activists, but from our institutions – councils, government agencies, education bureaucracies, and corporations. Why? Because the inherited narrative of Australia as a proud, free, and prosperous nation has been challenged by a rival narrative: one of dispossession, guilt, and moral debt. Once again, inherited time is at the centre of the debate. What past do we remember? And what future does that memory make possible?

I believe inheritance or tradition matters. But not all inheritances are worth preserving. Some must be questioned. And some must be rejected.

The challenge is to discern which is which. To tell the difference between traditions that bind us together, and ideologies that impoverish us. To understand which structures were built to last, and which were built on sand.

That discernment requires time and courage. It means slowing down the political reflex to ‘act now’, and asking instead: how did we get here? Whose interests were served? What have we assumed without scrutiny?

Politics is not just the art of the possible. It is the stewardship of inherited time. We do not govern in a vacuum. We govern with the tools and the baggage we’ve been given.

And if we are to govern wisely, we must learn to say: this, we carry forward; that, we leave behind.

Because we do not begin anew.