The Australian house building (though not apartment building) industry is mainly non-unionised and therefore has low costs. But building a new house or apartment faces hundreds of different regulatory requirements. For houses, (which comprise over two-thirds of new dwellings) the most important of these is government regulation of land for building – especially on the periphery of cities.

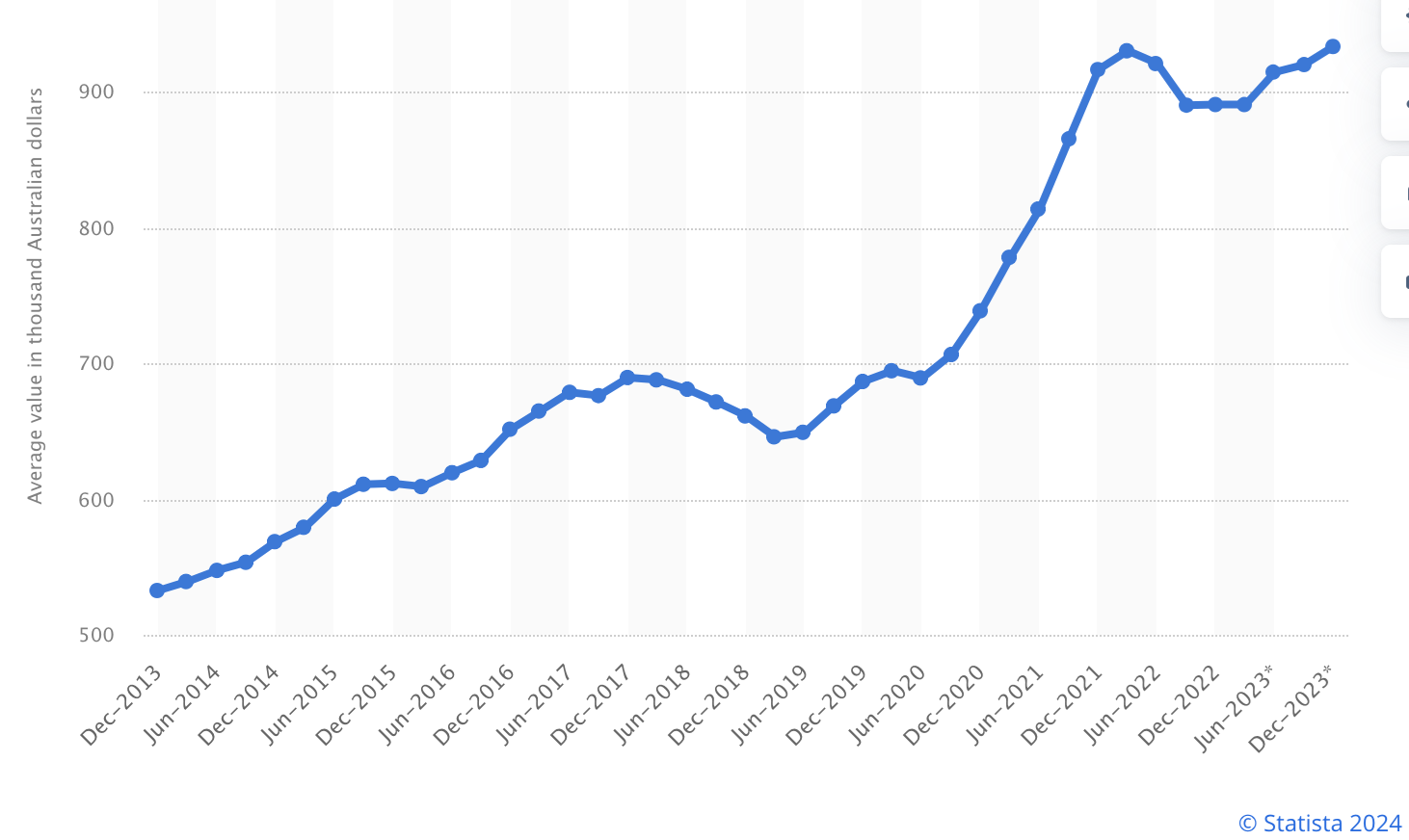

The latest Demographia Index places the cost of buying the median house in Australia at 8.2 times the median income (up from 6.2 in 2004). For Sydney and Melbourne, buying the median home requires 13.3 and 9.9 times the median income respectively. Perth at 5.4 times the median income has the cheapest prices in Australia.

In the US, the median house costs 5 times the median income and there are plenty of places, including Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Cleveland, which require under 4 times the median income to buy the median house. The difference is that in such US jurisdictions, land use regulations that prevent home building are less stringent than those prevailing throughout Australia.

Where as in California, US zoning rules are similar to those in Australia and restraint on land approved for housing creates scarcity. This raises the price of a new house block from its underlying cost (including preparation) of perhaps $100,000 to $300,000 (more than that in Sydney and Melbourne). Increased land scarcity created by regulations and other measures are responsible for housing affordability reaching Australia’s deplorable heights. The cost of unimproved land in greater Sydney is threefold its level of 15 years ago.

The two areas where governments are most dominant over the people and the economy are immigration, which the Commonwealth controls, and housing, where the states control new stock by virtue of planning laws. These dictate where, when, how, and what kind of new dwellings may be built. Dwelling construction and land preparation itself does not involve new skills, nor does it require hard-to-get inputs.

So, when the Commonwealth decides to turn on the tap for new immigrants, they would surely at the same time ensure other government agencies were loosening the restraints on land for new housing supply. Right? Wrong!

Net immigration from an average of 250,000 a year over recent decades is now running at 400,000 a year, adding 1.5 per cent annually to Australia’s population. The consequent increase in demand confronts diminished supply, with new dwellings running at around 160,000 a year compared to pre-Covid rates at 200,000 per year and below the levels 20, 30, and 40 years ago when population growth (including immigration) was far lower.

This has vastly exacerbated a supply-constrained situation that was already evident.

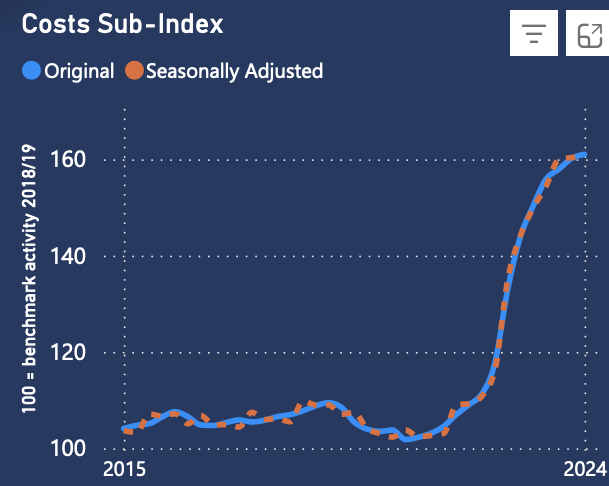

While this is mainly driven by land cost increases, the Urban Development Institute’s housing cost index further illustrates other increasing cost barriers facing wannabe homeowners. This shows input costs rising by 60 per cent since 2015, largely due to regulatory-induced shortages of wood, cement, bricks, and other materials.

In keeping with its hard-wired socialism, the government is developing a National Housing and Homeless Plan, its centrepiece being a $10 billion ‘Housing Australia Future Fund for low-income families’. The responsible agency, Housing Australia, will doubtless have great Occ. Health and Safety credentials and be adequately staffed with diversity officials and certainly opposes ‘modern slavery’. Actually, Housing Australia paid more than $24m to external consultants and $6m in annual executive salaries last year but did not complete one house. It did, however, pay its CEO a salary of $557,000 a year.

Government grants to alleviate the cost problems created by their policies are doomed to fail. There is just not enough money. The only way forward is to reform the regulations to allow an expansion of new supply.

To raise a 20 per cent down payment on a modest ‘starter home’ costing $500,000 requires $100,000. Even with a first home owner grant ($15,000) this would take younger people, few of whom earn more than the national average wage of $65,000 a year, 10 years of thrifty behaviour to accumulate. And the opportunity, like a desert mirage, constantly moves away as prices rise.

Home ownership is not only a saving for the future but it is important in providing people with a stake in and a belonging to the nation in which they live. Forcing young people into being perpetual renters or into awaiting the death of their home-owning parents will have profoundly adverse societal consequences.