Let’s indulge in some identity politics for a second: I am from Hong Kong, born as a subject of the last major colony of the British Empire, minority-ethnic, descended from Chinese refugees, now living here in exile. This summer, both the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain are presenting new displays that are meant to reflect the ‘inclusive’ and ‘diverse’ identities of Britain. Supposedly, I fit nicely among their target audience. In reality, as an immigrant looking to be included in this nation, I am perplexed by my visits. For two publicly funded museums tasked with telling the story of this country through the portraiture of its eminent figures and its art, their curators seem unsure if this is a nation worth being a part of, and if there’s a fair story to tell about it.

The National Portrait Gallery has recently reopened after a three-year, £41 million refurbishment and reworking of the building. The architects Jamie Fobert and Purcell have done an excellent job. No longer does the structure feel like a poky afterthought tacked on the National Gallery’s backside. There’s a much-needed new entrance, and the beauty of Ewan Christian’s original features have been carefully uncovered, from the mosaic floors and lost spaces to the generous roof lights. The artwork has never been seen in a worthier setting.

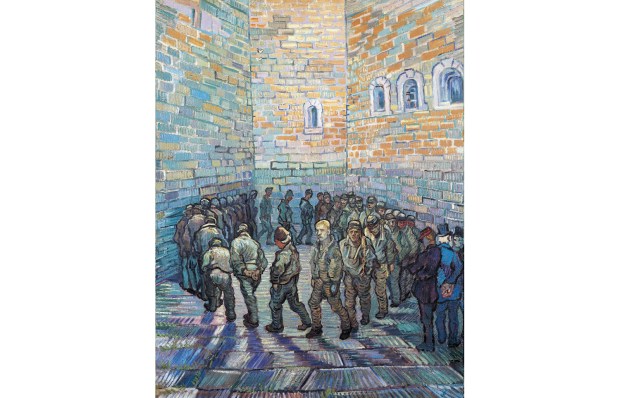

A shame then that the wall texts think so little of the artwork itself. Portraits of the long-dead are chided for their connections to colonisation and slavery. John Locke’s anti-slavery liberal theories, for instance, are caveated by his involvement in Carolina’s constitution. William Gladstone’s democratic reforms are negated by the existence of his father’s slave plantations. It’s hard to figure out what this scattershot approach to history adds to the understanding of visitors, other than serving as a nagging sign of the curators’ moral high ground. I am reminded of Mao’s Red Guards digging up the remains of historical figures to denounce them as counter-revolutionary.

The centrepiece of the relaunch, the newly acquired Joshua Reynolds portrait of Mai, a Polynesian visitor to Britain, is billed as the ‘first British painting to depict a person of colour with dignity and grandeur’. Yet the NPG already owns an earlier portrait of Mai by Reynolds’s student, William Parry, also painted with dignity and grandeur. There is, too, a curious image of Pocahontas visiting England in 1616, portrayed magisterially in Jacobean court dress.

Instead of celebrating Reynolds’s Mai portrait for its technical mastery – how Reynolds captures Mai’s pose, the structured drapery of his robes, the detail of his tattoos – the work is hollowed out and reduced to a racialised gaze.

The NPG boasts that ethnic-minority sitters now form 11 per cent of the display (up from 3 per cent). This is representation by bean-counting. The wall text speculates on the African ancestry of George III’s wife Queen Charlotte, even though the curators admit it’s circumstantial. Is this a ploy to bump up the numbers?

The older work receives the brunt of the historical revisionism. The odd modern piece interrupts the chronological flow, such as when a 1980s protest placard featuring Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian revolution, is placed among 19th-century works. Yet the reverse doesn’t happen. Why not? With a collection dating back to the Tudor period, the NPG has a rare opportunity to explain how Britain became the most tolerant, multicultural democracy in Europe. The curators take this as an inevitability. But we immigrants – who vote with our feet – know that this is not a given. Wouldn’t it paint a fuller picture of the country’s diversity if the narratives of successful minority Britons today were in dialogue with the historic pioneers who helped make embracing difference part of Britain’s story? Perhaps centuries-old portraits of those working towards Catholic emancipation have something in common with the equality campaigners of today?

The curators seem to want to tell only the obvious story: that British history is a scrapheap of shame, with the odd salvageable episode. Abolitionist figures feature as a moment of national pride in the room dealing with late 18th- and early 19th-century reformers, yet they are treated as if they were uniquely enlightened, rather than being the culmination of several historical tides. (The Christianity of John Wesley and William Wilberforce, still shared by many of Britain’s minorities, is mentioned as a mere coincidence.) The values against which history is condemned today seemingly emerge out of a vacuum and not from this very history itself. Would the gallery’s pantheon of modern Great Britons be there if not for Britain’s complex history of conflict and conciliation between pope and king, king and parliament, parliament and people, nation and empire?

There is at least a vague acknowledgement at the National Portrait Gallery of ‘complex histories’ and how the work might ‘open up conversations’. The collection has always been more about the sitters than the art, so a focus on social history is somewhat forgivable. Tate Britain has no such excuse for the first rehang of its permanent collection in a decade.

The display opens with a declaration of original sin: its eponymous founder, Henry Tate, a sugar tycoon, taints the gallery with the miasma of slavery and forced labour. I suspect the curators would rather flog the lot to pay for reparations, but legally can’t, so instead have chosen to do battle by means of zealous reinterpretation. Joseph Van Aken’s genteel portrait of Georgians drinking tea, for example, is accompanied with a finger-wagging warning of the colonial baggage of these ‘global commodities’. As a Hong Konger, my very existence was created by the geopolitics of Sino-British trade. Do I also need to come with a health warning?

The introductory video explains that art can say something ‘about the world we want to live in’ – and there are some clues as to the world the curators want you to live in. The Glorious Revolution is chided for not being revolutionary enough by Nils Norman’s mural of unrealised utopias. The ideas of the French Revolution are pined after in a piece by Ruth Ewan (born 1980) that hangs among late 18th-century works: a clock with ten hours alluding to the Jacobins’ introduction of decimalisation and wishfully titled ‘We could have been anything we wanted to be’.

Occasionally the curators remember why people visit galleries in the first place. One room recreates an 18th-century-style exhibition, every surface crammed with paintings, and no room for labels: a George Stubbs of a lion devouring a horse; a rare indoor scene from Turner, illuminated by candlelight; a John Hoppner showing sailors mooring in a gale. Here the eye is briefly allowed to delight in composition, chiaroscuro, kineticism. Filling the soaring central Duveen Galleries, meanwhile, are works that are as alluring for the nose as the eyes – Rachel Whiteread’s ghostly, tectonic plaster cast of a staircase’s void and the chiselled undulations of Vong Phaophanit’s monumental ten-tonne pile of rice. Lest anyone denounces the curators for frivolity while the world starves, however, the latter work comes with an apologetic clarification: the ‘ten tonnes of fresh rice will be donated to local food banks’.

Even the flame-haired figures by avowed aestheticists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones – who believed beauty, not morals, should be art’s defining focus – have to be bookended by displays on the Chartists and William Morris’s socialism. Ford Madox Brown’s ‘Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet’ is rebranded as a ‘socialist’ portrayal of ‘Jesus’s labour’. The long march through the institutions even tramples through the Via Dolorosa.

Elsewhere, in centring underwhelming artists for political reasons, Francis Bacon’s triptychs are shoved into a corner or made to bunk up with Henry Moore’s large-scale bronzes in a room that is too small.

The parting shot is in Tate’s Art Now room for emerging artists. Before us sits an empty acrylic glass cube, a work by Rhea Dillon that’s meant to represent everything from ‘imprisonment’, ‘breath lost stolen and from Black subjects’ and ‘environmental racism’ to ‘the link between the climate crisis and the birth of the transatlantic slave trade’. This credulity-stretching moment is a sign of a profound crisis within the arts: these national institutions have succumbed to the ever-fracturing logic of identity politics, and given up on the possibility of creating any sense of commonality through culture.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in