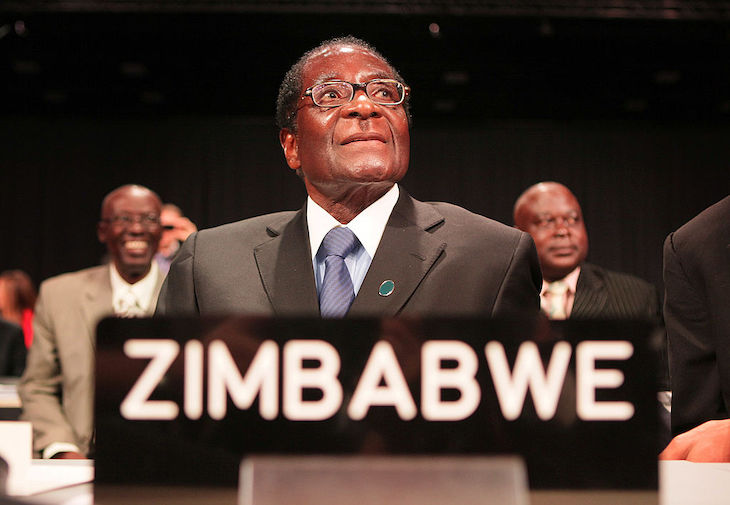

A century ago today, Robert Mugabe was born. The man who would come to rule over Zimbabwe between 1980 and 2017 was a brutal and autocratic tyrant. Mugabe shattered his country’s economy, oversaw vicious human rights abuses and left public services, especially healthcare, in ruins. But while Britain would ultimately see Mugabe as an adversary, it played a key role in his rise to power.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in