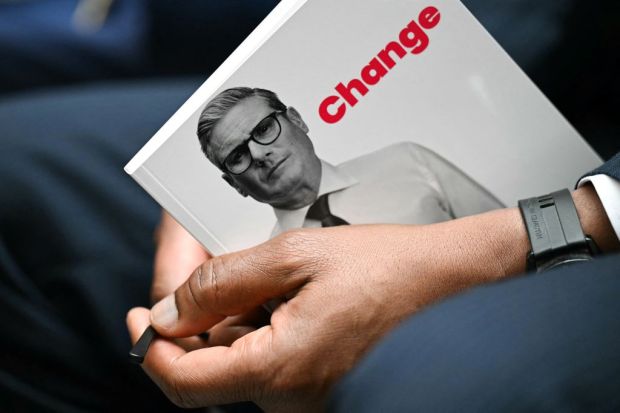

War rhetoric is everywhere in our volatile politics: from Ukraine to the resurrection of the war on terror in Gaza, from the ‘wars’ on human smugglers, drugs and crime, through to more metaphorical culture wars, ‘war on motorists’, on a virus – even on climate change. Keir Starmer accuses Rishi Sunak of prosecuting a ‘one-man war on reality’ while ‘anti-woke’ campaigners decry a war on Christmas.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in