The present Queensland government’s Water Security Plan includes doubling the present capacity of the existing desalination plant at Tugun, and the building of a new $8 billion desalination plant in the Sunshine Coast region. However, the water production data and the historical rainfall records make it abundantly clear why neither of these proposals should go ahead.

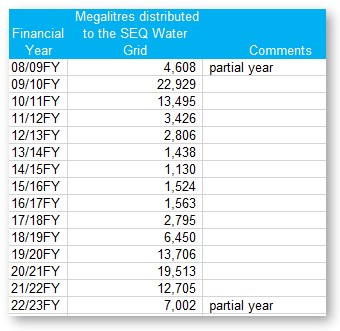

The existing Tugun plant was completed in 2008 at a cost of $1.2 billion, but it has produced almost nothing over the last 15 years; an average of just 6 GL of water per year despite having an annual nameplate capacity of 45 GL. Most of that water was produced after droughts in 2007 and 2019; 36 GL from 2009-2011 and 47 GL from 2019-2022; just a third of the plant’s designed freshwater potential (see table below provided by SEQW). During the more ‘normal’, non-drought years that characterise South East Queensland, the plant has been on care and maintenance, making just enough water to keep the equipment ready for use.

Record of Tugun Plant Desalination Water Production

Yes, desalination technology is tried and tested, and yes, where no alternatives are available it makes a huge contribution to drought-prone lands. Israel gets 55 per cent of its domestic water from desalination. Other Mediterranean climates such as California, Perth in WA, and South Western Africa find desalination an essential ingredient during the growing season. Their rain falls mainly in the winter, and either soaks into the ground or flows out to sea, unless captured behind dam walls.

The last dam to be built in Australia, the much smaller Wyaralong Dam, was completed in 2011 following the drought of 2007 to provide drinking water to the South Brisbane area. The new plan includes the building of a water treatment plant downstream from this dam and tying it into the South East Queensland water grid.

The prevailing winds on the East Coast of Australia are from the south-east and bring lots of moisture to fall as rain on the eastern side of the Great Dividing Range, but the area suffers periodic droughts which, together with the large increase in immigration and a lack in new dam construction, is putting more pressure on the water supply system. Thus, it seems at first sight, reasonable to build a new desalination plant. However, the rainfall record shows that these droughts are about as common as heavier-than-average rainfall and flooding.

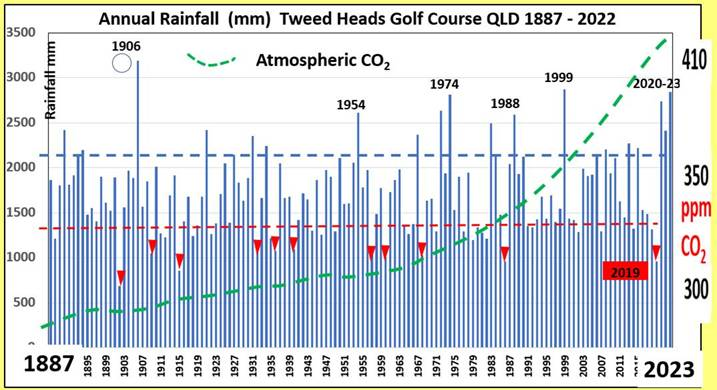

The records of the Tweed Heads Golf Club near the NSW-Queensland border are typical of much of the East Coast, and are shown in the graph below; short sharp droughts followed by short periods of above average, heavy rainfall – followed by several years of neither extreme. Much of the rain that falls in the wet seasons, overfills the few existing dams and flows out to sea. After the devastating flooding of Brisbane in 1974, a dam was completed in 1984, at Wivenhoe to the west of Brisbane, but was designed more as a flood mitigation project than for water storage. Yet Brisbane City flooded in 2011, and again in 2022, after long periods of heavy rain.

Annual Rainfall Tweed Heads Golf Course

The dashed green line is the apparently unrelated rise in global atmospheric CO2 concentrations in ppm; serious drought years indicated by red triangle, with the driest in 1902; there is no trend in the frequency of droughts or heavier than average rainfall.

The 2007 drought was seen by some as a symptom of global warming, which was only going to get worse and desalination plants were quickly installed in almost every state. Their hasty construction was based on the advice of climate ‘experts’ while popular culture often quotes Tim Flannery, who warned that the Warragamba Dam in NSW, would never be full again and that any rain that fell would probably evaporate before reaching the parched earth; none of this happened. Yet here we are again trying to outsmart nature on the basis of another expert’s warning of a threatened drought.

Queensland’s population has more than doubled since the Wivenhoe dam was completed, from just over 2 million in 1984 to 5.4 million in 2023, almost tripling water demand; an increase that another, intermittently useful and expensive desalination plant will not resolve. One would have expected Palaszczuk’s Cabinet to look at the existing rainfall and desalination records, rather than listening to the armchair advice of so-called climate change ‘experts’ who seem to forget that their frightening predictions have never come to pass. Dams are, perhaps understandably, disliked by the left-leaning, well-meaning tree huggers due to their negative environmental impact, but these same people seem to have lost their focus, as they appear to love the much larger environmental footprint of wind and solar – in the name of saving the planet.

We are told that this new desalination plant, like the one at Tugun, would provide insurance against future droughts, but the former has spent most of its life on care and maintenance, and is already over halfway through its design life. Current running costs have been ‘guestimated’ at perhaps $15-20 million per annum, for almost no useful return. The rainfall pattern on the Sunshine Coast is just the same as on the Gold Coast, how will the new plant fare any better?

A different but equally failed attempt to bolster Brisbane City’s water supply was the $2.7 billion ‘expert’ recommended’ Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme, opened by the Beattie government in 2007, but left largely dormant, with no immediate plans to recommission.

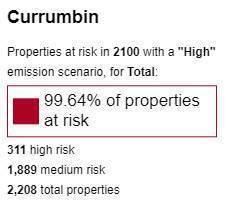

Reliance on experts is a constant ‘justification’ for government decisions, despite their hopeless track record, is now worried about too much rain, so why must we build a desalination plant? So confident in their prediction, one climate council claims that most properties in the eastern seaboard of Australia (including the Tugun Desalination plant near the airport) will soon be ‘uninsurable’. Estimates for Currumbin in the link below are based on unproven assumptions as to the effects of human emissions on ‘Climate Change’.

Climate Council’s prediction for properties at risk in Currumbin by 2100

I hope therefore that the government thinks again and takes the ‘expert’ advice with a pinch of desalination salt…

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in