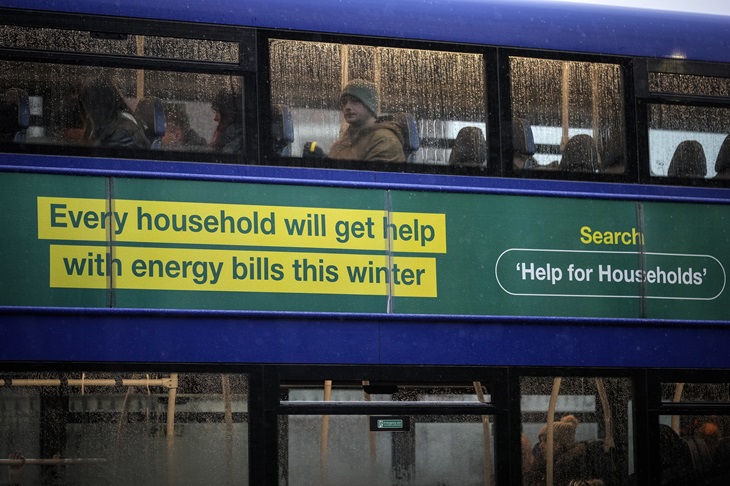

The cost-of-living crisis in the United Kingdom (UK) has severely worsened during the Covid era, pushing households into financial hardship and the looming prospect of poverty. According to a recent survey conducted in February 2024 by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 46 per cent of households reported an increase in their cost of living compared to the previous month.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in