In 1299, Amatino Manucci, a Florentine helping to run a merchant’s business in Provence, kept at least seven ledgers and notebooks, each serving a specific purpose. One covered the firm’s trade in wool and cloth, another in wheat, barley and other victuals, and so on. It wasn’t just figures Manucci worked with. It was also financial concepts, quite advanced by the standards of that time: accounting entities and periods, profit and depreciation – notions that heralded the invention of accounting as we know it. ‘If you’ve ever tapped numbers into an Excel grid,’ Ronald Allen writes in his engaging popular history, ‘you have Manucci and his contemporaries to thank – or blame.’

Allen considers the notebook in its various forms, from the wax tablet to the electronic spreadsheet, and from early modernity to the present day. Why, despite the digitisation of everything, do many of us still choose to write and draw on paper? This question is constantly on Allen’s mind as he makes forays into art and science, self-help and politics, tracing the relationship between power and information technology over the centuries. His research is based on a variety of primary and secondary sources; his writing has the lightness of touch needed to turn the dry pages of notebooks into living historical documents.

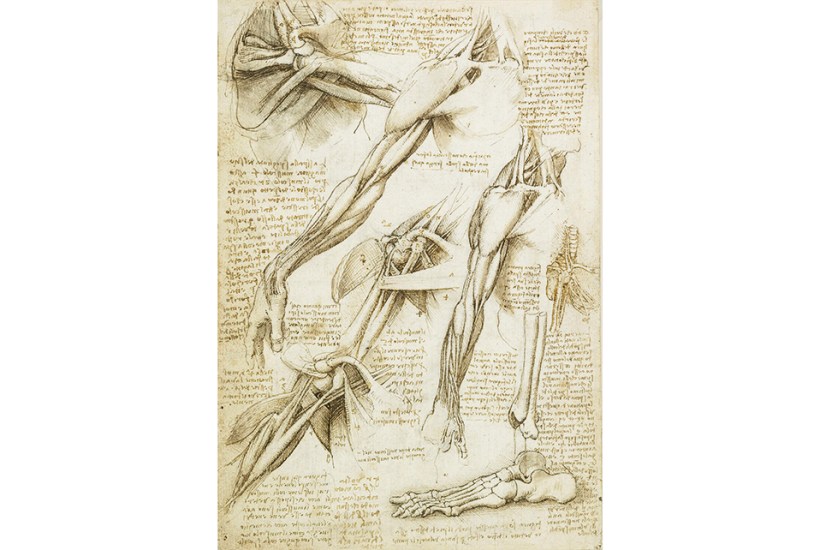

Italy is often in the focus: Florence, Venice, Genoa – places whose natives once dominated European trade. These agents of progress developed much more than sophisticated book-keeping techniques. We visit the Italy of Leonardo da Vinci, who advised his fellow artists to ‘take a note…with slight strokes in a little book that you should always carry with you… preserved with great care’, and of Marco Polo, whose account of his travels, Il milione (a word he coined, according to a legend, to describe a very large number), was often excerpted in zibaldoni, Florentine personal anthologies popular in the 14th and 15th centuries.

From Renaissance Italy we travel to northern Europe, whose inhabitants kept ‘friendship books’ for their acquaintances to leave epigrams and signatures in. These often proved useful. In 1535, for instance, a killer was acquitted thanks to an inscription Martin Luther had made in his book. What was once called the album amicorum became the poetry album and the autograph book, before culminating in the social media profile. Here, the question of digital vs analogue is dropped – only to reappear in later chapters.

On to 19th-century Britain and its law- enforcement institutions. Approaching the black police notebook, Allen is looking for a ‘tale of methodical detection’; instead, his source tells him, ‘notebooks are about control of the copper’. When London’s Metropolitan Police was founded in 1829, ‘the constables, who mostly patrolled at night, weren’t trusted not to slack off’, and so they had to log their movements in notebooks. As we move on to the 20th century, the police notebook becomes ‘a form of evidence that [is] particularly vulnerable to tampering’. Today, as digital devices increasingly take over, ‘we should be grateful that the traditional paper notebook is being removed from service’, hopefully to prevent deception and corruption.

Most notebooks, however, play less sinister roles in our lives. Allen talks of patient diaries, including the one kept by the writer Michael Rosen while he was gravely ill; of notebooks used by musicians, among them Brian Eno and Bob Dylan; of old ship’s logs used by climate scientists. In many cases, old-style notebooks do get converted into computer-friendly formats, and yet the physical object is still very much alive. The Notebook may not offer a full explainer of the race between paper and silicon, but the fascinating stories it tells certainly make you want to take out a pen and jot down a few points.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in