When you think of a collector you might imagine, say, Sir John Soane, Henry Wellcome, Charles Saatchi or Peggy Guggenheim, the fabulously wealthy, amassing their statuary, paintings and penis gourds in order to furnish their Xanadu palaces or display their good taste and fortune for the benefit of the nation. But there are other kinds of collectors: normal people.

Most of us at some point have had a little collection on the go – stamps, pebbles, gonks, succulents, Pokémon cards. I remember at school there was always great competition for Panini football stickers: everyone seemed forever to be in search of the elusive Kenny Dalglish.

Of course there will always be hoarders of knick-knacks, old tools, novelty nut-crackers, Northern Dairies milk bottles and goodness knows what else. I know someone who collects toenail clippers and another who collects snow globes and embroidered slippers – a mini V & A in the making. My uncle Dave used to search for those Bell’s Whisky ceramic decanter things. Charles Kane he most certainly was not: Dave was a minicab driver from Basildon.

Paper ephemera is perhaps the most delightful and affordable stuff for the average person. It’s cheap, durable and doesn’t take up too much space. No need for your Hearst castle, or even a drinks cabinet or shelf above the sideboard: you can keep your collection of pre-war bus tickets in a ringbinder in a drawer. The curator Ingrid Swenson preserves her collection in a dozen black presentation folders.

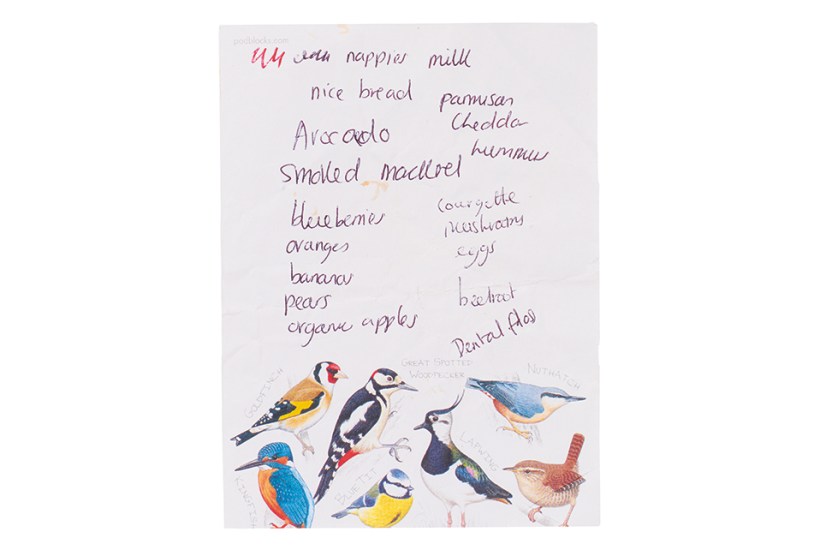

Swenson has amassed other people’s shopping lists. Her book is a beautifully produced catalogue of this collection, though catalogue is perhaps too strong a word. It’s just a small, dense, thick book full of colour reproductions of the hundreds – in excess of a thousand – of shopping lists found by her at the Waitrose on the Holloway Road in London over a period of about ten years, plus a few pages of explanatory text. You might think such a book would be simply silly: at best, an early Christmas stocking filler. But in fact it’s unputdownable, like a series of notes towards Beckett’s short plays. I found it much more interesting than some of the novels on the current Booker shortlist.

‘Almonds, asparagus, chillis, wine in Whitstable.’ ‘Milk, bread, eggs, rolls, veg – green beans (org), TURK.’ ‘Scallops Sardines Bread Broc (2) Soup PorridGe.’ It’s not difficult to understand why this stuff appeals. There’s the obvious odd aesthetic value: the vast array of colourful Post-It notes, the index cards, the backs of envelopes; and the incredible range of handwriting on display. (One important lesson from the book: penmanship has gone to pot.) But there’s also that rare glimpse into other people’s private lives: someone’s entire world, in Swenson’s words, ‘captured in a single, modest entity’. It undoubtedly helps that Swenson refrains from offering any grand theory or set of interpretations in her commentary. There’s no mention of Walter Benjamin, tempting as that must have been, no pontificating about cultures of consumption and obsolescence, no banging on about our archives of the self. She suggests merely some of the information that we might wish to infer from the limited data that the lists provide: age, gender, dietary habits, profession. Who exactly is buying ‘moose bread pastries chicken vodka + fags’? Or ‘Salt Nibbles Milk Cherrios Bunnies Burger Buns’?

She may not labour the point, but hers is undoubtedly a heroic task. We all know that in the end most of us will leave no trace; there’ll be little or no evidence that any of us ever existed. And, besides, the written shopping list as a part of our everyday lives is disappearing:

As life becomes more digital, more efficient and more ecologically aware, the shopping list as a quotidian fact of life, like so many everyday items, sounds and smells, is gradually dying out.

Swenson has been gathering our remnants, in several senses.

Behind all collections one can catch a glimpse of the collector: even today, Sir John Soane seems to inhabit every inch of his museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Swenson reveals in the final pages of her book that the shopping list project – begun in 2014 when she picked up her first crumpled note – ended last year, after she left her job of 23 years and embarked on life as a freelancer, and no longer found herself visiting Waitrose as often. If nothing else, Shopping Lists provides a reminder of a world that was – a time when ordinary Londoners could afford to buy, say, mozzarella and beer. Extraordinary.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in