It’s been a long time coming, Patricia Cornelius’ My Sister Jill but she’s a playwright whose work demands to be seen. Cornelius is the only dramatist you could imagine doing a version of that towering play, Lorca’s The House of Bernada Alba as she did a few years ago and she’s the only one who would dare to invoke the title of George Johnston’s My Brother Jack with all its pent-up masculism. Well, masculinity and the sufferings it endures and the ones it inflicts are the subjects of Patricia Cornelius’ play. The father in this story was a prisoner of war in the notorious Japanese prison camp Changi and the whole play which spans the end of the war to that very different time of war (the resistance to the Vietnam war) is a reflection through whatever dark glass of artifice of Cornelius’ childhood in which an outraged and by necessity damaged father played by Ian Bliss physically savages his sons and lords it over his wife, the magnificent Maude Davey. Sam Neill said recently – thinking of his father’s wartime experience – how governments after World War II used to explicitly caution familes ‘Don’t ask’ because the price of the answer could be terrible for everyone involved. My Sister Jill allows for the distorting hero-worship of a daughter for her father as well as the opposite nightmare where another sister can see nothing in her mother but a cowardly obeisance towards a man who has surrendered to his inner bastard. And, of course, how in any easy way is she supposed to escape from the carapace of the maternal role the post-war world offered to her like her own head on a platter. Patricia Cornelius is one of the toughest, most hard-hitting playwrights we have and the prospect of My Sister Jill has been a light in the dark of the tunnel since (and all through) Covid. The Melbourne Theatre Company is lucky to have an actor of Maude Davey’s stature as the mother and the direction is by Cornelius’ fellow warrior Susie Dee.

Meanwhile as the nation is seized by different perspectives on Aboriginality and the question of the Voice that very grand Indigenous dance company Bangarra has been performing Yuldea and the company’s new artistic director Frances Rings has been intent on giving choreographic form to a terrible saga of how the settlement of this country produced anguish and desecration as the Anangu people were scandalously pushed out of their land as a consequence of those nuclear tests which we so blithely and blindly tolerated. This very grand dance-work begins with an archetypal representation of the great and stately stars in the sky – immemorial in their unchanging power – only for this to yield some crashing and crazy heavenly thunder that seems to anticipate – to prefigure as prophecy the humanly engendered horrors – to come. From here there is wandering, the Anangu people lost until they find the magic and the nurture of the waterways. There are the gorgeous dingo ghosts who show the way and the great semi-circle of ropes that ensures proximity and intimacy and a hope that is symbolised by how close the spectator gets to the dancers. And then the modern world is presented through the symbolism of the shackled monsters but we know that unleashed monstrosity awaits. There is the solitary dance of death performed as an enactment of the loneliness of desolation by Rikki Mason, a spot beating down like the portent of mutation caused by the nuclear neglect. There are also superb and dramatically expressive duets of a high order. Yuldea is not a perfect or perfectly coherent work of modern dance drama but its generalised power has great authority.

While we’re on the subject of national self-expressiveness it was weirdly fitting that the great Ron Barassi – the man who shaped four football clubs Melbourne, Carlton, North Melbourne and the Sydney Swans (and re-invented AFL football) should die in the lead up to the stunning Grand Final where Collingwood beat the Brisbane Lions by four points. I thought of my dear dead friend Jill Singer interviewing him – brilliantly – and asking him if he ever cried and Barassi saying to her that yes he did and the last time he cried was at the funeral of Robert Rose, the quadriplegic son of the great Collingwood coach, Bobby Rose. I thought of her too lecturing in Vietnam, in the former Saigon, and causing her students to titter nervously, when she said, ‘As a journalist it is your duty to examine the government and where necessary attack it.’

By the way, on Grand Final night we were suddenly in the lustrous seat of Kooyong cast into total darkness at 8.30pm. All we could do was go to bed and watch on the iPad Gabriel García Bernal play a gay wrestler in Cassandro (on Amazon Prime). He’s done Lorca, he’s made masterpieces by Almodovar but what a strange end to the footy.

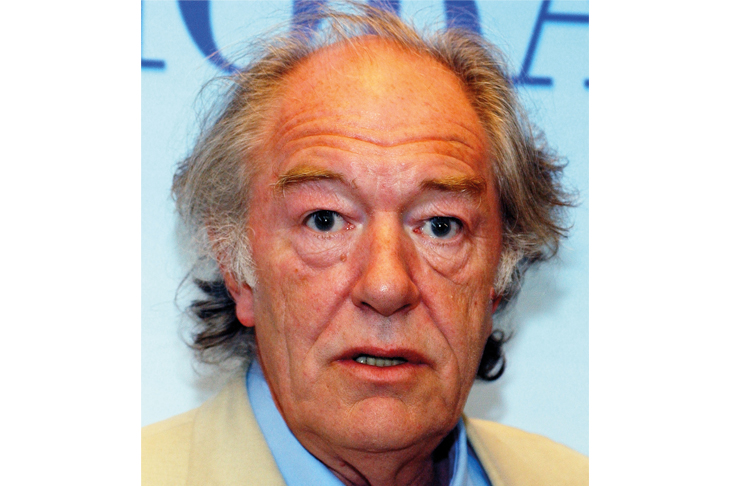

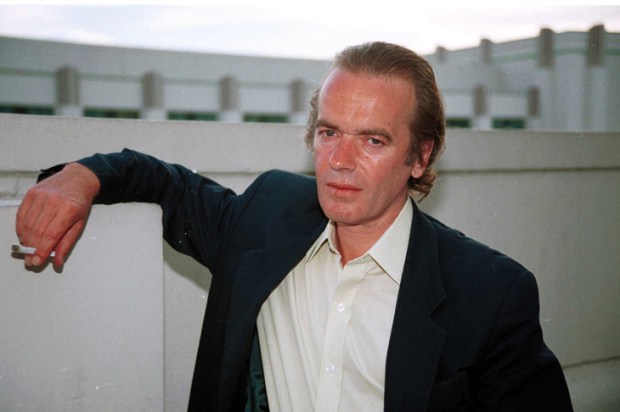

It’s saddening that Michael Gambon died last week. He’s one of those British actors the millenial young know for the simple reason that he took over from Richard Harris as Dumbledore in the Harry Potter films. But he was one of those character actors who shone brighter than most stars. He became internationally known for The Singing Detective that extraordinary mutant masterpiece by Dennis Potter but he was great doing Pinter, great doing Ayckbourn. And he could take on the impossible roles like Brecht’s Galileo and the Falstaff, Shakespeare’s greatest comic character because he has the touch of the tragic inasmuch as Prince Hal can break his heart. He was also a Lear who could defy the raging wind and the hurricanes because he found them within himself and he had a very distinguished Fool in Antony Sher who wrote a book about the production. But Michael Gambon was such a convincing Lear because he could do anything as an actor without finding himself remotely glamorous.

One final sombre note. The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra are playing Deborah Cheetham Fraillon’s Eumeralla, a war requiem for peace with the Dhungala Children’s Choir on the very night the referendum vote is counted, 14 October. At the Fall of France all that could be heard on French radio was Berlioz’s Requiem.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in