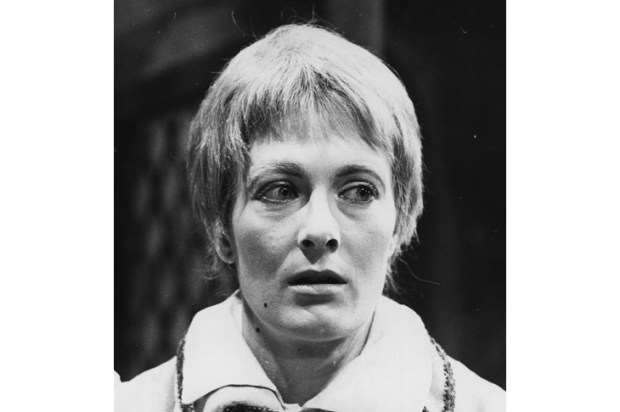

Miriam Margolyes was not wrong – however intrepid she may have been – to remark to Her late Majesty the Queen that she was the finest spoken-word actor in the world. Well, certainly one of them: she has recorded the whole of Oliver Twist, the whole of Bleak House and she has brought her power to bring alive a world of voices to that extraordinary work Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie the film of which won Maggie Smith an Oscar for the title role in 1969. Dame Maggie once remarked that Professor McGonagall was just Jean Brodie in a witch’s hat. Miriam Margolyes will be telling stories about her brilliant career – she was the Vanderbilt-like matriarch in Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence and stole the show as the Latina nurse in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet and by some miracle she turned into the blonde Sapphic stately figure of Miss Wade in her one-woman show Dickens’ Women. The Oxford High School once approached Miriam to ask Maggie Smith if they could name a theatre after her. Maggie Smith is remarkably dry of speech – she had been known to refer to Sir King Bensley and Richard E. Cant. She said to Miriam Margolyes of their alma mater, ‘I always hated the f–king place. Tell them to name their theatre after you.’ So Miriam reported and, as a consequence, so they did. She’s talking at Hamer Hall on 22 March.

14 and 16 March saw the head of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Jaime Martin hurl himself and his troops into Mahler’s Third – that extraordinary lyrical work with its evocations of a blessed humane spirituality – with the assistance of the Young Voices of Melbourne choir and the American soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis. Mahler’s Third is a work of shaded majesty and of the glory of nature and it is therefore suited to the intense dramatic extroversion of Jaime Martin’s conducting. Mahler is the composer who carried the spectacular innovations of Wagner a degree further, pointing the way to a contemplative idiom of extraordinary emotional range as well as technical experimentation which taken to their logical extremity would lead to the innovations and iconoclasms of Schoenberg. In the Third, Mahler is very much the late Romantic using his vocal forces to dramatise the glory of life. It’s remarkable how Mahler persisted with the supreme moodiness of symphonic form where his great contemporary Richard Strauss wrote opera after opera – from the fiery vehemence of Elektra (with its Hofmannsthal rewrite of Sophocles) and the equally startling animation of Oscar Wilde’s words in Salome to the mellow serenities of Der Rosenkavalier. If you want to see Jaime Martin in rehearsal, improvising and honing his sense of musical skills there’s his open rehearsal on 19 March at Hamer Hall.

Martin is conducting that supremely popular work Holst’s The Planets which is a seven-part tone poem in which the characters of the different planets are evocated. It was in fact completed before the Great War and the horror and carnage of the trenches and the Western Front but the sound of Holst’s Mars had a terrible premonitory quality just as the Jupiter seemed to express the lyrical and fragile beauty of an impassioned loveliness in the face of every terrible thing. It is the source of that glorious piece of music ‘I vow to thee my country’ which is always being used in some le Carré-style ambiguity – about Burgess or whichever of the Cambridge spies – because the very idea of what a country might be (and what kind of loyalty it might command) had become problematic.

The cello concerto of Elgar – ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ man – is being performed by Alban Gerhardt, conducted by Jaime Martin on 22 March and is also part of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s morning programme. It is often thought of as his greatest work and there is an irony that the hymn to Empire – memories of the young lions of Ormond College standing on the table in their formal gear to sing it like an anthem of triumphant establishment culture – should have produced such an extraordinary expression of disillusionment. It’s as if the first world war produced in Elgar – the master of the Enigma Variations – a sense of the most profound loss. There’s the suggestion that an empire is never so great as when it weeps for its dead, that the elegiac mood ultimately sweeps the board.

Where does that leave the MSO’s spectacular attempt to mix it with the popular when it gives concert performances of Star Wars: The Return of the Jedi. This is certainly one kind of music of Empire and it’s worth noting that John Williams, that supreme master of the popular, takes his bearings from Mahler and, more particularly, from Richard Strauss. And the kids are going to get a sense of what a score can do when they see it performed in accompaniment with George Lucas’s film that came with such an impact of chivalry and villainy when we first saw it with Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi and James Earl Jones’ voice animating the sepulchral Darth Vader. You can see it from Thursday 18 April to Saturday 21 April.

On 27 April we get another popular feast, the final performance of Kate Ceberano’s My Life is a Symphony in which the Australian songstress goes from pop hits like ‘Brave’ and ‘Pash’ to haunting ballads like ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’.

Mary Magdalene’s song from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar is a reminder that Easter looms. On Saturday 6 April, Bach’s St John’s Passion – the slightly lesser known of Bach’s two towering enactments of the Crucifixion – is performed at Hamer Hall as the culmination of the baroque festival.

Add to this that the Australian Ballet’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland runs from 15 to 26 March at the State Theatre and it is marvellous that a great company can invoke such a supreme work of comedy and fantasy as Lewis Carroll’s extraordinary take on the Victorian age when Empire loomed supreme.

Worth noting too that David Hallberg the very formidable head of the Ballet hosted a conversation at the State Theatre Lounge on 16 March. He is a ballet magus spanning all things classical and modern who brings to mind Yeat’s phrase about ‘the fascination of what’s difficult’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in