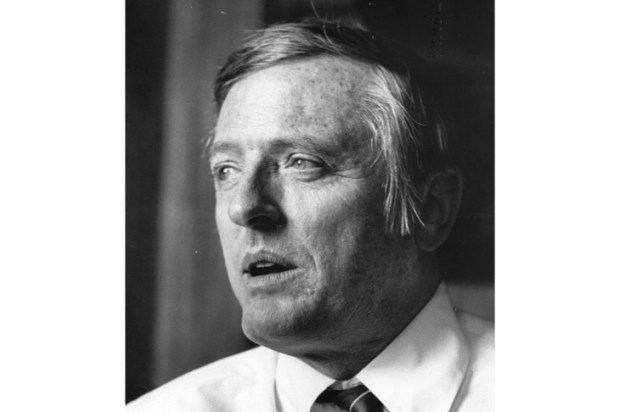

A refreshing and humbling prospect, in a world where we sometimes imagine cultural coverage gets better, is to revisit the the legendary interviews Dick Cavett did in New York fifty or more years ago. You can see him talking to Groucho Marx and how that great comedian wishes he had had a better education. You can listen with awe as Hitchcock says Psycho was luxurious fun or watch Brando, in the wake of sending a young Indian woman to the Oscars in his stead, claim we’re always acting all the time.

But the impulse to be interviewed by Cavett is irresistible to some of these extraordinarily grand figures to whom he pays such lavish and artful homage. Orson Welles in what must be one of the greatest interviews ever conducted is nothing like your memory of his immense booming presence. He says he can’t stand being interviewed by people who put their Orson Welles hat on to talk to him. The man who made Citizen Kane as a boy and terrified New York with his War of the Worlds broadcast says that when he sees bits of his films he can only see what’s wrong with them: the score, for instance, in the mirror scene of The Lady from Shanghai. He also tells extraordinary stories about famous figures. He sat at a table in Innsbruck with Hitler and thought there was no one much there, just another extremist crank. The person he most admired was General George C. Marshall, the head of the US Army during the second world war because he saw him befriend a young boy who was thrilled to meet him at a party full of the world’s top brass and talk to him by himself for half an hour.

He’s very funny about the fact that Cavett was originally an actor and the way he will never refer to his rivals like David Frost. It’s an utterly unbuttoned racy, down-to-earth portrait of a supreme genius and it has none of the trappings of fame or the bravura. When Cavett says he once worked for Jerry Lewis – has he heard of him? – Orson Welles says, ‘A dull gong sounds,’ and then says this sounds like bad Noel Coward. He then gets stuck into Lewis for using technical language when plain worlds would do. Cavett says – not missing a trick – that he can testify to the veracity of this. The whole interview is captivating and it makes you proud of what our civilisation is capable of and sorry for what we have lost. When Cavett asks Welles what two films he would preserve he says, stumped, ‘Renoir’s La Grande Illusion and something else.’ Then he details a film called Something Else.

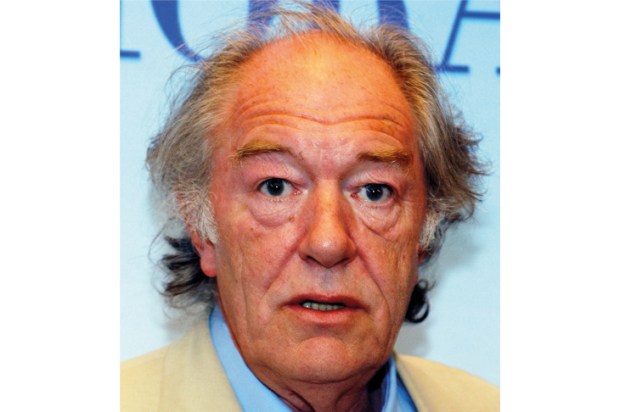

Cavett is an absolute master, constantly presenting himself as a simpleton in order to get maximum effect and shade and light. There are two hours of Richard Burton at his most rhapsodic and anecdotally grand. He says Olivier’s voice is like a silver trumpet whereas his own is a baritone. He talks about the battle with the bottle and says that when the critic Frank Rich said he covered a whole octave with one word it terrified him and made the word an impossible mountain for him.

Then there’s Katharine Hepburn. Before she agreed to be interviewed by Cavett – at the time of the American Film Theatre’s production of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance – she had never done a full-dress interview about her life and the fact that she opened up to Cavett made him an object of envy to the Barbara Walters of the interviewing world.

The conversation – which goes for two hours – starts in the midst of its own preliminaries. Hepburn says, ‘Let’s do it,’ and Cavett is utterly straight, not overtly naive at all. She delights in retelling the story of Dorothy Parker saying that she, Hepburn, ran the gamut of emotions from A to B – and adds that it wasn’t true, she was actually stuck on A. There’s a wonderful portrait of Spencer Tracy and the way his supreme naturalness filled other actors with awe: it terrified Sidney Poitier when they did Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?. She says Tracy had Irish dreams and difficulties.

She makes it clear that she treasures her intimacy with Tracy without directly confessing to the enduring depth of their love affair. She pours out the story of her life like a magic potion and you have the weird sensation of witnessing the self-disclosure of someone who doesn’t natually do this sort of thing in public. She says that she was the one who got dysentery making The African Queen; her co-star Humphrey Bogart and director John Huston were protected by drinking nothing but liquor.

She’s tough as nails and utterly volatile. She tells of the story of hitting Peter O’Toole during the making of The Lion in Winter because of a dispute over a make-up assistant: O’Toole came back on the set with crutches and bandages.

Clive James, in his famous but rather more studied interview, hears her tell this story and elicits the sad fact that her brother’s death by hanging seems to have been a bit of pleasure gone wrong. He also pushes her on Spencer Tracy – and she warns him about the direction he’s going in – but the version on YouTube cuts the staggering long silence she held when she didn’t like his question.

It’s so easy for us to take for granted aspects of our popular culture which look like the lost treasure of a vanished world when we revisit them. This is certainly true of the Dick Cavett interviews which have the truly disconcerting quality of finding the naked self behind the highly cultivated persona.

They are interviews with people of extraordinary glamour and objective achievment. Sometimes the upshot is not altogether attractive: Brando, say, has a hauteur that is just a bit self-aggrandising. Hepburn, of course, says he is a very great actor even though she’s less keen about the gestures of his life.

Cavett says he is always mystified by McCarthyism. Hepburn says she gave a speech against it. And Spencer Tracy’s attitude? Cavett asks. He said to remember who shot Lincoln. You hope the kids who should watch these extraordinary interviews with the histrionic grandees of yesterday will remember that John Wilkes Booth was an actor.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in