The first play by the pioneering feminist Caryl Churchill has been revived at the Jermyn Street Theatre. Owners, originally staged in 1972, feels very different from Churchill’s later work and it recalls the apprentice efforts of Brecht who started out writing middle-class comedies tinged with satirical anger.

Churchill sets her play in the cut-throat London property market where prices are soaring and tenants are apt to be evicted if they can’t cover sudden rent rises. Marion is an estate agent who secretly buys a house occupied by her former lover Alec who is married to Lisa. Their third child is on the way. Marion hatches an evil plan to kick the family out and to claim Alec back as they sink into financial ruin. A secondary plot develops when Marion attempts to adopt Lisa’s new baby so that she can pass it on to her husband, Clegg, a psychotic butcher who longs for a son to inherit his business. This baffling and over-complex narrative is very carefully paced and the bizarre elements are set out in manageable pieces so that everything makes sense.

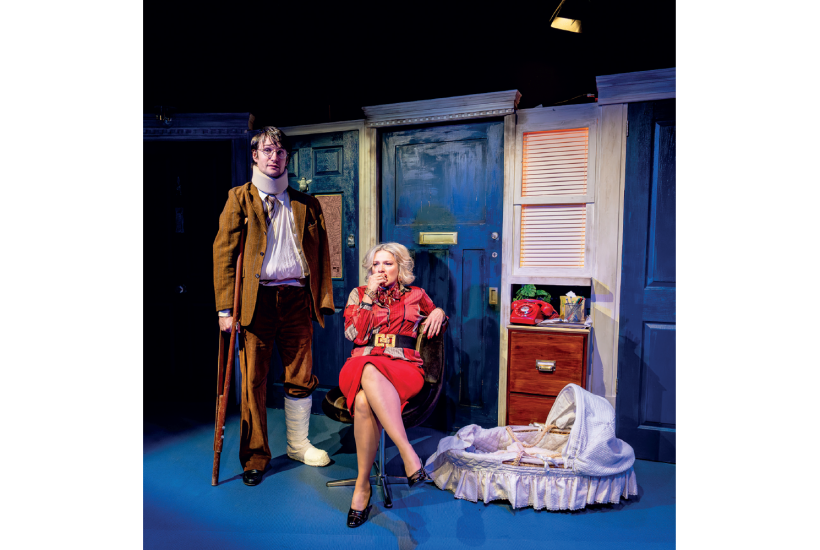

Offbeat comedy lubricates the moving parts. Marion employs a hopeless geek, Worsley, who longs to kill himself but keeps getting it wrong. He slashes his wrists and survives. He takes overdoses of pills without result. His many attempts to gas himself come to nothing. He spots an advert for the Samaritans and, misunderstanding the nature of their mission, asks them to send an adviser to facilitate his suicide. The mood of the piece is cruel, amoral and thrillingly macabre. Clegg, for example, plots to murder Marion by shooting her in the head or by starting a fire that may kill Alec, Lisa and their babies. No one raises any ethical objections to this plan. Lisa is raped by Clegg but she barley notices the moral niceties of their union because she’s preoccupied with keeping hold of Alec and her kids.

The characters bear a strong resemblance to the Cockney grotesques created by Joe Orton in the 1960s. And the quirky dialogue sounds like the sort of chitchat that Alan Bennett is always overhearing at bus stops. Clegg is jealous. He fears that Marion practises dancing with unknown male partners. ‘Dancing can be dangerous,’ he says, ‘and needs to be watched.’ When Lisa gets her face slapped she reacts by swearing violently, which Clegg finds offensive. ‘I don’t like to see a woman use language.’

Cat Fuller’s set features a row of nine front doors, squashed up shoulder to shoulder like a gang of thugs or a line of policemen. This surreal touch is not hard to interpret. Laura Doddington gives a whirlwind performance as the vicious and yet curiously likeable Marion, whose desire for children has been diverted into a crazed lust for Alec.

At the play’s close she delivers a visionary speech about empires being founded on heaps of blood-drenched corpses, but this is a rare deviation from the play’s central preoccupations. The themes it tackles are universal: love, greed, ambition, parenthood and families. Had Churchill continued to write in this accessible, crowd-pleasing vein she might have become as popular as Mike Leigh or Carla Lane (whose BBC sitcoms were watched by millions). Instead, she succumbed to the praise of crosspatch feminists who annexed her talent and ruined what they claimed to admire.

Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet about Shakespeare’s son who died in childhood has been lavishly adapted for the stage. The central character is Anne Hathaway, whose family name was Agnes not Anne. Apart from that, we learn no new information about her at all. The production is dominated by its sumptuous visuals. Every character, from the milkmaid to the forest urchin, is decked out in a brand-new costume tailored by the RSC. Since the setting is Stratford-upon-Avon, the actors speak with Ozzy Osbourne accents (although some don’t bother). The key location is Shakespeare’s newly refurbished kitchen-diner, a miraculous confection of honey-coloured joists that looks like a million-pound barn conversion. Alas, the show itself is a thumb-twiddling dud. The dramatist, Lolita Chakrabarti, defames Anne as a surly hysteric who wastes her time cooking, gossiping, preparing herbs, minding the sick and scolding the young. The emotional mood in her lovely kitchen is relentlessly sour. The women constantly swear, scream, slap and biff one another.

To avoid all this brutality Shakespeare wisely scoots off to London to make his fortune – although he pops back for Christmas and funerals. Anne has three children and each birth scene involves volcanic eruptions of petulant screaming. ‘I can’t do this,’ she bellows as her waters break yet again. ‘This is unreasonable.’ When Hamnet dies, Shakespeare collapses with grief but Anne isn’t convinced. ‘Where’s your despair?’ she yells in his face. The Bard beetles off to London, pronto. Who wouldn’t?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in