There is no question that the hordes of Woke lefties consider Australian Senator Jacinta Price to be just another ‘Uncle Tom’, for that is the disgraceful label they use on social media every chance they get. In their eyes, she exists to please and serve the white fellas – the coloured help, as it was distastefully put.

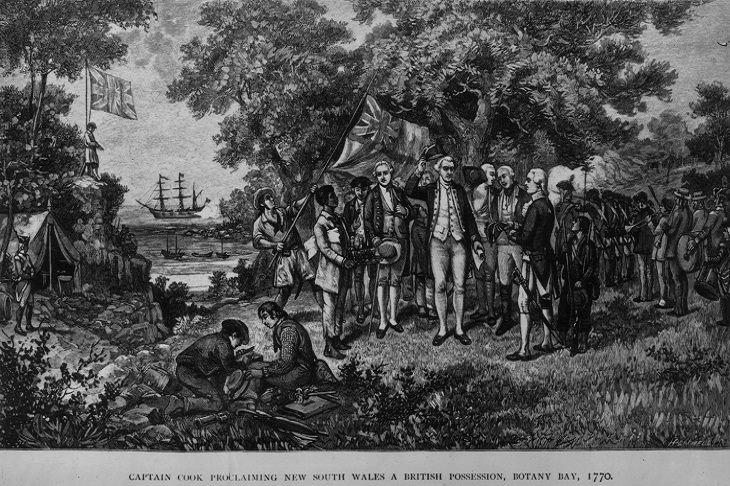

Following her National Press Club speech, the Northern Territory Senator caused a massive outcry by stating that colonialism has been good for Australia’s Indigenous population. The lefties went apoplectic about this of course – but that is to be expected. What she said was true and accurate, and her message needs to be heard.

In her 35-minute speech and the question time that followed, she passionately and rationally made her case against the Voice. As to her reply to a journalist from the Guardian who asked the question on colonialism, she said it actually had ‘a positive impact – absolutely’. She went on to say:

I mean, now we’ve got running water, we’ve got readily available food. Everything that my grandfather had when he was growing up because he first saw white fellows in his early adolescence, we now have. Otherwise he would have had to live off the land, provide for his family, and all those measures, which Aboriginal Australians, many of us, have the same opportunities as all other Australians in this country. And we certainly have probably one of the greatest systems around the world in terms of a democratic structure in comparison to other countries.

It is why migrants flock to Australia to call Australia home, because the opportunity that exists for all Australians. But if we keep telling Aboriginal people that they are victims, we are effectively removing their agency and giving them the expectation that someone else is responsible for their lives. That is the worst possible thing you can do to any human being, to tell them that they are a victim without agency. And that is what I refuse to do.

With this in mind, let me alert you to an important new book on the subject of colonialism. Oxford University ethicist and theologian Nigel Biggar recently released a book called Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023).

In it he seeks to make a balanced case for empire and colonialism. Unlike so many of the historical revisionists of recent times, he argues that at best there was a mixed track record. Colonialism was carried out with both good motives and bad motives, and the results were not all bad, as so many claim today.

Biggar’s volume primarily focuses on the record of the British Empire, so as can be expected, there is a fair amount of material on Australia.

There is, therefore, a more historically accurate, fairer, more positive story to be told about the British Empire than the anti-colonialists want us to hear. And the importance of that story is not just past but present, not just historical but political. What is at stake is not merely the pedantic truth about yesterday, but the self-perception and self-confidence of the British today, and the way they conduct themselves in the world tomorrow. What is also at stake, therefore, is the very integrity of the United Kingdom and the security of the West. That is why I have written this book.

He also puts his cards on the table as to where he is coming from:

I am a Christian by conviction and a theologian by profession, so my ethics are shaped, first and foremost, by Christian principles and tradition. That does not mean that readers who are not Christian need to find my moral views entirely alien. I am also a human being and I share a more or less common world with other humans. What is more, as a Christian I am inclined to believe that common world is structured by universal moral principles, and my study of ethics, both in the West and outside it, has confirmed that that is indeed so. For example, when, in 2013, I attended a conference on the ethics of war in Hong Kong, I discovered that ancient and medieval Confucian tradition had developed a concept of ‘just war’ that was very similar to the one developed in the Christian West – in spite of the fact that Chinese civilisation and Christendom had developed almost entirely independently of each other until the early modern period. What they had in common, they had not borrowed from each other.

My Christian ethical viewpoint can be characterised in two general senses as ‘realistic’. First, it involves the belief that there is an objective moral reality that precedes, frames and dignifies with significance all human choices: there are universal moral principles.

Second, in my ethical thinking I aspire to be honest about human limitations, about the enveloping fog that not infrequently blurs the sharpest eyes, about the inevitability of risk and about the relative intractability of historic legacy.

In some 480 pages of carefully argued and well-documented analysis, he makes it clear the anti-colonialist case is overstated and overly simplistic. The documentation is top notch, with over 130 pages of end-notes backing up the case he seeks to make. Consider briefly his discussion of the situation in Australia.

He spends a fair amount of time for example discussing the so-called Tasmanian genocide of the 1830-40s. He interacts with various scholars on this issue, and contends that the common definition of ‘genocide’ – the deliberate and systematic attempt by the state to eliminate a people – does not apply here. He does not whitewash what happened, and admits that the British were responsible for the inadvertent demise of the Aboriginals there. But he says that the British as a whole cannot be fairly blamed for what happened to them. He goes on to say this:

In North America, Australasia and Africa the policies of the imperial government in London, and consequently those of the colonial governments beneath it, were based on the Christian and Enlightenment conviction of the basic human equality of members of all races, and driven by the humanitarian desire to enable less advantaged – less privileged – peoples to survive, develop and flourish.

Biggar throughout seeks to offer us a balanced and fair assessment of British colonialism. In his concluding chapter he offers a list of ‘evils’ – both intentional and unintentional. And there were indeed some of these evils or injustices, be they slavery, economic disruptions, the spread of disease, and so on. He writes:

All these evils are lamentable, and where culpable, they merit moral condemnation. None of them, however, amounts to genocide in the proper sense of the concerted, intentional killing of all members of a people, the paradigm of which was the Nazi policy of implementing a ‘Final Solution’ to the ‘problem’ of the Jews. In the history of the British Empire, there was nothing morally equivalent to Nazi concentration or death camps, or the Soviet Gulag.

He also briefly discusses the issue of reparations, and the many problems associated with such a move. And given that a win on the referendum here in Australian would inevitably entail reparations, we need to be aware of the many drawbacks to it. However, he does go on to say that a case can be made for some modest reparations in some limited and particular cases.

Biggar finishes by offering a list of the benefits of colonialism, and his ‘credit’ column is lengthier that his ‘debit’ column. He reminds us that the British Empire – like all empires and all forms of human rule – did good as well as evil. While difficult to measure and calculate, a case can be made that British colonialism, overall, was not as bad as is so commonly asserted.

So much more can be said on the case he seeks to make. For those who want more on the book and its author, John Anderson recently held an hour-long video interview with him which you can see here.

Two closing quotes are worth offering here. In her Press Club speech Jacinta Price said this:

What has become abundantly clear is that when racial separatism that designates a class of Australians as another is prioritised over serving Australians on the basis of need we experienced failure. An industry has been established that provides opportunity for the already privileged to occupy positions that are supposed to deliver outcomes for our marginalized, based purely on the fact they share a racial heritage. My hope is that after October 14, after defeating this voice of division, we can bring accountability to existing structures, and we can get away from assuming in the city activists speak for all Aboriginals and back to focusing on the real issues – education, employment, economic participation and safety from violence and sexual assault.

And a very famous line uttered during another major debate about race relations fits in nicely here. Almost exactly sixty years ago Martin Luther King Jr. said this in his I Have A Dream speech which he delivered in Washington on August 28, 1963: ‘I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.’

And that is exactly why people like Jacinta Price, Warren Mundine, and so many others are fighting tooth and nail against the racist and divisive ‘Voice’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in