For nearly 50 years, the Scottish collection at Edinburgh’s National Galleries has been housed in a gloomy subterranean space beneath the main gallery, rarely visited, never celebrated. If you didn’t know it was there, don’t be ashamed. Just 19 per cent of visitors ventured into the bowels to find the jumble of Scottish paintings, dimly lit and hanging on colour-sucking, mucky green walls above a depressing brown carpet. Of those who did get there, lots immediately turned and fled back upstairs to the luminous comforts of Titian, Velazquez and Rubens. Safe to say, the space was not exactly showcasing Scottish art; a puzzling strategy for the country’s flagship gallery.

But no more. The underground space has been completely transformed and expanded, no mean architectural and engineering feat given the gallery lies in the middle of a Unesco World Heritage Site and sits above three railway tunnels feeding Waverley station. More than 130 works from the Scottish collection, dating from around 1800 to the second world war, now hang across a spectacular new exhibition space that is even larger than the original gallery above. Floor-to-ceiling picture windows frame views of Princes Street Gardens, the Scott Monument and Waverley, bringing natural light into the long exhibition space and offering a geographical prod to remind visitors where they are.

The collection is displayed in chronological order. If you start on the ground floor, you begin with the oldest pieces. A temporary display of David Allan’s irresistible ink portraits of Italian and Scottish characters fills the print room. Big hitters, such as Henry Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ (c.1795), hang beside the main collection while early 19th-century genre paintings get their own room on the way down to the new gallery, showing scenes from everyday life and historical events; marriage, industry, murder.

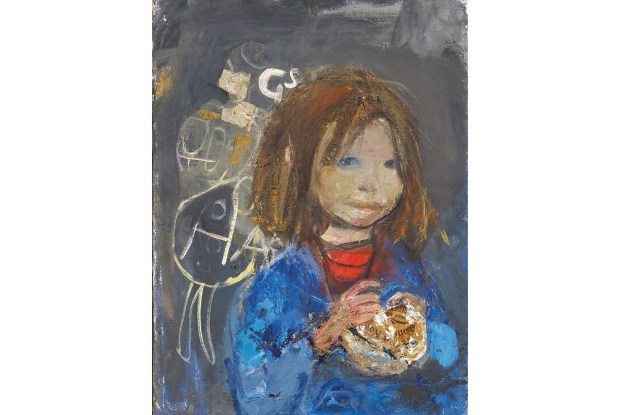

But most visitors will now enter from the Gardens and travel back in time through the Scottish collection before going upstairs to see the rest. ‘The Red Slippers’ (c.1942), a popular Anne Redpath, and one of the most modern work on display, looks into the foyer to tempt you in. Turns out it’s a double-sided painting. The reverse, ‘Borders Landscape’, faces into the gallery, and beside it there’s another Redpath, ‘Still Life with Milk Bottle’ (c.1945), an arrangement of greys, punctured by the sharp orange highlight of a Penguin paperback exiting stage left. It’s a confident start.

That confidence is everywhere. The hang is uncluttered. Each painting has room to breathe, and the viewer is never exhausted by the curse of too many paintings. The collection celebrates the style and technique of each artist, rather than getting too hung up on the social context in which they worked. You sense the gallery is, at last, proud of these works.

The vast new space is broken up into bays, each dedicated to a different theme. First come the pre-war years, where highlights include the in-yer-face jut of Alice Cowie, magisterial subject of her husband James’s portrait, ‘The Yellow Glove’ (1928), and ‘A Point in Time’ (c.1929/1937), the primordial reimagining of landscape by Borders abstract painter William Johnstone that gets a statement wall to itself. Works by less familiar artists are dotted throughout, including two by William McCance, one of the few Scottish painters to embrace the machine-age styles of the 1920s. McCance spent the first world war in jail as a conscientious objector, emerging to resume his painting and become an art critic for The Spectator, no less. One of his works is a portrait of his colleague, Joseph Brewer, then secretary to the editor, gleaming with the eerie uranium and arsenic greens of the 1920s, the other is ‘The Awakening’ (1925), an ambiguous contortion of seaside nudes.

Visitors are drawn down a long gallery of landscapes where William McTaggart’s ‘The Storm’ (1890) invites close inspection of the manic, fluttery brushwork. There’s more McTaggart later, too, his long career leaving the nation a huge stash of work that travels from mawkish Pre-Raphaelite girls to these startlingly modern semi-abstracted landscapes which, stripped of their figures, could have been painted 60 years later.

The shadow of the Pre-Raphaelites rears again in the woozy mysticism of their Celtic revival cousins. These decorative mash-ups of pagan folklore and Christian iconography divide the crowd, but the curators have assembled a collection to reward fans and challenge sceptics. John Duncan’s ‘Saint Bride’ (1913) looks fresh and spectacular (see below), its colours popping against the woad blue walls. The ornamental finesse of Phoebe Anna Traquair’s silk and gold thread embroidered panels (1895-1902) underlines her elite status in the arts and crafts movement.

A series of Edinburgh paintings is dominated by two large Alexander Nasmyths from 1825, portraits of the proud Enlightenment city teeming with life, commerce and construction. They flank a large window that reveals some of the same sights today. Any concerns about seeming too capital-centric have been set aside, and rightly. Edinburgh is one of the world’s great cities, it must be celebrated here. Glasgow is almost absent as a subject anyway.

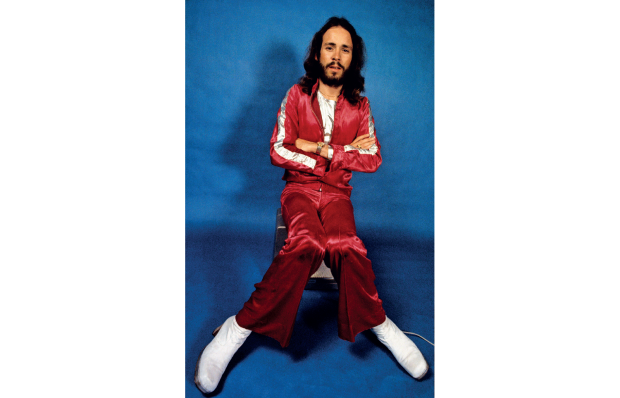

But Glasgow painters bound off the walls. The gallery wants the collection to be accessible in every way, so before rehanging they canvassed opinion on the nation’s favourite artists. They found, perhaps to their dismay, that Charles Rennie Mackintosh, an architect, topped the list. Maybe because nobody ever went to see the National Galleries’ Scottish collection. No matter, also name-checked were the Glasgow Boys and the colourists. These popular tastes are well served, with greatest hits including a Peploe still life, a J.D. Fergusson portrait and James Guthrie’s knife-wielding cabbage-patch kid, ‘A Hind’s Daughter’ (1883), defiantly dangling her severed greens in a muddy kailyard. Mackintosh fans will find one of his elegant watercolour landscapes in a temporary display of Glasgow Style works on paper that also includes pieces by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and Frances Macdonald MacNair, two of the strong female artists well represented across the exhibits.

As we venture deeper into history, storytelling replaces realism and decorative design, with once hugely popular Victorian artists drawing inspiration from literature, not life. The space fills with narrative works that present scenes from Shakespeare and Dante, converse with the mythical poet Ossian or even translate the 15th-century verse of King James I into an elaborate and immaculately restored four-part folding screen. This is ‘The King’s Quair’ (1867-68) by William Bell Scott, a largely forgotten artist poised for a renaissance.

As the collection nears its end, Henry Raeburn’s great portrait of Sir Walter Scott (1822-23) signals that the fictions are starting to blur with reality. Scott is pulling the strings in this final space, encircled by paintings that transpose his vision of an imagined Scotland on to real landscapes. Not many Scots read his work today, but we all recognise his world. Extravagant interpretations of Highland and Lowland landscapes, misty glens and awe-inspiring mountains conjure a familiar romantic Scottish reverie that has, for all its critics, endured to the present day. And, of course, at the end of the room, surveying these worlds with an imperious eye, stands ‘The Monarch of the Glen’ (c.1851), the omnipresent Scottish symbol, painted by Edwin Landseer, an Englishman.

The gallery is unapologetic about showing off this work, which is either the first or the last thing a visitor to the new space sees. Texts acknowledge that these paintings represent an idealised version of Scott’s ‘land of the mountain and the flood’; Horatio McCulloch’s ‘Highland Landscape with a Waterfall’ (c.1835) is probably imaginary, other landscapes have been dramatically sexed up. Raeburn’s portrait of ‘Colonel Alastair Ranaldson Macdonell of Glengarry’ (c.1812), inspiration for a tragic chieftain character in Scott’s Waverley, presents him as a dashing hero, not the architect of brutal land clearances.

It’s a partial and heavily edited shortbread shorthand for a complex modern country. But the stag, the misty landscapes and the tartan remain sensationally popular. Nearly 200 years on from Scott’s death, his conjured country is still the Scotland that sells, and the National Galleries, in thrall to no agenda beyond proudly sharing its art, isn’t ashamed to admit it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in