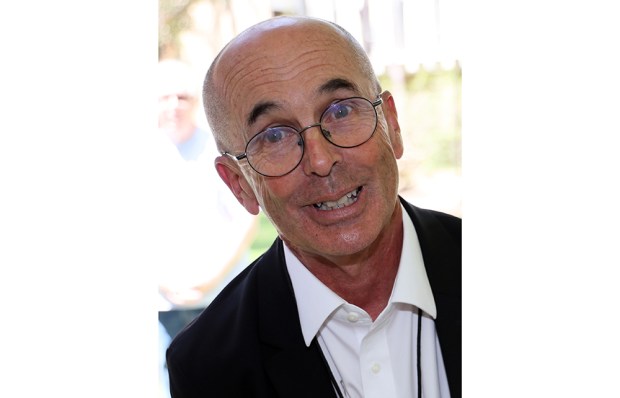

Oh Ed, Ed, Ed, Ed. You have written a magnificent tome, but I am so conflicted about it. Party Lines is more than 400 pages: a quote from Goethe at the start, a lengthy introduction, plus a glossary and an index. But we get into semantics from the beginning. What is dance music now? Practically anything with a beat that isn’t George Ezra or Sam Fender – and they’ve probably got a load of dance mixes on the go as well.

This is not a definitive book about dance music. There is, for example, scant mention of the late and supremely influential Andrew Weatherall, chief architect of acid house and the scene that followed. Yet Spiral Tribe – a very agreeable bunch of travellers who happily gave me their vinyl music to play on my BBC radio show – get pages of attention.

I think it would have been far better to include the word ‘underground’ in the title, and also ‘politics’. Ed Gillett admits early on that there have been several excellent books written about the modern music revolution – a view with which I concur, arms in the air (like I just don’t care), Simon Reynolds’s Energy Flash and Matthew Collin’s Altered State among them. Gillett worked on the breathtaking 2018 Jeremy Deller film Everybody in the House – An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992. That started with the miners’ strike and included conflicts from then on. Perhaps Gillett wanted to complete the incomplete film with this book.

He and Deller are prophetic, reflecting worrying reports coming now from the world of British rap and drill that their lyrics are being used and scrutinised by the authorities to prosecute them. The thrust of this book, therefore, is not about dance music per se. It’s about the power of politics to try to stop it. Which may lead some back to blues and protest songs of yore, as well as the days of Buffalo Springfield’s ‘For What its Worth’ NWA’s ‘Fuck Tha Police’ and Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ – just a few of a myriad of anti-police protest genres, not used much as evidence for prosecution, as far as I am aware, by the LAPD. So things haven’t improved on the whoo-hoo music and the police front at all.

Party Lines is not largely about the hedonism which accompanied the glory of late 1980s and early 1990s acid house, techno and rave. It’s about those who exploited it; and if they couldn’t, tried to stop it; and if they couldn’t stop it, would damn well make money out of it. It was the brewers who lobbied parliament because young clubbers had forsaken lager for a bottle of water and a pill in a field.

The book goes into such infinitesimal detail about political acts, covering and linking the proto-raves of the 1970s travellers onwards, it’s like a sort of rave Hansard. Gillett says at one point that he discovered this music in his father’s CD collection in the 1990s, and that he was born in the mid- 1980s – which means that he was too young to have encountered many of the live experiences he references.

Yes, well, I meet a lot of people who say ‘I wish I’d been around in the 1990s’. The music was terrific. The young were able to feel that they were, however ephemerally, able to change society. They were challenging authority, and having a good time as well, to an exhilarating soundtrack. It’s that exuberance which is missing from Gillett’s book.

One can hardly blame the author for being born a bit too late. But this is a historical exercise painstakingly put together, referenced, indexed and explained without the joie de vivre of the era. There is no sense of glee, of the sheer abandon of dancing to a dodgy sound system out of doors at dawn somewhere you shouldn’t be with a glorious mélange of loved-up roofers and first-year trainee surveyors.

Yes, the police have always wanted to prevent young people having a good time, and attempted to restrict them. I had personal experience of ‘kettling’ when trying to put on a party in central London on the day of – ha ha, how Establishment! – my investiture at Buckingham Palace. It happened to be 1 May, the up-till-then annual day of protest. The Met were out in force corralling, and holding my guests who had popped their heads out of the door to see what was happening. Kettled for being curious.

Good for Gillett for going to so much trouble to chronicle the ludicrous attempt by parliament to ban repetitive beats. But he has missed the joy of a generation being able to break out of the shackles of conformity. One seaside rave I went to in Brighton was attended by several on-duty coppers. It was 5 a.m. One of them said that at the end of his shift he was going home to change into something more casual, then coming back to join in the rave. I really don’t think he was an agent provocateur in the making.

Gillett is surely old enough to have got into what remained of rave culture from the end of the 1990s onwards. There were plenty of unlicensed raves happening even in lockdown, from Blackburn to Primrose Hill. He has amassed a huge amount of information, for which I have nothing but admiration, but, oh my days, I think we need to take him out for a pint.

Party Lines will be essential reading for those studying British social history in the late 20th and early 21st century. But a more colourful tone would have been welcomed, and more connection with the reader. I have great belief that the oppressed underground culture will always find a way to spring up again from the cracks in the paving stones. Look out, listen up for phonk. Go for it, Ed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in