Manchester is desperate for workers. There are 40,000 jobs advertised in the city at the moment, at every pay grade. Ann Summers wants a stockroom assistant (£10.70 an hour), or you could invigilate exams at £14 an hour or post videos on TikTok for £20 an hour. Sellcheck Chemicals is offering up to £75,000 a year for a sales manager (‘No biology background needed, no previous experience necessary’). Even the army is offering trainee officers £34,000 after their first year. But ask any employer in the city what it’s like hiring and they’ll tell you: it’s a battle.

What’s strange about this is the fact that though all these jobs are on offer, unemployed Mancunians don’t seem to want them. Figures published last week show that 18 per cent of Manchester’s adults are claiming out-of-work benefits. Some 120,000 have reported as long-term sick. Welfare dysfunction has created a huge hole in the workforce.

It’s the same story in city after city. Somehow, the UK has managed to combine mass joblessness with a worker shortage. Almost one in five working-age people in Birmingham are on out-of-work benefits, and it’s the same story in Glasgow and Liverpool. In Blackpool, the number is closer to one in four. This is a huge waste of lives, leaving aside the issue of taxpayers’ money.

Though Rishi Sunak promises welfare reform, it’s not clear how he intends to deal with a problem of this size. His officials have warned him that things are set to get much worse. There are 5,000 claims per day for sickness benefits, many on the grounds of poor mental health – almost twice the

pre-pandemic rate. No one expects that rate to start slowing. Internal government forecasts now envisage the welfare caseload rising for five years, with the number on disability benefits surging by a third to 3.7 million. The Prime Minister’s officials are admitting that we won’t escape this trap any time soon.

So who will fill the million-plus vacancies? How can we grow the economy? The answer to this question will become clear next week, when figures are released showing that mass immigration is back on a scale that would have been unimaginable not so long ago. And rather than treating it as a problem, Sunak’s government seems to regard it as a solution to Britain’s missing workers.

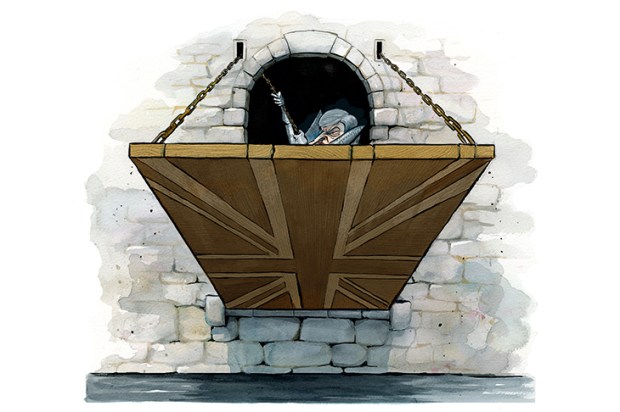

During the Brexit campaign, much fuss was made of the news that immigration had hit 323,000 a year, making a mockery of David Cameron’s promise to reduce it to the ‘tens of thousands’. Brexiteers and Remainers alike assumed the whole point of leaving the EU and ending ‘free movement’ was to reduce arrivals. The consensus was that about 130,000 a year was right. We now take that amount of people roughly every ten weeks. The net migration figure released next week is expected to come in at above 700,000 a year: by far the largest in the history of our islands.

While it’s true that next week’s numbers will be inflated by refugees from Ukraine and Hong Kong, and by students (many of whom arrive with dependants in tow), the underlying trend is clear. The Office for Budget Responsibility has abandoned any idea that Brexit meant cutting back immigration, because there is no evidence that anyone in government is remotely serious about doing so. It now forecasts, long-term, around 250,000 arrivals a year – almost twice the post-Brexit projections. A second great wave of migration has begun.

While the first wave of mass immigration in recent decades was an unforeseen consequence of expanding the European Union, this one is planned. The Tories have taken back control and used it to ramp up immigration to a level that New Labour would never have dared attempt.

It’s often said that the United Kingdom is an immigrant country. This is not quite true. Until the mid-1980s, we were a net exporter of human beings. In 1948, parliament passed a law giving all 800 million citizens of the Commonwealth the right to live and work in Britain, the assumption being that hardly anyone would want to come to these rain-battered islands. Waves of migration made the news, but they barely dented the demographics. When more people started to arrive in the 1990s, the numbers were modest. So the EU’s borderless future was designed at a time when no one imagined the level of mass migration to come, because it had never happened before. Tony Blair had no idea that he was about to preside over a new economic model. He didn’t plan for it, because he just didn’t see it coming.

The problems are becoming obvious. The mass movement of migrants meant that employers preferred cheaper, foreign-born workers over investing in training locals. The consequent increased pressure on housing, schools and hospitals are what led, in part, to the Brexit vote. People wanted their politicians to make a better job of managing globalisation.

Boris Johnson talked about controlling migration to force companies to pay decent salaries: if that meant higher prices, so be it. He saw the national shortage of truck drivers as a wake-up call: such people should be valued and paid properly. This wasn’t just Brexiteer bravado. Sir Stuart Rose, the ex-M&S chairman and a Remain campaign chief, argued the same: the end of free movement would push up wages for low-skilled workers, he said – though he thought this was ‘not necessarily a good thing’. Both sides agreed Brexit would mean lower migration and higher salaries. Not many would make that case now. Rather than rising, real-term incomes are midway through their sharpest fall since postwar records began.

A milestone was passed this week when it emerged that 20 per cent of the UK workforce is foreign-born – making us more of an immigrant country than even the United States. Brexit has brought in a different mix of migrants. India has supplanted Poland as the biggest source country for new workers: followed by the Philippines, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Australia and the United States. Interestingly, post-Covid sickness and mental health issues haven’t seemed to afflict Britain’s immigrant community in the same way as they have its natives.

But while the US regards itself proudly as an immigration nation, our Prime Minister’s strategy is to act as if nothing is happening. There is no Statue of Liberty at Victoria Coach Station in London, though a quarter of all UK schoolchildren have an immigrant mother. In London it’s just over half.

Brexit Britain can claim to be one of the most welcoming countries in the world with a work visa approval rate of about 96 per cent. It’s almost 100 per cent for Americans (12,382 applied and just 47 were refused). Non-EU citizens are no longer treated as second class: in fact someone from Kyrgyzstan is more likely to get a work visa than someone from Germany. Before Brexit, just seven people from Tajikistan were granted visas a year. Now, it’s about seven a day. Visas for people from India have doubled since the Brexit vote. Zimbabwe is up 20-fold, Uzbekistan 100-fold.

Britain is now the country where workers of the world unite. So far, all this is being done with success and harmony that would astonish the rest of the world. There is virtually no anti-migrant backlash: indeed, a recent poll showed Britain to be one of the most pro-immigrant countries in the world. We’re also about the only country in Europe not to have a serious anti-immigrant populist party in parliament or with any significant showing in the opinion polls. Concern about migration is far lower than it was pre-Brexit, even if the numbers are higher, which is in part because the government has taken control of who arrives.

To enter Britain there is a list of conditions: you need to be an English speaker with a sponsor, a job offer and a minimum salary, and in an approved profession. Perhaps this has made the influx less controversial – it’s immigration but with greater democratic consent. But it’s also easy to see how this could begin to sour. We still need many more workers and they will all keep coming. There will be ever more pressure on hospitals and schools. This is the problem Sunak faces now. How to address the problems that mass migration brings, without seeming to have betrayed Brexit?

Perhaps every new worker is vital to the economy but the fact remains that the government is issuing visas equivalent to a city the size of Southampton every year – and there are certainly no plans to build a new Southampton every year. He needs to ask: where will the newcomers live? Who will build their houses, teach their children, tend to their sick? To dodge these questions, to pretend it’s not all happening, guarantees big problems in the future.

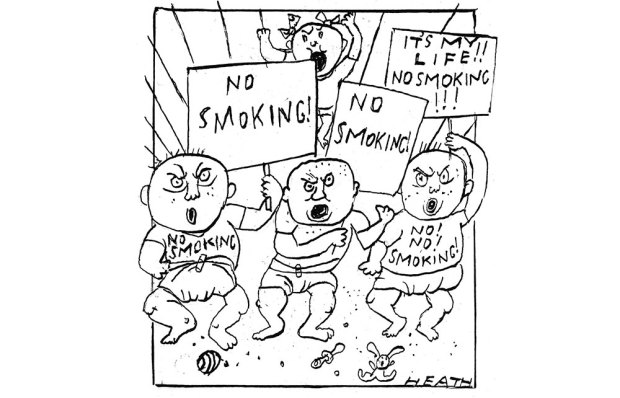

Being honest about mass migration also means being honest about the trajectory of British welfare. Yes, Sunak would like reform. But if his own officials are predicting a massive increase in mental health caseloads, on the assumption that the problem is going to get far worse, then it’s time to talk about this too. Why do we think a million more people are going to end up on disability benefits? Why in Britain, not anywhere else? The reason this question is so difficult to discuss is that tough-love welfare reform is fraught with political danger. No politician wants to be accused of being heartless.

Politically, it’s easier to write the cheque and forget about the long-term sick. It’s astonishingly easy to do so. When figures were released this week showing 5.3 million on out-of-work benefits, up from 5.2 million – already a staggering figure – it was given no coverage at all. It’s amazing how recategorisation of benefits can make millions disappear: politically, at least.

Sunak embodies the quiet success of British integration, but there’s a risk in getting too carried away. The industrious Zimbabwean and Australian immigrants can hardly be blamed for welfare dysfunction. But if they are being used to cover it up, then it’s worth discussing.

Is it possible to give up on welfare reform and use mass immigration to build post-Brexit Britain? Absolutely. Is it desirable? That’s another question. And it’s one the Prime Minister should really get around to answering before too long.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in