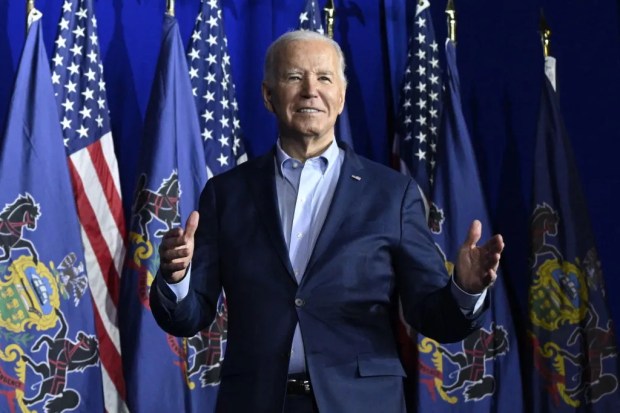

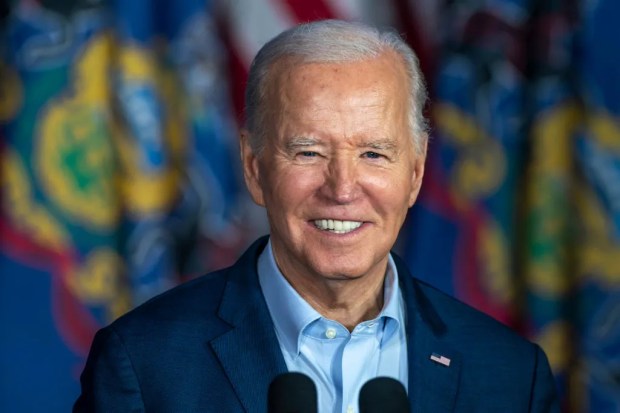

For the British government, the Biden visit to Belfast posed one major exam question: would the pageantry of a pan-nationalist juggernaut rolling into town, led by the most tribally Irish-American President of all time, make it appreciably harder for the DUP to accept the Windsor Framework and so to re-establish the Stormont Executive as the cornerstone of the Good Friday Agreement? For as it stands, Rishi Sunak’s mission to stabilise the Union in all its constituent parts is not yet complete.

Every moment of the US President’s brief time in the province had to be evaluated according to that exacting yardstick. Tin-eared locational and linguistic symbolism risked raising the hackles of unionist ‘Middle Ulster’, otherwise known as the proverbial ‘Prod in the garden centre’.

The visit also had the risk of fuelling communal excitability at a time when the dissident republican threat is growing again and with another potentially divisive election next month. The local media’s rather self-regarding yearning for poetry infused soliloquy (their own as much as the President’s), was a secondary concern. Not everyone needs to live through the excitement of 1998 all over again.

The historical memory at the top of the British government was thus strong enough to prevent a repetition of the imbalance of the last of Bill Clinton’s visits to Northern Ireland as President in 2000.

Clinton’s valedictory tour contrasted markedly with the political discipline he showed on his first two trips in 1995 and 1998 when he accorded both unionist and nationalist communities ‘parity of esteem’ in both his public pronouncements and in the aesthetics of the sites he visited.

In 2000, the British government under Tony Blair did not push back strongly enough at the White House when the final visit to both the Republic and Northern Ireland was being organised — because they felt they could not deny Clinton his lap of honour as his days in the White House came to a close.

Clinton badly wanted the IRA decommissioning weapons as his crowning achievement in the affairs of Ireland and to that end felt he had to nudge Sinn Fein gently (so gently, as it turned out, that they delivered nothing to him in the end: the act of decommissioning was finally done under the Presidency of George W Bush, who had done almost nothing for Irish nationalism but led an America that had been shaken out of lazy complacency about the reality of terrorism).

The Biden visit to Northern Ireland this week was far more at the 1995 and 1998 end of the scale. The main lesson of the visit is that the weight of the British state — still the key player in the Ulster crisis — counted for something both domestically and on the international stage. And if the institutions get back up and running again in the next few months, those who quietly steered the Presidential visit towards respect for the sensitivities of Northern Ireland will have earned their place in the history of Anglo-American diplomatic relations.

Despite the ‘noises off’ from Capitol Hill calling for a more ethnocentric approach, both the White House and State department professionals acted in the spirit of Senator George Mitchell, the chairman of the all-party talks, rather than Rita O’Hare, Sinn Fein’s former Washington DC representative.

In contrast to former speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and the voluble Congressman Richie Neal of Massachusetts, the foreign policy establishment knows that in international law the US is not a guarantor of the Good Friday Agreement. This awareness was further exemplified by Presidential envoy to Northern Ireland, Joe Kennedy III, sticking to his economic brief and not straying into politics in the run up to Biden’s visit.

The day’s proceedings reminded that Ulster has an ability to generate its own controversies that cut across the finest of diplomatic niceties. First, the Presidential visit was preceded by republican rather than loyalist low-gradery on the streets of Northern Ireland in the form of rioting in Londonderry by pro-dissident elements. For once, given its habit for self-defeating rage, Unionism was therefore not placed on the moral defensive.

Second, the claim by former First Minister Arlene Foster on her GB News show that Biden was anti-British led to the Biden team denying that the Commander-in-Chief was Anglophobic. Indeed, his English forebears were montaged to even up the ethnic score.

At one level, it was all fairly meaningless; but the mere fact that the Biden administration had to genuflect in this way was significant. Again, this was recognition by the US administration that it takes two (communities) to tango.

The choice of venue for Biden’s big set piece speech, at the new University of Ulster campus, was in the impeccably neutral Belfast city centre (as so often, another Northern Ireland grand projet paid for by the British taxpayer: the reality of US investment has always lagged behind the extravagant hopes and even promises).

Significantly, Sunak did not join Biden for this speech — just as Major and Blair largely left Clinton to his own devices. It later transpired, only because he was spotted by a member of the public, that Sunak had made the journey to pay a very discreet visit to the officer shot in Omagh, Co Tyrone, recently by republican dissidents whilst coaching a youth football team.

It was of a piece with Sunak’s message last Saturday, quoted on the front of the News Letter, the main unionist daily in the province, tipping his hat to the role of the security forces in bringing about the peace process. All this points to a long overdue willingness of the government to challenge the predominance of Irish Republican narratives on both sides of the border, which hold that the campaign of ‘armed struggle’ during the Troubles was unavoidable. Again, the struggle for the past is critical to the communal mood — and thus for the willingness of the DUP to agree to the restoration of Stormont.

The only wild card now might be Biden’s verbal indiscipline on the southern leg of his visit to the island of Ireland: senior figures recall that even Tony Blair’s team was utterly unsighted on the optics of Clinton’s final visit to the Republic in 2000.

But at least Biden’s semi-comedic conflation of the All Blacks with the Black and Tans concerned events sufficiently in the past as not to be offensive. The chances of a conscious atrocity, after the fashion of Charles de Gaulle’s infamous ‘Vive Le Quebec Libre’ speech at Montreal City Hall in 1967 — which gave a powerful boost to Quebecois separatism — seem to be diminishing.

How did this relatively benign result come about? Partly, it is because — as Biden publicly acknowledged in Belfast — the UK government and the EU both made compromises under the Windsor Framework.

At a purely personal level, Sunak is now a regular interlocutor with the US President, whether at the AUKUS summit in San Diego alongside the Australian Prime Minister, or at next month’s G7 meeting. And he is not in a massive hurry to strike a ‘full fat’ Free Trade Agreement with the US. It invalidates the assertion of elements of the Irish-American lobby on Capitol Hill that Northern Ireland policy constitutes a major point of American leverage over the UK.

But there are longer term geopolitical considerations at play. The US could afford its indulgence of Irish nationalism during the Clinton years because the world was a less dangerous place in the immediate post-Cold War era; America was the world’s sole superpower, by a country mile. Not so now.

America needs real allies again. Put simply, the UK is an infinitely more important partner for the US in maintaining world stability than the still neutral Republic of Ireland — as President Zelensky, for one, is well aware.

The UK’s population is 13 times that of the Irish Republic and its economy is the world’s sixth largest; its armed forces are amongst the best in the world and one of the few that are interoperable with those of the US; it has an independent nuclear deterrent, is a key player in the Five Eyes and has the status of a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Crucially, the grand strategic choice made by this government has been to cease any hint of hedging on the China question after the fashion of other key principal allies of the US — notably President Macron’s recent performance in Beijing. Yet in the affairs of the island of Ireland — not least in Washington DC — the UK system has too often acted as if it is a nation the size of Norway or Denmark.

Rishi Sunak has shown with the Windsor Framework, and now with the Biden visit, that it is more than possible to win back lost ground. But will the DUP appreciate any of this? And will unionist voters notice the DUP grumpiness — and might they punish them for their slow, grinding indecision, as they gracelessly slither back into Stormont but gain no political kudos with the wider UK in the process?

The DUP knows it is being challenged on both flanks — from the right, by the purist TUV, and from the left by the Alliance party (an increasingly neutralist bloc which is nonetheless attracting disillusioned middle-class unionists). Its results in the 2019 general election illustrated the point, not least in Sir Jeffrey Donaldson’s own seat of Lagan Valley, a once solidly orange seat now under pressure.

As so often in Northern Ireland politics, it’s a narrow ground to traverse. Unionist voters have tended to punish Unionist parties that cannot maintain a relationship with UK governments — albeit not at any price. Nobody is suggesting that ‘any price’ was paid here; the talk in the DUP is all of the Windsor Framework being ‘oversold’, not of a betrayal after the fashion of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement.

That is why patience at the highest levels of the UK government is not fully exhausted but close to being so. A UK Prime Minister went into bat for unionism with the UK’s most important ally. The US responded in a fashion not often seen from a superpower. Can unionism’s elected representatives now respond in kind?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in