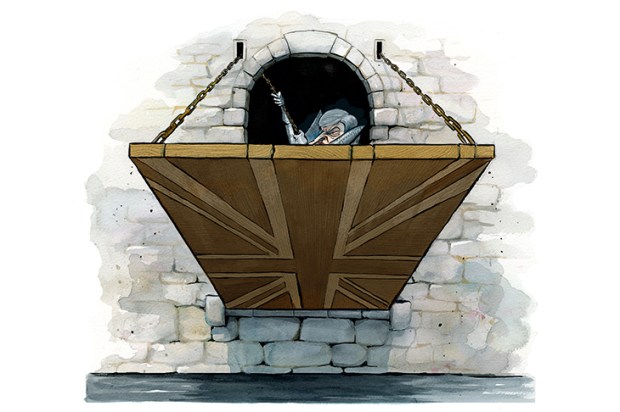

The parable of Liz Truss is, by now, world famous. A free-market idealogue was elected leader by the radical wing of her party, then trashed the economy by enacting her deficit-financed tax cuts. She invoked Hayek and Thatcher and was cheered on by their admirers. But her mini-Budget terrified the market and she had to quit – after doubling everyone’s mortgage rates. In the end, it was not the experts she was rebelling against, but economic reality. She had applied 1980s economics to the 2020s and it had ended in disaster, for her and for her country.

As prime minister, Truss was stunned by the potency of this narrative. Not only the IMF but Joe Biden weighed in to criticise her for reasons she considered demonstrable nonsense. She was hardly cutting any taxes: just a penny from income tax and reversing the fairly recent National Insurance hike. There was also a cut for the very highest earners, which cost very little. But her mini–Budget was, in most part, a borrow-and-spend extravaganza to subsidise fuel bills for every household in the land. How can this be twisted into a narrative that tax cuts don’t work?

When Katy Balls and I meet her in her new office in Portcullis House to record an interview for Spectator TV, she says she believes enough time has passed to talk plainlyabout her 49-day premiership and disentangle what went wrong. Her hopes of being a lean tax-cutter, she says, were flattened upon her arrival in No. 10 by the global energy price surge – leading most governments in the world to start huge bailouts for terrified consumers. Truss ended up making her mini-Budget into one of the biggest borrow-and-spend splurges in UK history. She justifies it nonetheless.

‘As soon as I got into office, we had an immediate issue of energy bills,’ she says. ‘People were anticipating energy bills of up to £6,000 that winter. We had a lot of businesses that could potentially go out of business because of the scale of the expected energy price spike, and we knew we had to act before the bills went out in October – otherwise we would have had a very serious winter crisis.’ The £6,000 forecasts turned out to be a scare: the real figure, we now know, would have been closer to £4,000, even without any subsidy. But at the time, her fuel bill bailout was costed at £60 billion.

And where would she get that money? From the debt markets, which had just started a global rebellion against borrow-and-spend governments. From New Zealand to New Mexico, mortgage rates had surged in the weeks leading up to her mini-Budget. This caused agony everywhere – but Britain’s borrowing rates spiked more than any other country’s. Truss doesn’t dispute estimates that only half the UK rise was down to global factors. But the UK part, she says, was not all down to her.

‘I believe there were other factors apart from the mini-Budget,’ she says. ‘The key thing we didn’t know about was the LDI issue’– the so-called ‘liability-driven investments’ used by UK pension funds, which she says she found out about only later. Some £1.6 trillion of assets were tied up in those funds, a staggering 60 per cent of GDP. Quite a domino to fall. A subsequent investigation found that regulators had only stress-tested LDIs to a scenario where borrowing rates rose one percentage point over a short period of time.

The day before her mini-Budget, ten-year borrowing rates had risen to 3.5 per cent, up from 2.5 per cent a month earlier: into the danger zone. No one in the Bank of England, Treasury or No. 10 had realised, so no one warned her. ‘If we’d known that beforehand,’ Truss says, ‘we certainly would have maybe moved the mini-Budget. Or waited a few days, to see what happened.’

Within a few days, a panicked Bank of England was offering a £65 billion bailout fund to save the LDIs. All this at a time when a new PM was talking about borrowing staggering sums from the markets for a mixture of splurge and tax cuts, while telling the Office for Budget Responsibility not to bother doing the sums. Her strategy would have been highly risky in normal times. But on top of an LDI crisis that looked set to repeat the subprime crisis of 2007, it was just too much.

As rates kept soaring, Truss says she was told by senior Whitehall officials that she would sink the UK economy unless she rowed back on her tax cuts. ‘I wanted to make sure that the markets were stable,’ she said. She also needed to signal a change. Kwasi Kwarteng, her chancellor, had been in Washington angrily denying that he would u-turn on any of the measures. Knowing Kwarteng would never agree to the full-scale retreat, she fired him. ‘I weighed it up in my mind about whether I needed to do that. But the reality was that I couldn’t, in all conscience, risk that situation,’ she says. ‘I was getting some very serious warnings from senior officials that there could be a potential market meltdown the following week if I didn’t take action. I needed to do as much as I could to indicate that things were different. And that’s why I took the decision I did.’

Tax cuts and chancellor went. To the world, this looked like a Truss-induced crisis. ‘The vast majority of the mini-Budget was the energy package,’ she says, not ‘un-funded tax cuts’. ‘The other measures were fairly small, in the general scheme of things.’

One of those ‘fairly small’ things was cutting the top rate of tax from 48 per cent to 42 per cent: a huge boon to the highest-paid, during a cost-of-living crisis. Did she realise that, whatever its size ‘in the general scheme of things’, this was a politically huge decision? ‘We wanted to attract people to the United Kingdom. We wanted to attract business… perhaps I underestimated the political impact it had.’

Her plan, now, is to keep making the case for tax cuts, and join what she regards as a battle of ideas in the Conservative party. ‘I definitely want to be part of promoting a pro-growth agenda. I definitely want to carry on as an MP,’ she says. ‘I think we need to start building more of a strong intellectual base. But I’m not desperate to get back into No. 10.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in