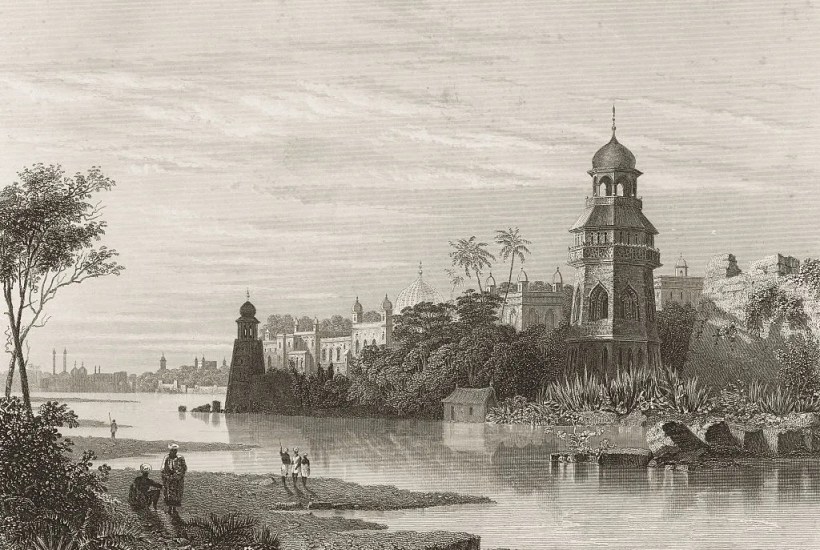

In India, a generation has been brought up on the academic Edward Said’s unhistorical prejudices towards the British and what he called the ‘colonial gaze’. In his eyes, British Orientalists were guilty of what is now termed ‘cultural appropriation’.

To his followers it therefore may come as a surprise to learn that it was British Orientalists who in fact rediscovered India’s classical history and heritage and made it available to the rest of the world.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in