There are various staples of still life painting, some symbolic, some not. Skulls and musical instruments suggest the transience of human pleasure; crocks and bottles are usually just vehicles for displays of technical virtuosity. Crocks and bottles are what Giorgio Morandi painted, not because he wanted to show off but because he liked their lack of symbolism. So it’s odd to find a still life of musical instruments in the Estorick’s new Morandi exhibition.

The habitual axis of Morandi’s still lifes is vertical, but the dingy brown trumpet, mandolin and guitar in this composition lie in a heap as if too bored to exert themselves. The picture strikes a bum note. The subject, it turns out, was imposed on him, a commission from a new patron he was eager to please. Luigi Magnani would go on to acquire 50 more works by the artist, all currently on loan to this exhibition while the Magnani-Rocca Foundation is closed for the winter. A musicologist, Magnani even supplied the artist with a set of valuable instruments to paint. Morandi couldn’t do a thing with them. On collecting the finished work in 1941, Magnani was surprised to find his precious antiques replaced with toys picked up in a flea market. He never made the same mistake again.

Morandi could only work with cast-offs: bottles, flasks, bowls, pitchers, old Ovaltine tins, objects, one critic said, that ‘should have been thrown out long ago’. Instead, they found refuge in his bedroom-studio ranged on three still-life tables of different heights or crowded on to the floor beneath. The maid who cleaned the flat he shared with his three unmarried sisters on Bologna’s Via Fondazza was under strict instructions not to touch them; while the rest of the tiled floor was polished to a shine, they gathered dust.

A mannequin in an early ‘Metaphysical Still Life’ of 1918 betrays the influence of Giorgio de Chirico he would later deny. The aim of pittura metafisica, as de Chirico saw it, was ‘to see the ordinary in an extraordinary way’ but Morandi found the ordinary quite interesting enough without lumbering it with metaphysical meanings. From the domestic objects arranged in rows or huddled on his tabletops he created miniature skylines, built environments he could contemplate from bed. ‘Even a still life is architecture,’ he said.

He painted in the afternoons in natural light from the window on to the garden; variations in colour and tone are as subtle as whispers, but the mood music changes. ln one of a pair of tannin-coloured wartime still lifes of 1942 the bottles, jugs and tins stand to attention, all present and correct; in the other they slouch at their posts, bending their necks as if to look outside the frame. There are no illusions of transparency or reflection in his still lifes, and few shadows – no meretricious academic tricks. As if to save himself from temptation Morandi filled his bottles with pigment, covered his copper water pitchers in matte paint and emblazoned his tins with ovals and rectangles. They were painted twice over.

Magnani first discovered his work in Rome in the third Quadrenniale exhibition of 1939 organised under fascist government sponsorship. In later life Morandi liked to pretend that fascism had passed him by as ‘a simple provincial professor of etching at the fine arts academy of Bologna’, but the truth was that he owed that professorship and his inclusion in official exhibitions to his connections with fascist intellectuals. Like many Italian writers and artists, he had initially welcomed fascism as a new broom that would sweep away the ‘passatismo’ of the conservative art establishment; when informed of the 1922 March on Rome by a waiter at his regular bar in Bologna, he held his nose and sighed. Disillusion eventually set in. When the Allies bombed Bologna in 1943, he left his still-life objects in his studio and, equipped with a special permit from the military authorities, painted landscapes around Grizzana, the village outside Bologna where he often spent summers. In one, a farmhouse is engulfed in jagged vegetation; by 1944 the village was a battleground. When Morandi’s house was looted by German soldiers billeted there, he was pleased they hadn’t thought his paintings worth stealing.

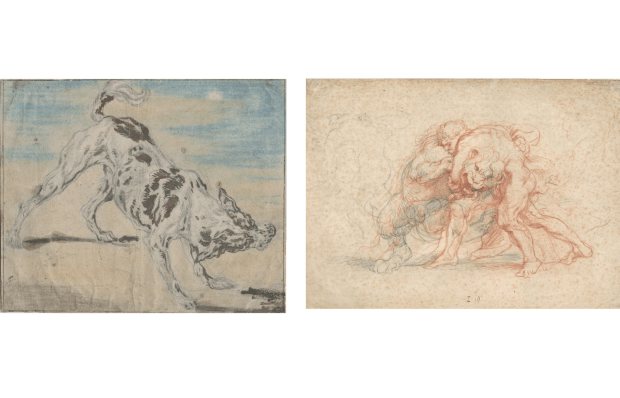

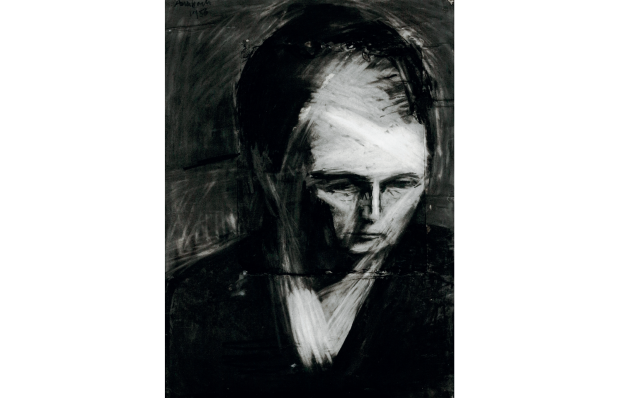

Morandi was self-taught as a printmaker and his etching technique is quite distinctive (see above). His dense cross-hatching casts a gauzy film over things, making them appear as if through mists of memory; it lends a shimmer like a heat haze to ‘Haystack in Grizzana’ (1929), which almost seems to exhale the scent of hay. His empty landscapes always feel inhabited, just as his still lifes breathe a human presence. The late watercolours and drawings of the 1960s barely touch the paper – to say they are understated would be an understatement – but they still feel lived-in. Other artists’ still lifes may be showier, but none are as companionable as Morandi’s.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in