Rules in art exist to be broken but it takes chutzpah, which could explain why so many rule-breakers in modern figurative art were Jewish. Given that they were breaking the law by making figurative art in the first place, they went for broke.

Born a generation apart, Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943) and Leon Kossoff (1926-2019) had much in common. Both were brought up in Jewish working-class families with no pictures on the walls: Soutine the son of a Belarusian tailor; Kossoff, of a Ukrainian immigrant baker in London’s East End. Both were rule-breakers – Soutine because he didn’t have the patience for the rules, Kossoff because he had difficulty following them. Both were reserved in person, extravagant in paint.

Ironically, without the Jewish prohibition on figurative art Soutine might not have become an artist at all. The compensation he received after a beating for making a portrait of an old rabbi paid for his enrolment at Vilnius Drawing School in around 1910. By 1913 he was in Paris, at the École des Beaux Arts, but preferring the Louvre, where he alarmed a guard by falling into a trance before a Rembrandt painting, then prancing about shouting: ‘It’s so beautiful it maddens me!’

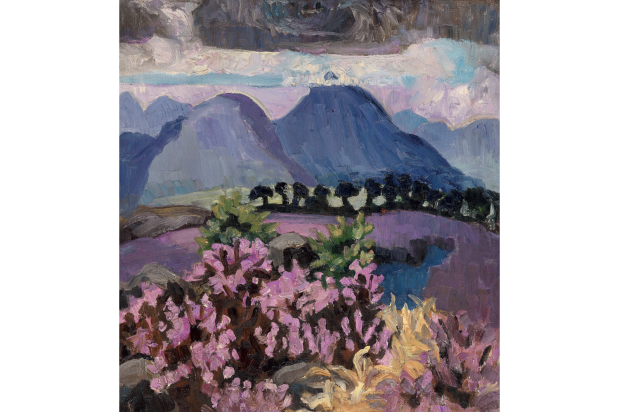

Limited to landscapes and portraits, Hastings Contemporary’s joint exhibition omits Soutine’s extraordinary still lifes of bloodied meat inspired by Rembrandt’s ‘Slaughtered Ox’, but there are lashings of blood-red in the waistcoats of his valets de chambre and in his landscapes, some of which evoke the jaws of hell. In 1918, as German long-range artillery reached Paris, he travelled south with his mate Modigliani and spent the next three years moving between Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera and Céret in the French Pyrenees, bashing out landscapes – around 200 – like there was no tomorrow.

Soutine’s French landscapes weren’t fauve, they were wild. Balmy breezes caress Derain’s Collioure, but hurricanes appear to join forces with earthquakes in Soutine’s Céret 20 miles inland. His ‘Place de Céret’ (c.1922) seems consumed by flames, while the gangly, swaying trees in his ‘Groupe d’Arbres’ (c.1922) throw their upper limbs around each other like drunken dancers.

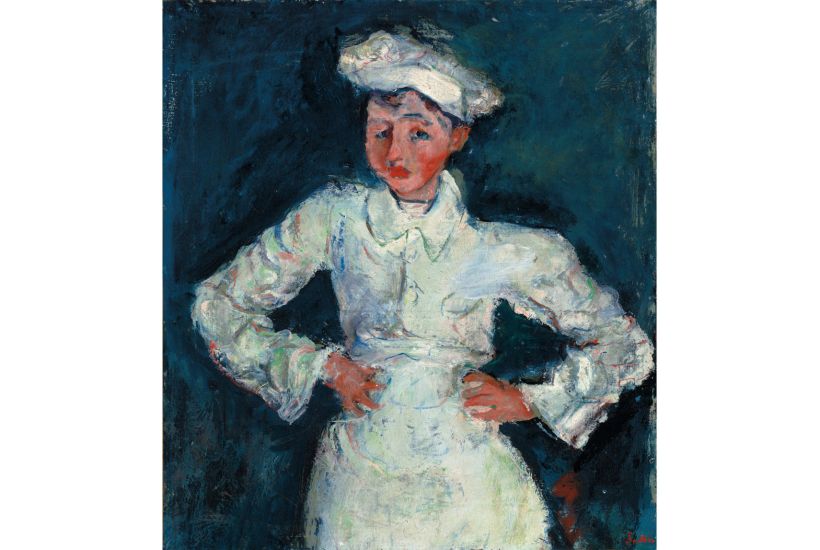

Modigliani had found his penniless friend a Paris dealer in Léopold Zborowski, but it seemed impossible to make money from these deranged landscapes. Yet on the 29-year-old artist’s return to Paris in 1922, a miracle happened: Albert C. Barnes walked into Zborowski’s gallery, fell in love with a Soutine portrait of a pastry chef and bulk-bought 52 of his paintings for 60,000 francs. Dragged along to meet the American pharmaceutical magnate the next morning, the artist conceived an intense dislike for him. Still, from then on he was known in artistic circles for his tailored suits and silk shirts.

There were no silk shirts for Kossoff, and no miracles – he was in his mid-forties when he was given his first retrospective at the Whitechapel in 1972 – yet he ploughed on through the furrows of paint he applied to his canvases. ‘Why do I paint so thickly? I don’t know,’ he admitted at the outset of his career. ‘It’s my natural way.’ But it was a way of conveying ‘the shuddering feel of the sprawling city’, a city constantly in the throes of destruction and renewal.

There’s a shiver of Soutine vertigo to the sheer drop in the foreground of ‘Demolition of the Old House, Dalston Junction, Summer 1974’, but even when lashed by storms of paint like ‘York Way Railway Bridge from Caledonian Road, Stormy Day’ (1967) Kossoff’s structures are never in danger of collapse. A disciple of David Bomberg – another Jewish rule-breaker – he followed his teacher’s injunction to ‘find the spirit in the mass’, and that meant establishing the mass in the first place. Soutine’s landscapes are all spirit, but Kossoff’s paintings, even on a small scale, are massive.

That goes for his figures too. Where Soutine’s subjects look small and doll-like, Kossoff’s feel monumental regardless of scale; in some cases, as in ‘Head Leaning on Hand’ (1959), the volume of paint renders them unreadable. Both painters sorely tested their sitters’ patience. Soutine often made them sit for hours before putting brush to canvas, then, ‘turning red as a crayfish’, finished in a fever. Kossoff endlessly scraped off and started again; his studio floor was carpeted in paint-sodden newspaper. His wife Rosalind sat on and off for five years for ‘Nude on a Red Bed, November-December 1972’, only for the picture to be completed in 15 minutes.

By the time of the red bed, light and colour had entered his work. ‘Railway Landscape near King’s Cross, Dark Day’ (1967) is so dark you have to grope your way along the ridges of impasto, but light floods the thinner paint of ‘Children’s Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon’ (1971). Kossoff’s search for ‘the living image’ was never more successful than in his evocations of the hubbub at the Willesden pool where he took his son David swimming; seeing the boy jumping in, we anticipate the splash.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in