During the 1964 debut of Carolee Schneemann’s ‘Meat Joy’ in Paris, a man in the audience tried to throttle the artist before being hauled off by three female spectators. Schneemann’s performance, an ‘exuberant sensory celebration of flesh’, involved semi-naked dancers tangling and grappling while bits of chicken, raw fish and hot dogs rained from above and buckets of paint sloshed underfoot.

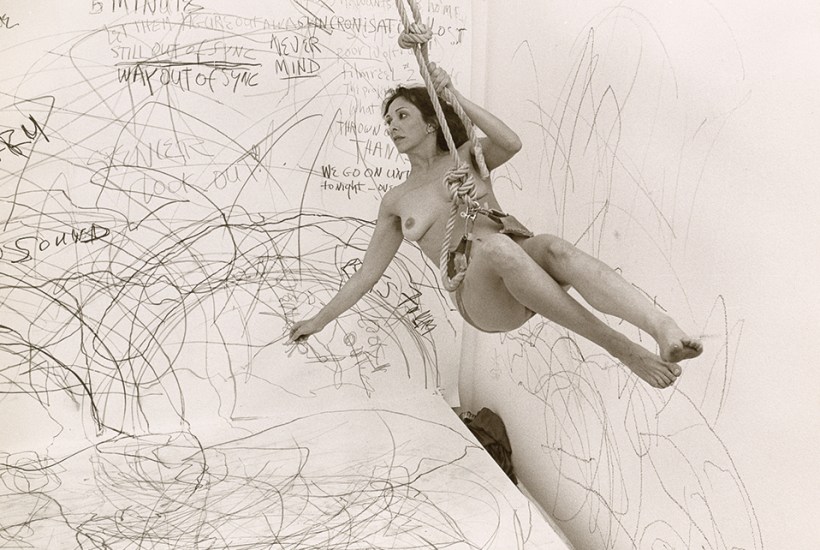

Since her expulsion from Bard College ten years earlier for the ‘moral turpitude’ of painting herself in the nude, Schneemann had made a name for getting naked while persisting in calling herself a painter – a claim that was just about tenable in the case of ‘Meat Joy’, less so in the case of ‘ICES STRIP/ISIS TRIP’ (1972), her one-woman performance on a London to Edinburgh festival train which started with a striptease in the dining car while reciting Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and ended with her roller-skating up and down the aisle.

Despite a police raid on the London performance of ‘Meat Joy’, Schneemann moved to the city for a three-year spell in 1969 and the Barbican has welcomed her back with a major show hailing her as a trailblazer of body politics. It’s an exhaustive survey, devoting several galleries to her unremarkable early abstract expressionist canvases and messy box-constructions before she hit her stride with photographs and films involving her body. At this point things get more interesting visually, if not logico-philosophically. Rejecting hierarchies she regarded as patriarchal, Schneemann gave everything equal artistic value. A wall is devoted to ‘Infinity Kisses (I)’ (1981-87), a grid of photographs of her daily tongue smooches with her cat Cluny. ‘THE CAT IS MY MEDIUM,’ she wrote of a previous pet. Oh, purr-leaze!

As Rossini said of Wagner, Schneemann has some good moments but some bad quarters of an hour. I liked early kinetic works such as ‘Music Box Music’ (1964) with its distorted nursery rhyme tapes tinkling to a halt like breaking glass, but I got awfully tired of her body. And I minded the mess and the lack of subtlety, which mattered when she got into activism. The thud of a mop hitting a TV screening her film ‘Souvenir of Lebanon’, in the installation ‘War Mop’ (1983)’, lands as heavily as its feminist point.

I didn’t want to throttle her, though by the end I was ready to throttle the curator for making the exhibition three times too long. The curator of the Stephen Cripps exhibition at Turner Contemporary has managed to squeeze a life’s work into two rooms. Admittedly the life in question ended with an accidental methadone overdose at the age of 29 in 1982, but it was frenetically productive.

Cripps blazed no trails – no one was mad enough to follow him – but he blazed brightly. Described as a pyrotechnic sculptor, he engineered legendary one-man shows – most famously at Acme Gallery from 1979 to 1981 – involving fireworks, gongs, bells, machine constructions and exploding bags of grocery dry goods. ‘The spectators would be showered with split peas or flour, dazzled by fountains of sparks and fire, sometimes even driven into the street by smoke,’ recalls musician and sometime collaborator David Toop. It was loud but never unsubtle. Cripps felt explosives had been given a bad press by war: ‘Some very gentle things can come from explosives.’

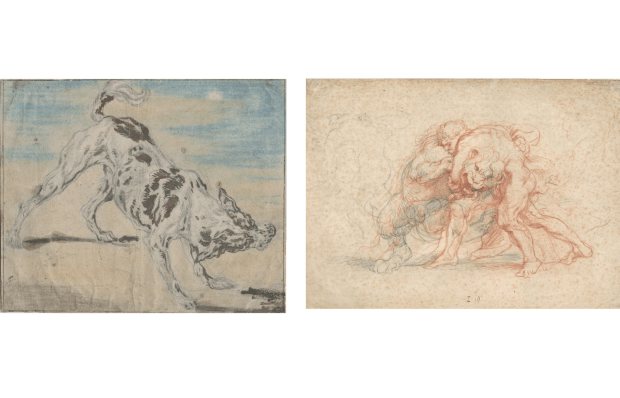

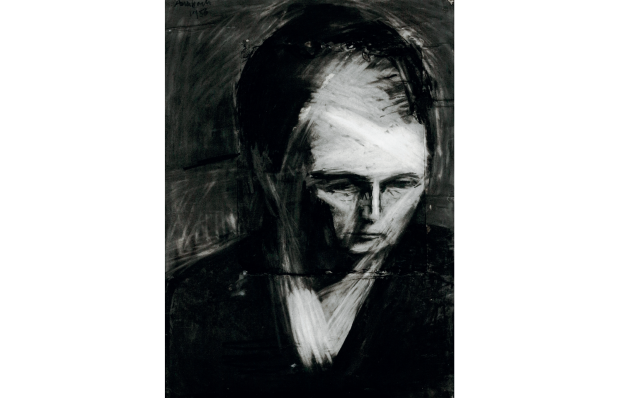

Understandably, his work was almost impossible to record. ‘If you blinked you missed it,’ says Toop. ‘If you witnessed it, you blinked anyway.’ Unlike Schneemann, Cripps had no interest in recording his performances; he was even reluctant to describe them as art. A photo of his Butler’s Wharf studio shows an enormous space littered with junk; the garden shed at the back was where he slept. The junk went into making ‘performing machines’ of which one rare survivor, a roving record player, is in the show. All that’s left of the others, if they ever took shape, are hundreds of marvellous annotated drawings that cover all surfaces in the exhibition. They include ‘Notes on a Dance for Jets and Helicopters’ and a drawing of a portable crematorium with arrows indicating where the ‘STIFFS’ go in and the ‘ASHES’ out.

Photographs show Cripps performing at Oxford’s Museum of Modern Art Oxford in 1979 during a Jackson Pollock exhibition at which the paintings ‘seemed to lose their visually active qualities’, recalled one witness, ‘and recede apologetically into the background’. The careers of both these artists are unthinkable today. Cripps eventually joined the London Fire Brigade to earn a crust – since they kept turning up to his gigs he figured he should join some of theirs – but he and Schneemann both survived outside a funding system. If their happenings happened, it was because they made them. Turner Contemporary’s health warning of ‘sudden loud noise and flashing lights’ on a film of a Cripps performance is a reminder of how far removed we now are from those heady days of happenings and how much poorer the art scene has become, even if artists are richer.

The post The careers of artists like Carolee Schneemann and Stephen Cripps are unthinkable today appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in