At what point did the ponderous autobiography get edged out by the slinky elliptical memoir? Perhaps around the stage we all realised that, as Stephen Hough puts it, ‘a complete autobiography is usually boring or indecent. It’s the person at the dinner table who just won’t stop talking’.

There’s certainly no holding forth (though perhaps just a little indecency) here. Hough, one senses, is more likely to be the man at the table looking on wryly, silent until, pressed, he’ll mention the time he just happened to end up playing the vibraphone ‘with Oscar Peterson’s trio on the telly’ or the two occasions he ‘seriously considered leaving the piano behind and becoming a priest’; or perhaps the moment he was snubbed by Leonard Bernstein (while himself failing to notice Greta Garbo), or the story of ‘Aunt’ Liz, who was in love with his father but sometimes shared a bed with his mother.

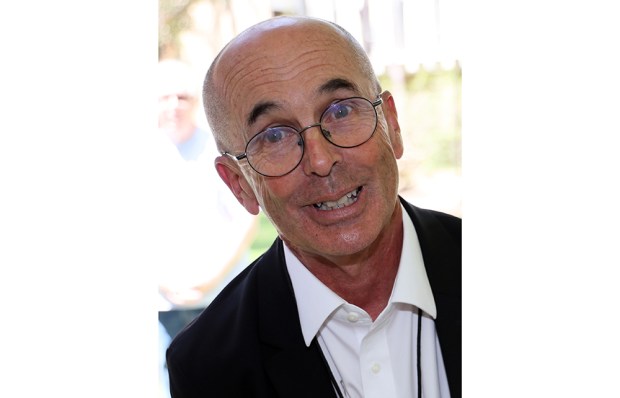

Hough is a much-awarded pianist and composer – the first ever classical artist to win a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (unofficially nicknamed a ‘Genius Grant’). But that’s all but irrelevant to Enough – a slim book about family and food, growing up gay in 1970s England, faith and, yes, music, that persistently wriggles away from spotlights and superlatives, from exceptionalism or grand narrative of any kind.

The subtitle – ‘Scenes from Childhood’ – gives a better sense of the snapshots and vignettes, the scattered collection of moments Hough spreads out for readers to arrange and order as they will. It’s the memoir you’d expect from an instinctive columnist whose publications (Hough was named one of 20 Living Polymaths by the Economist) already include the essay collection Rough Ideas (2019) and articles for everyone from the New York Times to the Guardian.

There’s a wilfulness to a book that ends just as we’d expect it to begin: in Carnegie Hall, ‘the most famous stage in the world’, where Hough is about to make his debut. But it’s more than that. To continue longer would be to reframe the story as teleological. Hough’s episodes (few are longer than a couple of pages) defy momentum or logic. Life is chaotic – additive rather than cumulative. All we can do, he suggests, is observe it carefully and with humour.

He tells a story about a dinner party given by his parents. In a lull in the conversation the not-yet-ten-year-old Stephen pipes up: ‘Mummy, why does my willy grow bigger?’ It’s no innocent faux pas. ‘I knew what I was saying. I meant it to be naughty and a little outrageous, and it wasn’t really a question. It was an assertion of identity – a joke, a tease, an erotic spark.’

It’s only a short stride from the precocious boy to the adult Hough, whose gleeful section headings (Doris Cox and her knickers; Coffee and being powsh; Shit in a bottle; Jimmy Savile – twice) play a game of provocation and pomp-puncturing, the classical great happy to declare:

Before I was five years old I had inserted my third finger up a neighbourhood boy’s rectum… (later I would use it to trill long at the top of the keyboard in the Liszt First Concerto).

If Hough delights in the bodily, the sensual shock teetering on titillation, he’s just as fascinated by ideas and people. His life-changing relationship with Catholicism is keenly drawn, even as he unpicks the vanity and sincere self-deception of his possible vocation. His portrait of a father who comes late to music and university – ‘unexpected, brilliant, unfulfilled’ – is tender and partial, an acknowledgement of a cipher never decoded, a life never fully lived.

He’s blissful on the social anthropology of coffee as a class-marker in 1970s Wirral – ‘The other Nescafé option, Blend 37, was considered a little risqué… too much of the unbuttoned shorts and the garlic bulbs swung around the shoulders’ – but is equally so on the complex game of conceal/reveal that is the life of a musician:

Sometimes I’ve played something faster than I intended to, not so as to catch the last train but to abscond from the embarrassment of sharing further private intimacies with the public.

This isn’t a music memoir. It’s a memoir of a man who happens to be a world-class musician. Hough’s is a life and career full of singularity, but this is a book about shared experiences: bad teachers and good ones; friends and comrades in arms; the first hamburger, visit to London, trip abroad; the pervasive shame and fear of homosexuality of the Aids generation.

When you lay them all out there’s a shared theme to many of the stories and characters: things that stay unspoken. Hough’s early desire to shock, his identity as playful provocateur, flourished in the gap between what was known and what was said – the product of a different time. Now we share everything, loudly and at top volume, and Hough’s quiet asides and gentle insinuations, his elisions and ellipses are more welcome than ever.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in