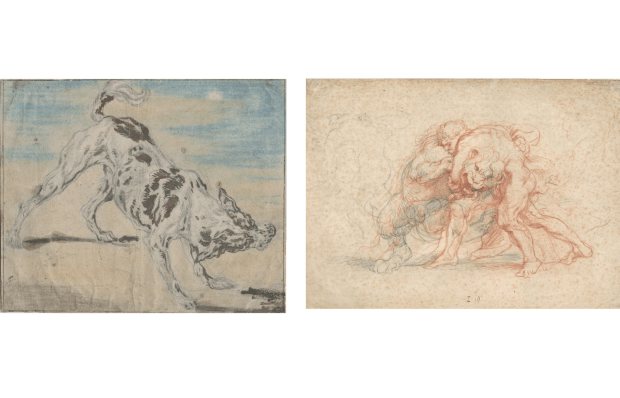

‘Psst! Someone’s coming!’ the skinny man with the ragged breeches and the bandaged jaw warns his fat companion out of the corner of his mouth. The two men, busy bundling sticks in a wood, look around apprehensively while a third man up a ladder attacks a tree with a billhook. The three of them are clearly up to no good, and we’ve caught them at it.

The focus of an intriguing little exhibition at the Barber Institute, ‘Two Peasants Binding Firewood’, c.1604-16, (see p31) was once thought to be by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, but as it’s one of several copies from the same workshop it has since been reattributed to his son. Pieter Bruegel the Elder didn’t churn them out; with a waiting list of collectors queuing to acquire his paintings, he didn’t need to. But when he died prematurely in his forties in 1569, he left a gap in the market that Pieter Brueghel the Younger filled.

A versatile artist, Pieter the Elder moved with ease between religious subjects and landscape paintings, but the pictures for which he is best remembered are the village scenes of rustic jollity that earned him the sobriquet ‘Peasant Bruegel’ – the scenes Pieter the Younger would go on to establish as the Brueghel brand, cashing in on their popularity with endless copies and pastiches.

‘Two Peasants Binding Firewood’ is a sort of spoof on the pious labours of the month illustrated in contemporary Books of Hours, like the beautiful example by Simon Bening (1483-61) showing legit woodcutters chopping down a tree. But it could also illustrate a proverb, a fashionable subject for paintings at the time. Pieter Bruegel the Elder crammed more than 100 into his much-copied composition ‘Netherlandish Proverbs’ (1559), and a version by a follower in the show includes a man with a bandaged jaw just like our firewood thief apparently suffering from proverbial ‘toothache behind the ear’ – a symptom of a malingerer or a cheat.

The 16th century was the golden age of the proverb, when old saws were not just the province of old maids but objects of serious academic study. In 1500 no less a scholar than Erasmus collected 818 into an Adagiorium Collectanea that proved so popular it ran to several editions; the final one, published in 1536, the year of his death, included 4,151 entries. The 1526 edition is open at a page quoting a proverb that could have inspired Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s painting: ‘When the tree is felled, everyone gathers the firewood’ – in other words, we profit from others’ misfortunes.

Whatever its proverbial meaning, ‘Two Peasants Binding Firewood’ is a visual satire on stock types. Like D.C. Thomson comics, Brueghel peasant paintings depend on the appeal of familiar characters. (There’s probably a thesis to be written about what the Beano owes to the Brueghels.) The thin firewood thief is the stock type of the itinerant vagabond, while his red-trousered companion epitomises the well-fed peasant regularly seen strutting his stuff in the standard Brueghelian village knees-up-cum-booze-up. The two types are comically compared and contrasted in a pair of satirical prints after Pieter Bruegel the Elder: in ‘The Fat Kitchen’, overweight gluttons gorge themselves at a table groaning with food while a starving vagabond is bundled out the door; in ‘The Thin Kitchen’, a grotesque lard arse strenuously resists an invitation from a couple of scarecrows to share a wretched meal of mussel shells and turnips.

Hugely popular, this pair of body-shaming prints was issued and reissued throughout the 16h century. The concept of fattism didn’t exist then: to the target audience for these images, fat equalled greedy and thin meant hungry and liable to thieve. Compared with the golden age of the proverb, our own age is dross. A good proverb depends on typecasting, disregarding differences. The only new coinages our age of offence seems capable of producing are pointless pleonasms like: ‘It is what it is.’

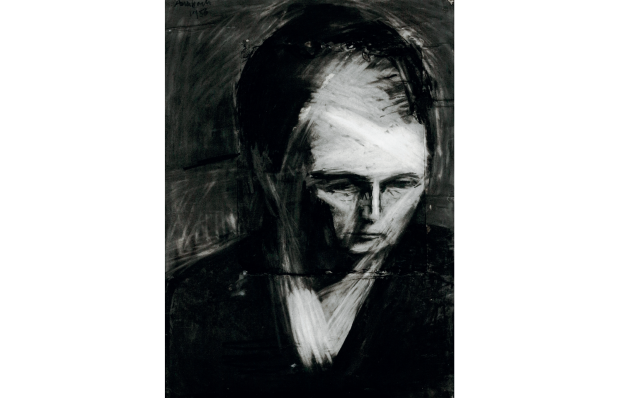

In art, however, typecasting has its limits and Pieter Brueghel the Younger was circumscribed by them. His workshop knocked off 100 copies of his bestselling ‘Wedding Dance in the Open Air’ (c.1607-14) – a riff on his father’s famous painting of peasant nuptials – of which he is thought to have personally painted 30. Thirty! His younger brother Jan Brueghel the Elder, meanwhile, got to do his own thing. He did occasionally stoop to a rustic subject like the ‘Peasant Wedding Feast’ (c.1597) drawing in this show, but when a similar scene appears in his painting ‘Flemish Fair’ (1600) in the Royal Collection, the view opens out to a fantasy mountain landscape. Jan was free to indulge his imagination – and is consequently regarded as the better artist – while Pieter maintained the Peasant Bruegel brand. How did he feel about this? Pissed off, to judge from his dissatisfied expression in a 1630 portrait etching by Anthony van Dyck that labels the artist, then in his late sixties, as ‘Pictor Ruralium Actionum’ – ‘a painter of rural doings’.

The post Brueghel’s peasant paintings were the D.C. Thomson comics of the 17th century appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in