At the Paris International Exhibition of 1867, Mark Twain was mesmerised by a life-sized silver swan with ‘a living grace about his movement and a living intelligence in his eyes… swimming about as comfortably and unconcernedly as if he had been born in a morass instead of a jeweller’s shop’.

The jeweller’s shop this mechanical marvel had been born in 100 years earlier was Cox’s Jewelry Museum in London, but its mechanism of 700 components powered by three clockwork motors was the invention of Belgian-born horologist John Joseph Merlin (1735-1803), aka ‘the Ingenious Mechanic’.

Turning its head on its flexible neck and dipping its beak to catch a fish in a glittering pool of rotating glass rods – all to musical accompaniment – the swan was the talking point of the Paris exhibition, where it also caught the eye of John Bowes and his French wife Joséphine, on the lookout for objets d’art for the museum they planned to open in their château then under construction in Barnard Castle. As the £2,000 price tag far exceeded the £10 acquisitions limit the couple had set themselves, they resisted temptation, but five years later they picked the swan up for a song – at £200, still the biggest ticket item in their collection.

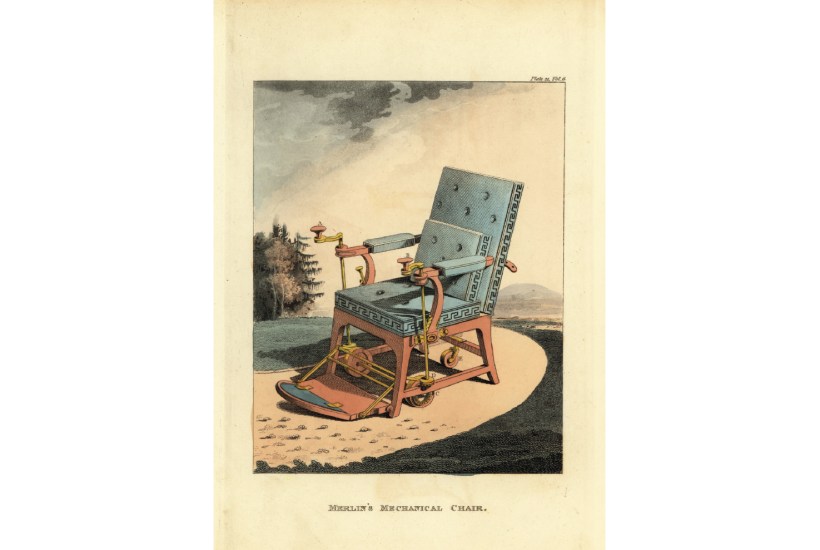

Forget the El Greco, the Goya and the Canalettos: since the Bowes Museum’s opening in 1892 the Silver Swan has been its leading attraction, drawing spellbound visitors to its afternoon performances. But during Covid, like so much else, it ground to a halt and it now sits languishing in its dedicated gallery while the Bowes raises the £200,000 needed for repairs. In the meantime, the museum is marking 250 years since the swan’s debut at Cox’s Museum with an exhibition celebrating the delights of automata. The presiding genius of the show is the wizard Merlin, represented by a Gainsborough portrait and a selection of his multifarious inventions, including the first self-propelled wheelchair, a clockwork-driven vertical spit anticipating the doner kebab and the first pair of inline roller skates. His oscillating ‘Hygeian Swing’, illustrated in action in Sydney Gardens, Bath, in an amusing watercolour by John Nixon, was said to do wonders for pulmonary consumptions.

As well as clocks – the first skeleton clock is one of two Merlin timepieces on show – he designed stringed instruments. The displays include a Merlin violin, viola and cello and a patent for a harpsichord with a pianoforte action. An astute publicist, Merlin got Johann Christian Bach to perform on this compound instrument but demonstrated other inventions himself, scooting around the Pantheon in his ‘Gouty Chair’ and showing off his ‘skaites’ at a Soho Square soirée while playing the violin. As they had no brakes the stunt famously ended when he ‘impelled himself against a mirror of more than five hundred pounds value, dashed it to atoms, broke his instrument to pieces and wounded himself most severely’.

The Age of Enlightenment had an insatiable appetite for technological novelties, and Merlin was not the only ingenious mechanic to cater to it. In a video from the Paris Arts and Crafts Museum you see a miniature model of Marie Antoinette, crafted by Pierre Kintzing and David Roentgen, nimbly hammering at a dulcimer (1784); her action is charmingly lifelike, though her playing sounds a bit, well, mechanical. The songbird in a contemporary gilded bird-cage clock by Swiss horologist Pierre Jaquet-Droz is now immobile and silent, but the family firm is still in the luxury clockwork business. The limited edition Rolling Stones Automaton watch Jaquet-Droz launched in March – customisable with a miniature Ronnie Wood Fender Strat or Charlie Watts drum kit – will set you back a quarter of a million dollars. Perhaps the firm would like to sponsor the Silver Swan’s repairs?

Adult visitors have been hogging the ten contemporary push-and-play automata

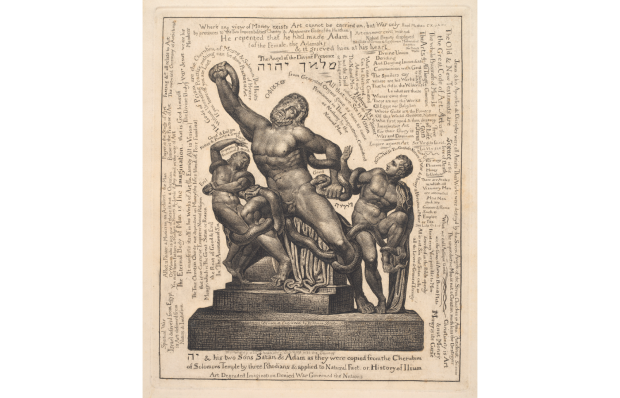

Our human fascination with clockwork is perennial. The show’s curator Vicky Sturrs complained to me that adult visitors have been hogging the ten contemporary push-and-play automata on loan from the Cabaret Mechanical Theatre collective, preventing children from getting at the buttons. But there is a serious side to all of this, as the loan of Charles Babbage’s ‘Difference Engine No. 1’ (1832) by the Science Museum proves. As a Devon schoolboy on a trip to London Babbage visited Merlin’s Mechanical Museum off Hanover Square, where he was entranced by a pair of female automata, one ‘an admirable danseuse’ who ‘attitudinised in a most fascinating manner’. At the 1834 sale of Merlin’s collection 30 years after the inventor’s death, Babbage bought the fascinating danseuse for £34. Who knows how her mechanical charms might have inspired the inventor of the first automatic calculator?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in