There’s a nice irony to the title Salon Paintings when the salon in question is a barbershop, an irony that won’t be lost on Hurvin Anderson. Born to Jamaican parents in Birmingham in 1965 and trained at Wimbledon and the Royal College at a time when the Euston Road School discipline of measured observation was still being taught in English art schools, Anderson is steeped in the European painting tradition. Explaining the fascination of the mirrored interior of the Birmingham barbershop that first inspired the series of paintings in his exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield – begun in 2006 and completed this year – he compares it to Manet’s ‘Bar at the Folies-Bergère’: the barbershop as the Caribbean equivalent of the impressionist café.

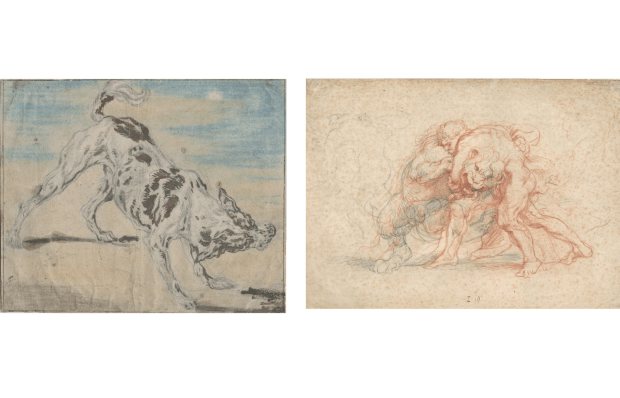

That’s where any obvious parallel with impressionism ends. Although Anderson’s Caribbean landscapes can be impressionistically painted, the Barbershop series takes its cue from collage. It’s no accident that Richard Hamilton and Patrick Caulfield are among the modern British artists he has selected for an accompanying display; he shares their fondness for the sharp edge.

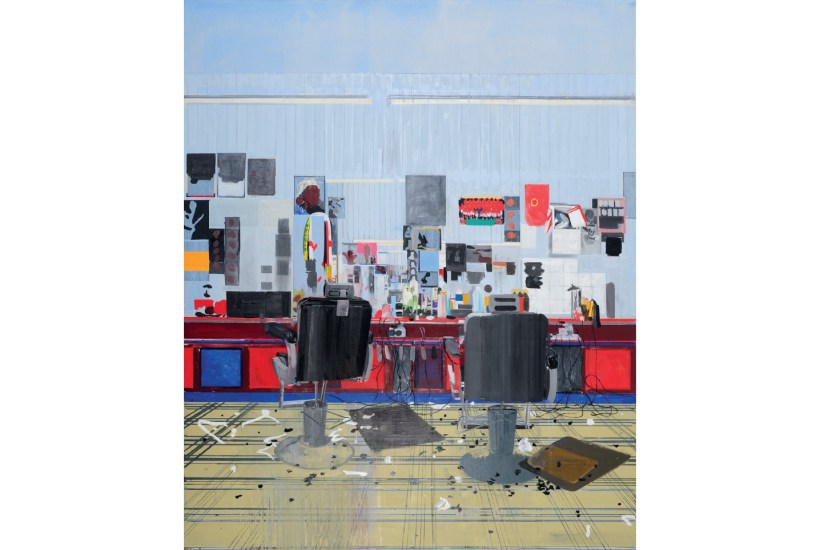

Anderson’s mirrored barbershops are battlegrounds between figuration and abstraction in which the empty chairs and counter exist in real space while the photos of sporting and political heroes on the walls, reflected in the glass, recede kaleidoscopically into infinity. There’s always a push-me-pull-you between flatness and depth in his work and in this series the flatness is winning. But the miniature skylines of bottles and jars of pomade on the counter are reminiscent of still lifes by Morandi. A part of him wants to draw you in with authentic detail, inviting you to put on the cape, sit in the chair and choose your style from the menu on the wall: Fade, Flat Top, High Top, Side Part, Trim Shave, Skiffle. In the final painting, ‘Shear Cut’ (2023), the chairs are occupied; the series that started with an empty salon has ended with sitters. ‘There’s a sort of energy that gets generated when you work from life,’ he admits.

How to generate that energy is the question facing the 41 American, German and British artists in a new exhibition of contemporary abstract painting spread across Gagosian’s two Mayfair galleries. With each artist represented by a single work, the show is a hubbub of different voices. For what purports to be a universal language, contemporary abstraction has a lot of dialects. There are shades of minimalism and colour field painting – and expressionist brushwork is alive and dripping – but in the absence of a movement of the moment it’s a free-for-all. Substance becomes as important as form; when nothing is represented, materials matter. As Suzan Frecon puts it: ‘The content is the paint.’

There are limits to what you can do with paint and they’re tested here. Spray-painted squiggles, silkscreened Ben Day dots, dripped and drizzled paint, spattered powder pigment, mists of turps and worms of colour squeezed straight from the tube in Mark Grotjahn’s ‘Untitled (Backcountry 54.99)’, (2023), overpainted in stripes like Signal toothpaste. There’s actual collage, with all manner of things stuck to the canvas – tobacco, string, a paper bag, a balloon and what look like crystallised ginger chunks dipped in silver paint in Frank Bowling’s ‘Passtheball’ (2022) – and there’s fake collage with trompe-l’oeil overlaps. Everywhere there are telltale tracks of mechanical wiping in homage to the godfather of the squeegee, Gerhard Richter, who wipes his own ‘Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting) (952-1)’ (2017) into a grey sludge. Cecily Brown is in a small minority who stick to brushwork worked with a brush.

It’s not surprising to find so much variety in a visual language defined by what it is not. Among the artists’ commentaries in the catalogue there’s a lot of talk about ‘openness’, ‘ambiguity’ and the absence of planning – ‘like a baby trying to walk’, says Frank Bowling; ‘doomed to work in between hoping and groping’, says Amy Sillman – and much discussion about how you know when a painting is finished. For Tomma Abts, it’s when ‘the painting comes alive’.

‘Salon painting’ is a dirty word in figuration and ‘lobby painting’ in abstraction, both implying that the work lacks life. There are no lobby paintings in this show, but too many bear scars of the artist’s struggle to wring life from the non-representational. The most alive are the most effortless-seeming: the raw graffiti-like gestures of ‘Manifestation’ (2020-22) by Oscar Murillo, for whom painting is ‘a release of energy, a physical kind of exercise’, and the free-floating forms and immersive colours of ‘And willingly imprinting the memory of my mistakes’ (2023) by Jadé Fadojutimi, a lucky artist for whom ‘fear instantly evaporates’ on entering her studio. But it’s Vija Celmins, whose ‘Night Sky #22’ (2015-18) was three years in the making, who best sums up my feelings about this show. ‘Making art is really a shot in the dark… I’m amazed so many people are willing to do it.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in