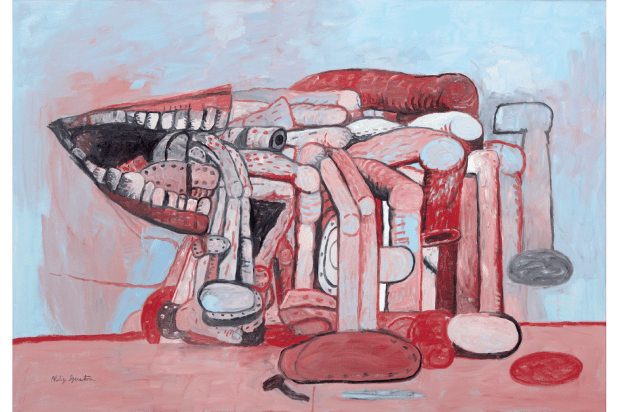

Philip Guston is hard to dislike. The most damning critique levied against the canonical mid-century American painter is that he is too uncontroversial, his appeal too broad, his approach altogether too winsome. None of that stopped the team behind Philip Guston Now – a travelling mega-survey of his work, which will reach Tate Modern in 2023 – from announcing otherwise. In 2020, the year the show was due to open, the curators announced that in light of the ‘racial justice movement’, the artist’s works might now legitimately be read as racist, and the show could not go forward as planned. This was and is quite obviously nonsense. The works in question are marshmallow-like renderings of Klansmen in absurd, mundane scenes. The KKK were a preoccupation for Guston, himself a Jew and target of the Klan. The team decided to bring in ‘more diverse voices… that allow us to appreciate the context in which Guston worked’, as though it were a year-long screening of Triumph of the Will. ‘That process will take time.’ Initially quoting four years to heroically save the artist’s works from themselves, by some miracle, they managed to do it in just two. The show contains 100 works.

I was cautiously optimistic that sense had prevailed when I learned the show was finally opening. I shouldn’t have been.

Perhaps the most embarrassing misjudgment of the exhibition occurs before you enter the gallery. You are given a copy of ‘Emotional Preparedness for Philip Guston Now’, a mawkish, overwrought trigger warning seemingly designed to offend and confuse anyone familiar with Guston’s work, and dissuade anyone unfamiliar from looking at it. The team hired Ginger Klee, a therapist who specialises in ‘acculturative stress’ of the ‘BIPOC and/or LGBTQIAPD+’ and ‘fat’ communities, who has no apparent knowledge of art, to write this sermon. As with all great texts of the genre, it starts by bestowing rights: ‘To feel your feelings… as a person of color or not.’ Thanks? Our guide continues: ‘My advice to you on this complex journey is to embrace that guilt and the journey… I encourage you to lean into the discomfort of this work and remind you that… we also must prioritise rest.’

The sole principle guiding the show seems to be a contempt for Guston. The hang is scattered and sloppy. It unedifyingly blends together Guston’s juvenilia (mostly politically overt, second-rate surrealism) with much more developed work from later in his career. As his formative work is neither notable nor flattering, it is odd to find so much of it in the show. The curators shamefully use some of his later small pieces – regarded as among his most important – as decorative space-fillers, hanging them in such a way that they’re barely in view, never mind clearly labelled or interpreted.

They have vitrines with sliding tops to hide some objects, including a newspaper clipping about a very early piece he made condemning the Klan, which was vandalised by them. The work is not significant, except that its destruction is likely what spurred Guston’s later paintings that subvert the menace of the Klan with humour. The only other instance I can think of where artists were simultaneously exhibited, physically censored, and verbally chastised is the Nazi’s Degenerate Art show in 1937.

Without fanfare, or indeed preparedness, a three-projector montage shows the Kent State shootings, US aircraft napalm–bombing Vietnam and close-ups of Richard Nixon in a vestibule. It was an odd way to let us know we have moved from the 1930s to the cusp of 1970. Odder still, a portentous text alerts us to the fact that they have taken the precaution of installing an emergency exit in case visitors need immediate safety from the paintings in the next room. Extra copies of Ms Klee’s tract are available.

The real and primary offence of this next room is that it is amateurishly over-hung. It brims with some of Guston’s best work, including three large paintings of the farcical hooded men. In the middle of the room is a cheap re-staging of his most famous work, ‘The Studio’, showing a Klansman risibly painting a self-portrait and smoking. A video speculating about hidden Klansmen in his non-Klansman work plays in the education suite, where a wall text goes some way to explain the dereliction of the show: ‘Despite the art world telling us that Guston mattered – to us, it felt the opposite.’

The tragedy of Philip Guston Now is that they’ve managed to include all the dreadful trappings of Now and almost no Philip Guston.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The exhibition is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston from 23 October to 15 January 2023, the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC from 26 February 2023 to 27 August 2023 and at Tate Modern from 3 October 2023 to 4 February 2024.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in