In March 2020, as the health service prepared for the first Covid wave, NHS England encouraged GPs to adopt a new system called ‘total triage’. The aim was to reduce the number of patients in clinics in order to protect GPs, their staff and patients themselves from the virus. If patients hoped this system was a temporary, emergency measure, they were wrong.

Under ‘total triage’, patients had to provide far more details of their (sometimes sensitive and embarrassing) symptoms to a receptionist or on an e-consultation form. They would then be allocated a telephone consultation with their GP or another health professional such as a nurse, pharmacist or physiotherapist. In the first year of the pandemic, records show there were 90 million fewer face-to-face appointments – a drop of 40 per cent. Of these, 70 million happened on the phone instead, but the figures still show tens of millions fewer appointments overall.

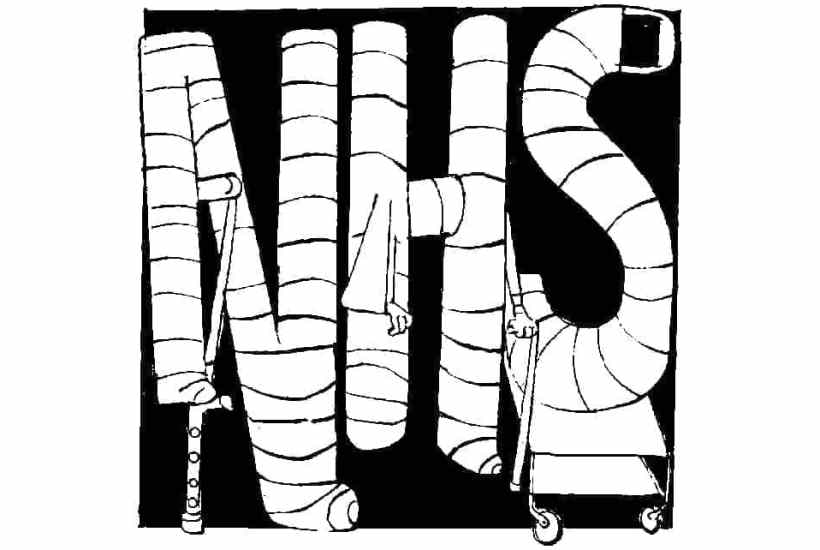

While Britain is moving on from Covid, many GP surgeries are emphatically not. It’s still quite common to see signs telling patients to go away unless they have booked an appointment via internet or phone. ‘Total triage’ has meant that GPs have had far less opportunity to examine patients, which has led to delayed or failed diagnoses. The burden of urgent care has rapidly transferred to A&E, where pressure has become intense. At the last count 24,000 patients per month had to wait for more than 12 hours to be seen. The reason is simple: general practice is broken.

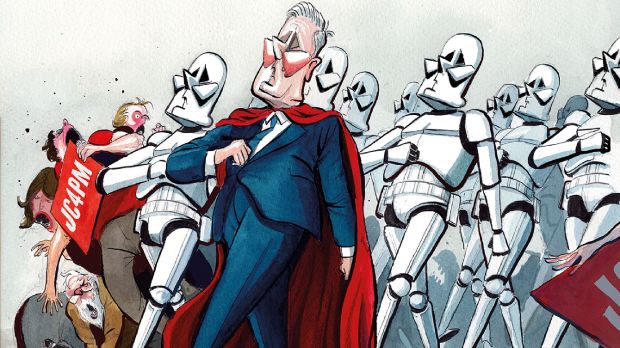

Rather than acknowledge these problems, the unions – the British Medical Association and Royal College of GPs – insist that all can be solved by their long-term mantra of ‘more investment’. The government has swallowed the bait and has promised 6,000 more doctors within two years. This unachievable goal is doomed to failure, as was Jeremy Hunt’s 2015 promise of 5,000 more GPs by 2020. Experienced GPs are leaving the profession in droves and medical students, after they complete their placements in general practice and see the insurmountable problems, are reluctant to fill the gaps. The number of fully qualified GPs in the NHS has changed little in the past three years.

And the patients? A recent poll by the British Social Attitudes Survey has shown that public satisfaction with GP services is at its lowest since the surveys began in 1983. NHS spending has trebled since then.

The new GP gravy train started its journey back in 2004 with the revised GP contract, which was a disaster for patient care. GPs were only allowed to take on clinical responsibility for patients during weekday office hours. They had no contractual responsibility for out-of-hours care (i.e. at night, at weekends or bank holidays). Many doctors were astonished by this concession from the Blair government. Others negotiated lucrative contracts to fill the resulting gaps in their schedules.

This change was the start of the decline of general practice. The diagnosis and treatment of emergencies is, of course, at the heart of clinical medicine and cannot be restricted to office hours. A lack of exposure to such emergencies, especially for trainees, was always going to result in less skilled doctors.

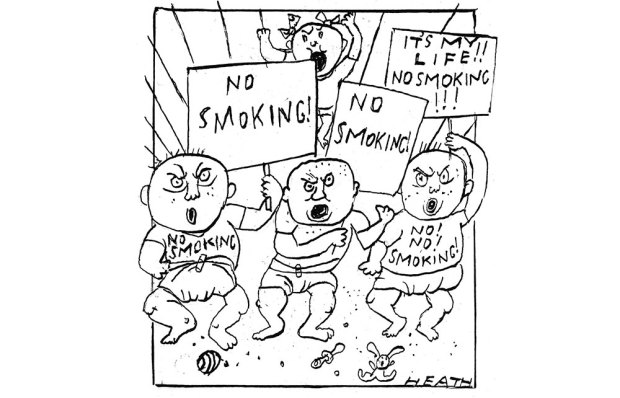

Even with a reduced workload, there has been a growing trend for GPs to work part-time, compromising patient care even further. Currently, an astonishing 58 per cent of GPs work three days or fewer per week. We’re told that seeing patients is such a stressful business that part-time working is the only way to prevent burnout. In my 33 years working as an NHS consultant surgeon, I don’t remember this ever happening to heart, brain, cancer or other specialists who take life and death decisions every day. GPs’ work is far less complicated. Why should they be so badly affected by burnout?

Last year, a survey of GPs found one in three saying that they would like to quit direct patient care within five years. Why? When the Warwick academics asked GPs what would make them change their minds, one of the most popular responses was having more time to spend with patients, and less being taken up with NHS paperwork.

A step down from part-time doctoring is locum work: the refuge for freelance doctors who wish to avoid the constraints of a permanent job. The National Association of Sessional GPs says there are now 17,000 GP locums, one in every four GPs. The use of so many temporary staff prevents any continuity of care, which is the service patients most value. It is difficult to understand why anyone with a vocational calling would be satisfied with long-term or permanent locum work. Perhaps this is a fault of the selection process to medical school or the unproven aptitude tests. (A survey of trainees recently found that a third of them reported bullying in GP practices, ‘most commonly from patients’.)

When it comes to the failing efficacy of general practice, cancer care is the most obvious concern. A study published in the Lancet Oncology recently reported that, even before the pandemic, more than a third of cancers were being diagnosed in A&E: that is to say, at a dangerously late stage. A comparison was made with six other high-income countries and Britain was the worst but one. It has long been known that cancer survival in the UK lags behind other comparable countries. Late presentation is usually to blame. Earlier diagnosis offers the only hope of improving survival.

Some cancers – breast, cervix and colon/rectum – can be screened for. For the remainder, we must depend on the intuition and diagnostic skills of GPs. Stomach, liver, pancreas, lung and ovarian cancer present with vague symptoms of low predictive value, which is why telephone or virtual consultations are unlikely to be of much use. The vital clue may only be spotted by clinical examination, which is why in-person, face-to-face consultations must be restored as soon as possible.

It’s an urgent problem. But in the NHS system, GPs have no financial incentive to give patients the service they have the right to expect. What is the difference in salary between the best GP in the country and the worst? On a sessional basis, there is none. The only incentive to provide a better service is professional pride and personal commitment. If there was competition in general practice and if GPs were paid on a fee for service basis, then primary care would look quite different.

General practice used to be a cornerstone of the NHS. It is no longer. I have been criticised and trolled for voicing my concerns. Why do I persist? Because I gave my working life to the NHS. I care deeply about its future. I want to see it preserved and improved, not eroded. General practice needs radical reform. Patients deserve better.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in