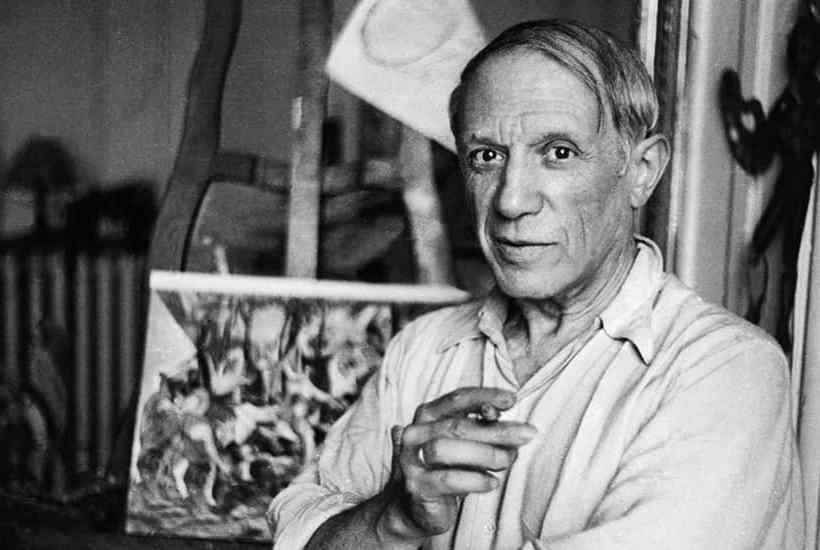

The decade 1933-43 was one of busy erotic multi-tasking by the deft and diminutive Pablo Picasso. It took him the best part of ten years to effect a separation from the reluctant Olga Khokhlova, his ex-ballerina wife, retired injured from the Diaghilev Ballets Russes. Legal proceedings were triggered by her discovery of Picasso’s affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter (aged 17 when Picasso picked her up in 1927 outside the Galeries Lafayette).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in