Of the 101 Australian military personnel who have been awarded the Victoria Cross, our highest honour for bravery, most lie in recognised graves. But five of our fallen have no known final resting place.

To explain further, when the recipients of the Crosses were given their honour, many were awarded posthumously – they had died in the action in which they performed their feats of bravery. But their bodies were recovered, and later buried or cremated.

Many of the other Cross recipients survived warfare. Later they died, and the usual process followed – they were given a funeral. But often they were overseas when that happened, often reflecting the fact that many of these military personnel were born overseas, and had sometimes gone to the country of their birth after their Australian military service. So 37 of our 101 VCs are interred in other countries. Perhaps the most remote of these is the grave of Sergeant Samuel Pearse, who earned his VC in 1919. He is buried in a military cemetery near the Obozerskaya railway station, between Emtsa and Archangel, in North Russia.

Of the VC recipients interred in Australia, most lie in the states or territories where they spent the rest of their lives. They are distributed as follows: ACT 2, NSW 13, Queensland 5, SA 5, Tas 3, Victoria 18, WA 9.

The Northern Territory’s only VC was Albert Borella from WWI. He was buried in Albury-Wadonga, where he spent his final years. Four VCs are still living with us. And five of our 101 have no known grave.

Sixty-four Victoria Crosses went to the Australian Army in World War I. The Gallipoli campaign saw nine of these in only around six months, testimony to the fierce and close quarter fighting. When Gallipoli was closed down the AIF moved to the Western Front, where they were joined by thousands more Australians for almost three more years or fighting. Four of the five ‘no known grave’ VCs come from WWI, although curiously, one received his VC for a WWI action, but died in WWII.

Two had fairly conventional ends. Lance-Corporal Alexander Burton died in 1915. Born in Kyneton, Victoria, in 1893, Burton, an ironmonger, joined the Australian Imperial Force and was posted to the 7th Battalion. Although he missed the landing on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, he saw it from the deck of a hospital ship, where he was being treated for an infection. A week later he was in the trenches, fighting in different areas with his Battalion.

On 9 August at Lone Pine, the Turks launched a counter-attack on a newly captured trench commanded by Lieutenant Frederick Tubb. The Turks advanced and knocked over a sandbag barricade but Tubb, a Corporal William Dunstan, and Burton rebuilt it. The enemy twice more destroyed the barricade but each time was driven off and the barricade rebuilt. Burton was killed by a bomb while he was building up the parapet.

Burton’s body was not recovered. Although this is difficult to understand, it reflects the fact that often soft-skinned humans in combat can be literally blown apart. To make matters worse their bodies can lie in a contested area – often know as ‘No Man’s Land’ where they might lie for some time. Others may lie in the same area. When one side or the other takes that part of the battlefield hasty burials often result, usually into mass graves. It is an unpleasant aspect of battlefields, but reflects the fact that it is urgent necessity, not nicety, that is needed at the time. Burton has no known grave. He is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial. Private Thomas Cooke died in 1916. He was 35 years old, comparatively old for a private, and married with a family. Born in New Zealand, he had migrated to Australia shortly before the war.

In the initial attack on Pozières, in France, Cooke’s battalion captured ground, and held on under heavy enemy artillery fire and counter-attacks. Cooke was in a Lewis machinegun team working in a dangerous position. After the others with him were killed or wounded, he remained fighting at his post. Cooke was later found dead at his gun. His body was lost in later fighting. He has no known grave site. Cooke’s name is recorded on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial and on the war memorial in Kaikōura NZ, his town of birth.

Captain Alfred Shout, despite being an Army soldier in WWI, was curiously buried at sea.Shout had served in the Boer War, and following that conflict worked as a carpenter in Sydney, while serving part-time as an officer in the local militia. He joined the AIF when war was declared and took part in the landing on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. He was awarded the Military Cross and Mentioned in Despatches for actions over the next month.

In August at Lone Pine fighting Shout was involved in an action that saw him attacking an enemy trench, killing eight Turks with grenades. Later that day one of the locally-made grenades exploded prematurely, causing horrendous injuries. Shout died on a hospital ship of his injuries two days later. He was buried at sea, with Victoria Cross awarded two months later. He is commemorated at the Lone Pine Memorial, Gallipoli, Turkey.

Corporal Walter Brown served in both WWI and II. A Tasmanian, he enlisted in 1915 in the Light Horse before transferring to the infantry. He gained the Distinguished Conduct Medal in 1917 for bravery before he was involved in an attack on a German trench at Villers-Bretonneux in France. He then attacked an enemy sniper with two Mills bombs, and caused the surrender of several other enemy soldiers. He was awarded the Victoria Cross.

When WWII broke out, Brown volunteered for the Army, despite being married and of older years. He went missing after the fall of Singapore in February 1942, when he was last sighted declaring, ‘no surrender for me’. He likely died fighting in the confusion surrounding the island’s last stand.

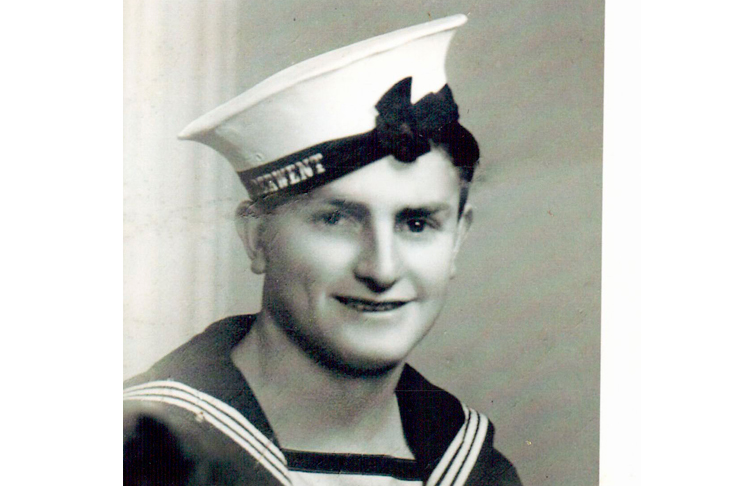

Teddy Sheean is the last of the five with no known grave. HMAS Armidale was attacked relentlessly from the skies by Japanese aircraft on 1 December 1941, and hit by at least one torpedo. Despite ‘Abandon Ship’ being ordered, he returned to his 20mm Oerlikon gun to defend his shipmates from the strafing and circling enemy. Armidale has not been found. She lies in waters closer to Timor than Australia, and a search for her has begun at least in analysing the records of the action. It is a sad aspect for the bravest of our brave that they lie in unmarked graves. But at least we can remember them by recalling their stories.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Military historian Dr Tom Lewis OAM’s latest books include Teddy Sheean VC, and – for upper primary/junior secondary – Australia Remembers 4: the Bombing of Darwin, both released by Big Sky Publishing.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in