I was born, grew up and have lived in Russia all of my 45 years. This means that I belong to a state that was established by force, expanded by force and is maintained by force. In this, of course, Russia is not alone: this fact is true of several countries. But the world has changed and other empires have learned new ways. For a brief 15 years from the mid-eighties onwards, there was an illusion we would too. Alas, now we’re on the same old road again.

My countrymen, it seems, will make huge sacrifices for the sake of a phantom national pride. It’s this pride that’s now sending Russian forces out into Ukraine. It’s the same pride that the Ukrainians – with their rejection of us – have bruised. ‘They never liked us, they don’t respect us, now at least they will fear us,’ people around me say to justify Putin’s invasion of the country.

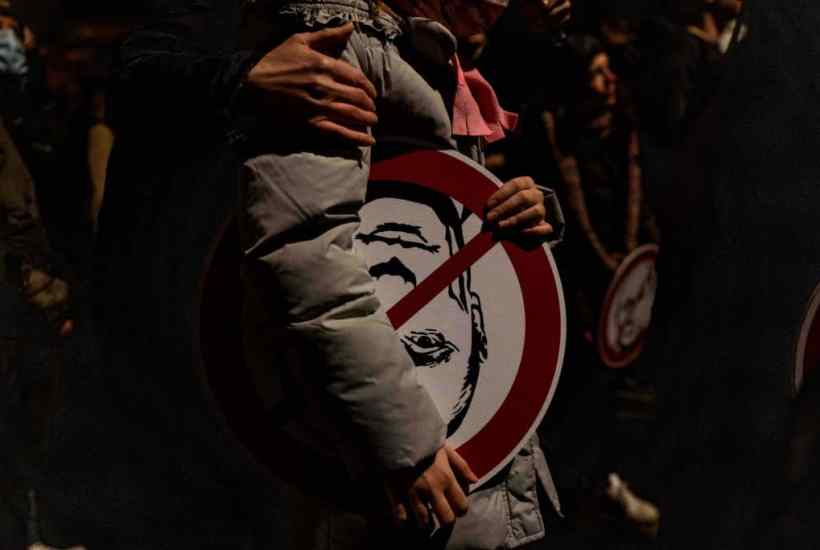

Putin too, for some time, has been living in an imaginary world of big abstract notions like ‘national interests’ and ‘strategic security’. Behind all this he wants, I’m sure, just to rebuild the Soviet Union in another form. He craves his place in history as Tsar Vladimir who united the ‘brotherhood of nations’ and took revenge on the West for winning the Cold War. In his zero-sum view of the world, the collapse of the USSR was ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20thCentury.’ The thought that its mere existence might have been even more catastrophic doesn’t occur to him. Nor that no one gained more from its collapse than the people who lived under it. The notion of normal people’s problems and normal people’s lives doesn’t enter into his calculations, nor the lives of the young soldiers he’s squandering. So why, we’re asked, don’t we rise up against him?

Part of it is Stockholm syndrome: a hostage begins to sympathise with their captor, the ultimate authority. It’s hard to acknowledge that for 23 years – the length of Putin’s rule – you’ve been supporting someone who turns out to be a maniac. In Russia at the moment there is a simple denial of reality. Many Russians flatly refuse to believe that this is a real war with real cities getting really destroyed.

Both my mother and my mother-in-law fall into this pattern. They’re against the war – everyone is ‘against’ it, of course – but don’t have the guts to acknowledge it’s happening on the scale it is. All the videos of blown-up buildings are fakes, they say. They simply can’t accept a world in which all this is happening, and I can’t bring myself to destroy their cosy view of life. So I avoid talking to them about it completely, feeling sorry for their fragile self-deception.

But they’re aided by the Russian authorities, who have cut off all independent media and so help people to cling onto this reality. It’s a world in which Russia never attacks any country, its wars are always defensive, and the Russian soldier is always a liberator. ‘Why do these small nations turn against us? After all we were only ever kind to them, giving them our help and protection.’ Only a huge shock, something like the Germans experienced in 1945, could ever shatter this view. But even for the Germans it took many decades to come to terms with it.

This isn’t true of all Russians, of course. There’s always a percentage of people immune to propaganda and ready to protest, but the price of such protest is so high and the potential outcome so negligible, there seems little point. There aren’t so many people willing to be jailed just to show they’re against Putin and his government.

‘Why don’t you kick Putin out?’ the Ukrainians demand of us, as if it were all so simple. ‘We did it with Viktor Yanukovych in 2014.’ But the Yanukovych regime was a lot less ready to apply brute force. Putin, meanwhile, has been preparing for this day for decades. He has thousands of well-paid enforcers ready to nip any protest in the bud. In 2020, several months of active street protests in Belarus – involving a good share of Belarus’s population – failed completely to topple the regime. Russians observed this and came to a conclusion. In Russia it’s even less likely.

So what do you do if you can’t accept the media’s version of reality yet can’t do anything to oppose it? You can leave. But that’s not so simple either. I love my home and I love my parents. They definitely won’t move abroad, so it will break my heart to abandon them. And even if I sold my apartment and my car it wouldn’t help much. New laws prevent me taking anything more than $10,000 (£7,500) across the border. With the rouble plummeting in value, everything I own has become, in the space of three weeks, worth about half as much. I must also face the fact I don’t really have anywhere to go. There are no friends or relatives abroad that could help us find jobs or lodgings.

I foresee a life of wandering from one country to another, not wanted anywhere. In the world’s eyes, Ukrainians are heroes and the victims of non-provoked aggression. Russians are either war-supporters or craven conformists. All these things matter when I think of changing my country.

There may come a day when it won’t be a matter of choice anymore, but a matter of life and death. All I can do now is prepare for this moment, and hope by then it won’t be too late. It’s as the song from my youth by the Clash put it: ‘If I go it will be trouble. If I stay it will be double.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in