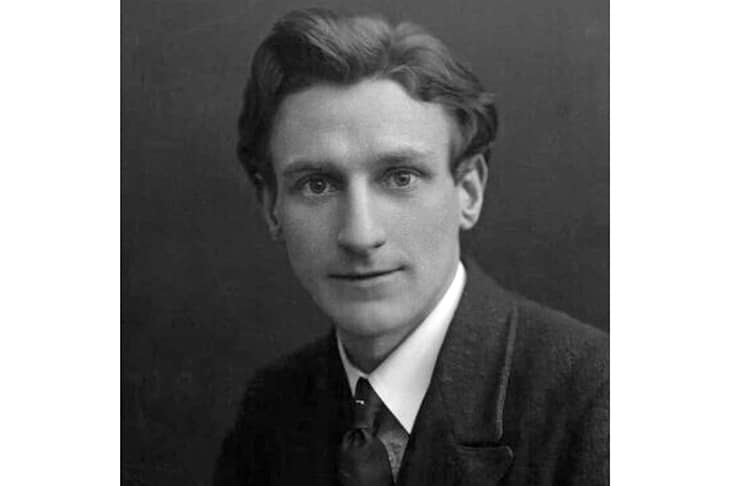

Harley Granville-Barker, actor, director, playwright, manager and critic, was a pasha of the Edwardian London stage. As a director, his Midsummer Night’s Dream of 1914 was a theatrical landmark. His own plays were provocative and controversial. The Secret Life, for example, was an analysis of the torpor of the British ruling classes. Waste, involving a married woman’s lethal abortion, was suppressed by the Lord Chamberlain. In 1916, aged 38, at the peak of his celebrity, the great Harley Granville-Barker volunteered for a walk-on part on the Western Front as a Red Cross auxiliary.

Last week I came across an account of his opening night in the trenches, as related to a military doctor, Dr Harold Dearden, and repeated in that man’s riveting Great War diaries, published in 1928 under the title Medicine and Duty.

As London’s leading luvvie entered the darkened front-line trench (reports Dr Dearden’s informant) he was so frightened that as he progressed along it his knuckles beat a tattoo against the wooden sides. Such palpable fear was noticed by the soldiers in residence and Granville-Barker was ‘ragged mercilessly’ for it. Some wag then suggested that the best way for a new chap like him to overcome his fear was to loose off a machine gun at the German trench opposite ‘to get your eye in’. After ‘much persuasion’ the author of the seminal Prefaces to Shakespeare (still used in schools in my day) elected instead to fire a service revolver across no-man’s-land, a single revolver shot being less likely to draw immediate retaliation from the Alley Man. Instead of a revolver, however, a small pistol used to send up incandescent, slowly descending Verey lights was placed in his trembling hand and in the darkness he was hoisted up on to the trench parapet and told to let the thing off. Which he did, turning night to instant day, revealing in close, vivid detail the British trench, no-man’s-land, the German front-line trench 50 yards away and featuring Harley Granville-Barker frozen glamorously on the trench parapet as if seared in the limelights of the Royal Court.

As soon as he saw where he was, he fell down into the trench and lay paralysed with fear in the foetal position for an hour, finally crawling into the nearest dugout where he remained until daylight. The informant added that the lads ‘got into the devil of a row with the CO for it’, but ‘it must have been a priceless affair while it lasted’.

I don’t watch telly — we ain’t got one. I haven’t read a novel for while and lately I’ve stopped reading even the papers. I guess I’m tired of it all or maybe just depressed. And seen first thing in the morning a headline like ‘Sussexes join Spotify row’ only lowers the spirit still further. Instead I read obsessively about the Great War, and for occasional relief Thomas Hardy, the poet who poet officers such as Sassoon and Blunden took to that war in their knapsacks. Sheer reactionary nostalgia on my part — I freely admit it — for an England that I don’t suppose for a moment existed except in The Wind in the Willows or A.E. Housman. But the tragedy of the largest volunteer army in history so casually expended is real and poignant enough. And for me, today, what happened to the nation in France and Belgium 100 years ago still feels like the main news headlines.

And now that it’s too late, how I wish I could have talked with a little understanding to some of those who volunteered and went out. As a child I was taken once to the Royal Hospital in Chelsea. A friend of my mother had a relative there. I remember my astonishment at the spry, childlike old man who bent and urged me to feel the definite, alarming depression in his skull inflicted by a German rifle butt in hand-to-hand trench fighting.

Then I lived for a while with a man who had been a naval cadet at the battle of Jutland. ‘What was it like, Commander?’ I’d say. But he couldn’t really remember. He would characterise his experience of that gigantic naval engagement in the vaguest of terms, either as ‘most extraordinary’ or ‘a perfect nuisance’.

And my grandfather, it was thought, had fought with the Machine Gun Corps at Ypres, was wounded there, and carried a piece of shrapnel in his leg for the rest of his life. But he never spoke about his leg, or about the war, or indeed about the past, and was too formidable an individual to be detained by ‘damned silly’ questions. And he’s been dead now 50 years.

So the old memoirs and the poetry are all I have to go on. And given, in my case, an increasingly urgent choice between, say, Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War and this morning’s headline, ‘Glitterati go on Hollywood land grab’, it’s really no contest.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in