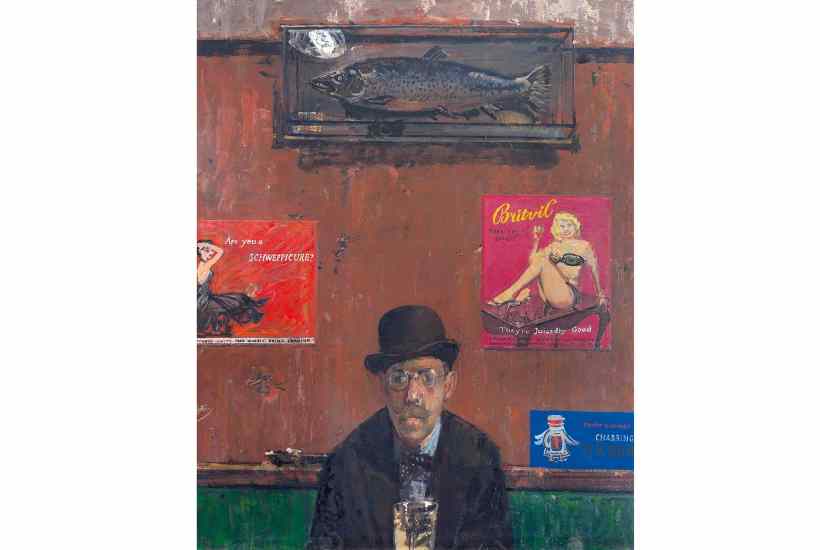

Where do you see paintings by Ruskin Spear (1911–90)? In the salerooms mostly, because his work in public collections is rarely on display. Until the National Portrait Gallery closed for redevelopment it was, however, possible to study Spear’s splendid portrait of ‘Citizen James’ (Sid James) peering from a black and white TV screen, and his oil sketch of Harold Wilson wreathed in pipe smoke, the epitome of political cunning.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Tanya Harrod’s Humankind: Ruskin Spear, class, culture and art in 20th-century Britain is published by Thames & Hudson.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in