I spend a lot of my life worrying about the climate. When you have more than 100 miles of precious chalk streams under your care, rain becomes the currency of your life. Too much in summer. Too little in winter. Or sometimes the other way around. Other times a bit of both. For us river folk, as for farmers, the weather is never quite right.

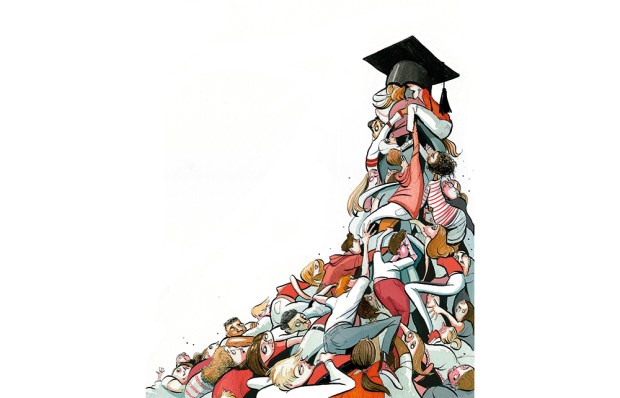

Who do I blame when it is not quite right? Well, mostly us. People. Society. Urbanisation. Too many people sucking too much water from too few rivers. Water companies pumping untreated sewage into already critically depleted rivers. Politicians who allow the building of houses on floodplains. Agriculture that gets a free pass to plough, plant and spray pretty much whatever it likes in sensitive river catchments. Do I blame climate change? Not in my darkest moments, no.

Now, I’m no climate change denier — we are daily trashing our planet in a bold bid for human oblivion — but to use a global problem as an excuse for locally sourced destruction is delusional. We have the same water we have always had: the British rainfall total for 2021 will be much the same as it was for 1921, which was much the same as for 1821. At my home, which happens to be a water mill, the wheel still works as efficiently and effectively as when it was updated from wood to cast iron in 1865.

Of course, the counter-argument to this is that British weather is more unpredictable today. We have the right rain but increasingly at the wrong times. Or so it is said. But that is old news. Henry Rider Haggard, of King Solomon’s Mines fame, became a farmer in the later years of his Victorian life, bewailing in his agricultural chronicles wet summers and dry winters, all in sage agreement with his Norfolk neighbours that the climate was irreversibly changing.

I don’t know why it is, but for some reason there seems to be an expectation that British weather should behave as if directed by some super-algorithm that will provide all the weather, at all the times, exactly as we wish it to be. I have this strange paperback book I unearthed when clearing out the house of my late mother. It is not so old, 1993, but it charts the freak weather of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight dating back to 1600.

Here are a few highlights: it rained every day on the Isle of Wight in August 1648, ruining the harvest; in 1703 a tempest in the Solent claimed 8,000 lives; the naturalist Gilbert White recorded the coldest ever day in 1776; a tornado struck Portsmouth in 1810; in 1859 a severe and unexpected October frost caused the mangolds, turnips and swedes to rot; some 22 inches of snow fell in a single day in north Hampshire in 1908; in 1929, generally considered a freakish year, after 136 consecutive days without rain, the water board implemented a hosepipe ban for gardens and motor cars. Sound familiar?

Given that The Hampshire and Isle of Wight Weather Book by Mark Davison, Ian Currie and Bob Ogley runs to 167 pages, I could go on and on. But you are probably getting the idea. And, remember, this is just one relatively weather-benign southern county of England. Yet despite that, the home of the Royal Navy and birthplace of Charles Dickens has a history of notable weather events that would make national — and possibly international — headlines, if repeated today.

The truth is, it is not the climate, it is us. Our expectations are absurd. Snow at Christmas. Bank Holiday scorchers. The perfect wedding day. Over these we lay our massive immolation of the countryside. But guess what? If you build homes in a floodplain, they will at some point flood. If you suck dry the springs that feed a river, it will dry up in summer. If you pollute a river, it — and all that live in it — will die. There is barely any part of Britain that is escaping the predations of what we currently consider the acceptable face of local use and progress.

Yes, we need to save the planet — but first we need to save that tiny bit within which we all live.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in