Diamonds are forever, they say. Likewise, brilliant games of chess have an everlasting sparkle. I will never tire of replaying the combination from Steinitz–von Bardeleben, Hastings 1895. So I’m a huge fan of tournaments which award brilliancy prizes, in recognition of these achievements.

Fide recently organised an Online Olympiad for People with Disabilities. This excellent initiative was a reminder that the game is uniquely accessible, and saw 61 teams competing from 45 different countries. Many players overcame significant physical obstacles in order to take part.

Vladimir Trkaljanov, who is visually impaired, was awarded the Gazprom Brilliancy prize, his game singled out from the shortlist by six out of 13 international judges. At move 12, he presents his opponent with an irresistible temptation — the pawn on e5 says ‘Take me’. And so she does, only to be swept into an inexorable sequence, which ends, a dozen moves later, in White’s favour, after the sacrifice of a whole rook. It is a coruscating combination.

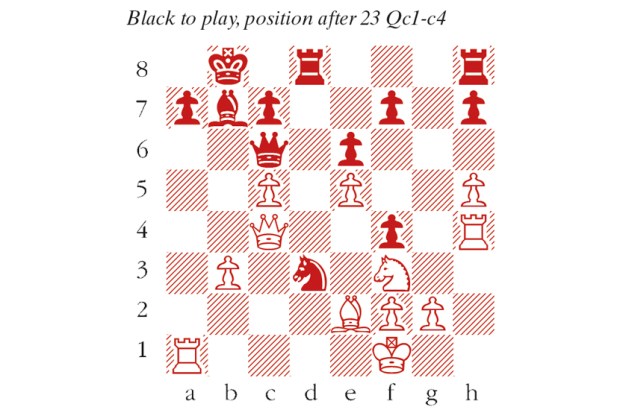

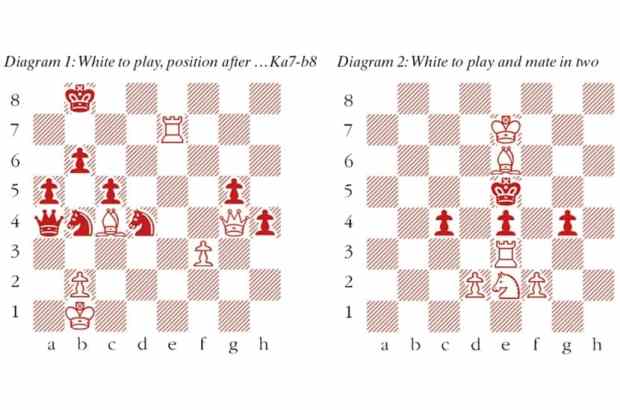

But here’s the catch: a close inspection of my database reveals that almost the entire game has been played before, right up to move 26. The game Kalegin–Katzir, from 2010, saw 26…Kg6, and Black resigned after 27 Qg3+. The position in the diagram has occurred at least seven times before, with White winning every time. It is, in essence, one of the most elaborate opening traps I have ever seen.

For practical purposes, Trkaljanov’s play was faultless, and anyone should be proud of such a game. But it is a fair guess (though I do not know) that it was the product of erudition rather than inspiration. Indeed, that strikes me as even more enviable than a happy accident of rediscovery. When a game is so radiant, does it matter whether it was made in the lab or prised from the pit? Decide for yourself:

Vladimir Trkaljanov (North Macedonia) –

Irina Ostry (Kyrgyzstan)

Fide Online Olympiad for People with Disabilities, November 2020

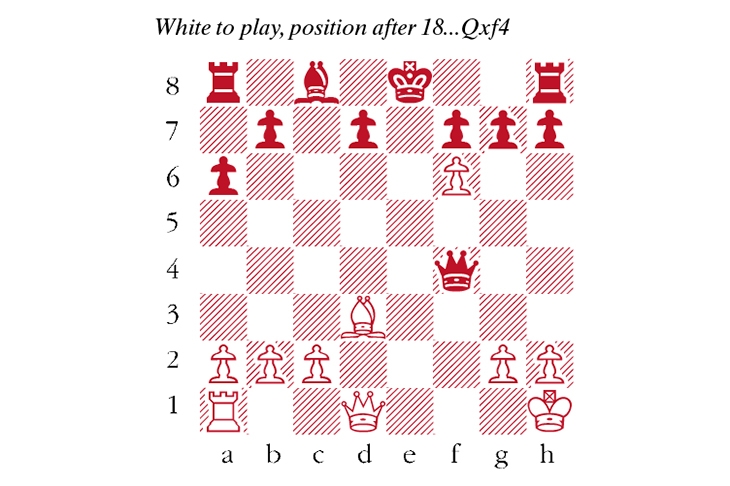

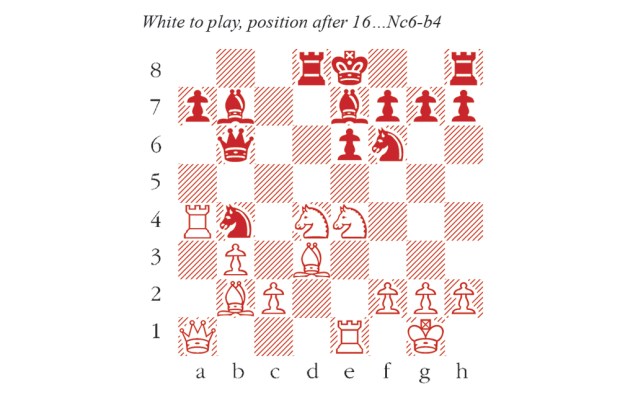

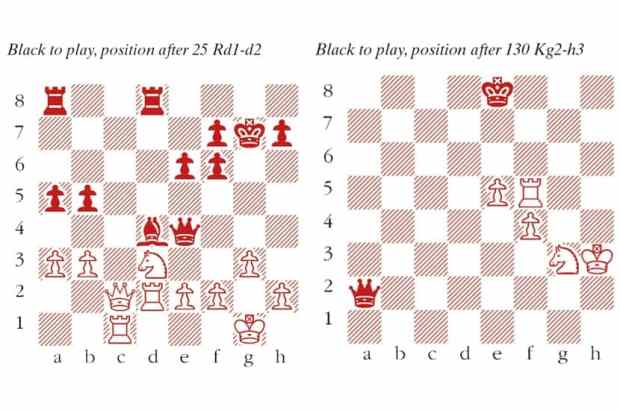

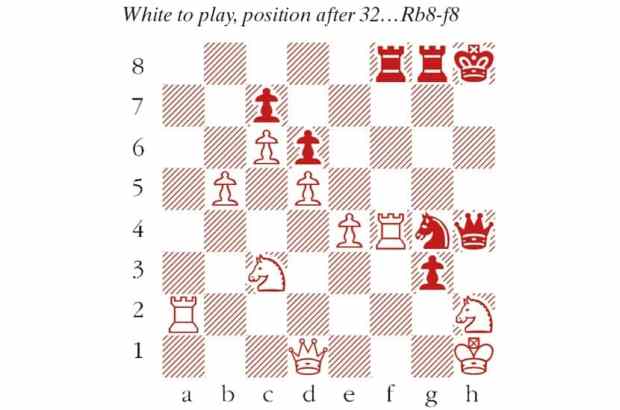

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 a6 5 Nc3 Qc7 6 Bd3 Nf6 7 O-O Nc6 8 Be3 Ne5 9 f4 Neg4 10 Bd2 Bc5 11 Ne2 e5 12 fxe5 Qxe5 What could be more natural? This attacks the knight on d4 and threatens Qxh2 mate. But 12…d5! was preferable (albeit complex), and may promise a small edge, since 13 exf6 allows mate on h2. Thus, 9 h3 was an improvement for White. 13 Bf4 Bxd4+ 14 Kh1 Qc5 15 Nxd4 Qxd4 A piece down, White urgently needs counterplay. 16 e5! A powerful advance, as the knight on f6 is yoked to its ally on g4. Black would love to give back the extra piece to complete her development, but 16…O-O 17 Bxh7+, or 16…d5 17 Bb5+ both win the queen on d4. 16…Nf2+ Winning material, but deepening the trouble. The lesser evil was 16…Nxe5 17 Bxe5 Qxe5 18 Re1 d6 19 Rxe5 dxe5 20 Qe2 O-O 21 Qxe5. With rook and knight for queen, Black could still offer stubborn resistance. 17 Rxf2 Qxf2 18 exf6 Qxf4 (see diagram) 18…O-O 19 Bxh7+! Kxh7 20 Qh5+ Kg8 21 Qg5 g6 22 Qh6 with Qg7 mate to follow. 19 Qe1+! This deft sidestep, setting up a ricochet off the a-file, is much more effective than 19 Qe2+. 19…Kd8 20 fxg7 Rg8 21 Qa5+ Ke7 21…Qc7 22 Qg5+ Ke8 23 Re1+ and mate next move. 22 Re1+ Kf6 23 Qc3+ Kg5 24 Rf1 Qxf1+ 25 Bxf1 Normally, two rooks can put up a fight against queen and pawn. But here, Black’s exposed king cannot last long. 25…d5 26 h4+ Kxh4 27 Qf6+ Kg3 28 Kg1 Be6 29 Be2 h5 30 Qf2 mate An elegant finish.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in