I met Jane Birkin’s parents, who flit across these pages. Her mother, Judy Campbell, was an actress in Noël Coward plays and

a cabaret singer who’d worked with Charles Hawtrey, and when I invited her to a party once she drove her Mini up the steps and into the hotel lobby. Jane’s father, David, had a good war, his boat picking up pilots and spies hidden by the Resistance on the Breton coast. He told me ’Allo ’Allowasn’t a comedy, it was documentary realism. He endured many operations on his optic nerve. A piece of hip bone was grafted to his eye socket. His lungs, as Jane says, were weakened by ‘too many anaesthetics’.

The Birkin fortune came from Nottingham lace. There were aristocrats (the Russells) in the background. Jane therefore spent a very comfortable childhood, in big houses with lawns and tennis courts, and, as is clear from Munkey Diaries (Munkey being her toy monkey to whom private thoughts were confided), deprivation has never been on the agenda. The book begins with idyllic Enid Blyton school-days depictions — dorm feasts of sausage, Spam, greengages and Coca-Cola; birthday parties (‘wonderful fun’) with bridge rolls and lemon squash — and then the bulk of it unfolds in grand hotels in Venice and Deauville, or in the Paris apartment block where Edith Piaf died and her corpse was put on show.

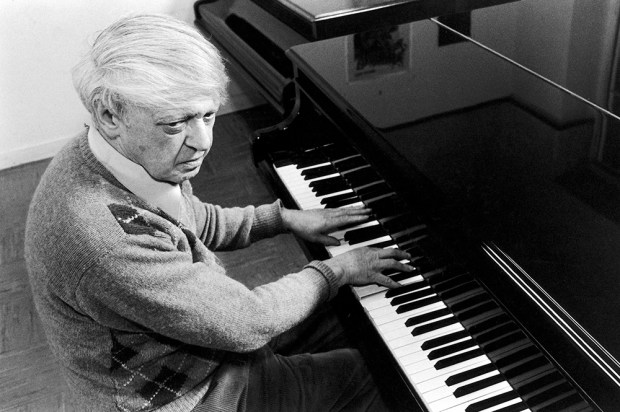

Nevertheless, despite the posh bohemianism — chateaux holidays, and speeding around Paris in a taxi with her legs sticking out of the window — Jane does not seem happy. Indeed, this book is lachrymose to the point of sogginess. ‘The loo is the only quiet place to cry,’ she says of school. ‘I have fits of depression where I cry and am told to grow up.’ It must have been very disconcerting to be followed about always by lots of creepy older men — Jane was unaware of how pretty she’d become. Arthur Rubinstein touched her up as if her thigh were a piano keyboard.

In 1963, aged 17, Jane was swept off her feet by the 32-year-old John Barry, the composer of film scores. They were married as soon as she was of age, and it is painful to see how callously Barry treated her, immediately openly philandering: ‘You don’t want me to lie, do you?’ he replied when Jane enquired about the womanising. ‘I felt like crying every moment,’ she says. ‘I am beginning to hate him. I hate his selfishness.’ There was a child, Kate, born in 1967, in whom Barry showed no interest, and who was to leap from a window to her death in 2013.

They were divorced. Though Barry gave Jane a house in Cheyne Row, she used it only at Christmas. Instead, having won a tiny role in Blow Up (‘I burst into tears’ before Antonioni at the audition), she moved to Paris to be a film star, appearing in dozens of continental pictures none will have heard of. She also recorded the notorious ‘Je t’aime… moi non plus’ with Serge Gainsbourg — ‘the sexiest song in the world,’ says Jane. But is it? Possibly the French can take the heavy breathing and whispering seriously and find some deep erotic philosophy in the gurgling and sighing. To these ears it is not a patch on Bernard Bresslaw’s classic ‘Mad Passionate Love,’ with its lyrics about people ‘doing their wooing’.

The French have little sense of the inadvertently ridiculous, and nor did Jane, for she quite fell for Serge, who only occasionally washed his dirty feet in the bidet. He was moody and sarcastic, and after a heart attack chainsmoked even in the ambulance. (He died in 1991, aged 62.) He is so gentle and soft and then so strong, Jane gushes. ‘I am emotionally completely tied to Serge.’ His way of expressing devotion was tobe violent: ‘He bashed me again and tore me down by my hair and slapped me.’ This is all evidence, of course, of his Gallic integrity, ‘a camouflage for extraordinary shyness’. He also always opened Jane’s private letters.

The relationship maunderings I could have done mostly without, the acres of print where Jane is ‘sentimental and hysterical and weeping’. What I did much enjoy were her critical observations, when she looks beyond her pampered world of nannies, maids and supper at Maxim’s to Yul Brynner and Gina Lollobrigida in some biblical romp: ‘She looked wonderful when she was being stoned. She was wearing light blue against a yellow gold stone’; The Alamo: ‘Too bloodthirsty and too much tomato ketchup’;

Death in Venice: ‘Too much panting and lusting’. Jane made two Agatha Christie films with Maggie Smith, who is quoted as saying: ‘I’m only doing this for the cash… I haven’t even read the script.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in