Spontaneous political uprisings are rare, especially in countries like Australia, but ex-PM Malcolm Turnbull’s bitter memoir reminds me that one did take place – and it will never make it into the history books because it passed almost unreported.

The scene was late November 2009; on Tuesday 24, then-Liberal leader Turnbull had rammed his carbon reduction scheme through a deeply divided party room, and emerged claiming (mischievously) party room support. Early the next morning my husband, then-Liberal Senate Leader Nick Minchin, rang home to say that MPs’ phones were melting down with an extraordinary backlash from the party faithful; not just a few offices either, but across the board. I could hear the surprise and awe in his voice. I had reported politics for the Age in the Canberra gallery, but neither of us had ever seen anything like it. This was a genuine grassroots mass moment yet the media pack could not have been less interested. In their view Turnbull was on the side of the angels and his opponents were Neanderthal climate deniers, so not for the first (or last) time, the groupthink gallery missed a real story. Later that day my husband resigned from the frontbench. The following week Turnbull lost the leadership first time around.

The man in the street tends to get involved in politics only when things are dire. If the place is passably well run, most people will put up with a lot and get on with their own lives, sensibly so. Widespread political activism is actually a bad sign, a sign of trouble. And so it is now, in times of crisis like this, that politics and especially coronavirus politics is on everyone’s lips, and political attitudes seem to be hardening. A Pew survey some days ago found that two-thirds of Americans now had an unfavourable view of China, up over 20 per cent since Trump’s election and now in record negative territory. A Lowy Institute poll last year found a similar 20 per cent negative swing in Australia, with only 32 per cent of Australians trusting China to act responsibly. Add in the pandemic and watch that figure, already a huge shift, plunge even more. India’s leader Modi recently tightened controls against Chinese investment; over a dozen countries are having to dump defective Chinese coronavirus tests and equipment; and in Africa anger is growing over debt relief and reports of Chinese domestic racism against Africans.

This was borne out at my new chiropractor’s last week. She is not only formidably well-informed, but full of passion about it. I asked her what people were saying. ‘Well, they’re not buying anything Chinese anymore,’ she said. Who was saying that? ‘All of them. Everyone!’ she said. I told this story to a business mate subsequently and he laughed, then explained why. He’d been selling medical equipment to small business people in a capital city recently. He had both Russian and Chinese gear and the Chinese gear was one-fifth cheaper. Of the score of business owners he contacted, not one had bought the Chinese equipment – ‘on principle’. He still can’t move it.

Arguably, the virus crisis has ripped the scab off the festering sore of CCP perfidy; an end to daily life as we know it, upwards of 200,000 deaths globally and cratering the world economy will do that. China’s tyranny and totalitarian cruelty have forced themselves into the life of the average Joe and it is hard to see it ending in anything other than a giant global backlash against China. Obviously, we are talking here about the CCP, and not the Chinese people, who are themselves the prime victims of this evil regime.

It seems the man in the street is noticing that China lied about the outbreak of the contagion, suppressed dissent and instead acted to profit from the looming plague, hoarding supplies and profiteering from resale. The man in the street may not be well-informed about the horrors of organ harvesting or the lockup of a million Uighurs, but he has noticed the bat soup narrative, as jokes across Twitter testify. And plenty now know that when China on 23 January locked down Wuhan and stopped its citizens from travelling in China, they were nonetheless allowed to take their infection with them into the West – death ‘ambassadors’ as Rudy Guiliani called them. That act is not quite as vile as Mongols catapulting plague victims into walled cities to spread the Black Death, but it is not far short. It bespeaks a depraved indifference to human life that is shocking to Western sensibilities.

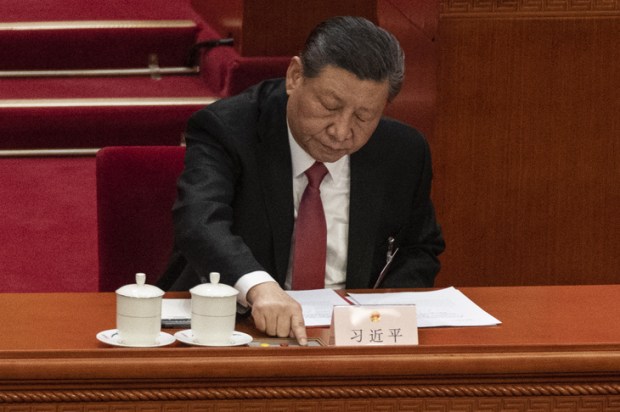

China’s behaviour has been so brazen and in-your-face as to be mystifying. What happened to sending out a warning, Xi? What about an apology, Xi? Instead, Chinese diplomats have attacked our belated attempts to protect ourselves with travel bans. Nor do they see that we have any right to know how and why the virus arose and they are protecting their apologist, the World Health Organisation, cancelling a G20 meeting recently when the US wanted to put an investigation into the WHO on the agenda. Once public attitudes become established, they can be extremely hard to shift. How long did it take for Germany to escape the stain of Nazism once the world realised what had gone on in the concentration camps? The Chinese are anything but stupid; don’t they know how badly this bullying self-righteousness plays in the West?

The eminent geopolitical strategist Dr Edward Luttwak, the ‘Machiavelli of Maryland’ and adviser to US presidents, solved this puzzle for me. He argues that China is so big, so complex, so populous and so much the centre of its own world that it is effectively autistic – his term. Foreign affairs in China is a matter of tributary states arriving in delegations and tugging the forelock, not, as it is for other nations, a matter of advancing interests abroad through argument and alliances. Like the archetypal solo child in families, China is self-centred, and sees no need to change its behaviour.

When China joined the WTO in 2001, conventional wisdom argued that free trade would lead to liberalisation, creating a more democratic China over time. Not only was this wrong, but the reverse happened; China’s economic strength, far from generating freedom within China, has allowed it to export unfreedom abroad. Witness Google working with China to build a censored browser called Dragonfly; witness the NBA’s refusal to support the free speech rights of a Houston Rockets official backing protesters in Hong Kong. Moreover, China’s equivalent of the Berlin Wall, its internet firewall, has allowed it to achieve an unprecedented level of social control domestically, preventing any Western freedoms from taking root.

My eldest son when he was in primary school once gushed about his favourite teacher: ‘And he blames us really well!’

In this case, that means holding the Chinese communist party to account, rather than the Chinese people.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in