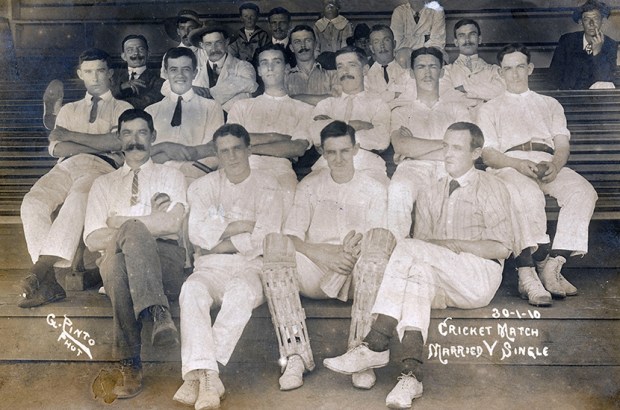

Imagine an archetypal English scene and it’s likely you’re picturing somewhere rural. Despite losing fields and fields each year to developers, the countryside is ingrained in our collective consciousness as our unspoiled national haven. It is Albion’s Garden of Eden, with its Holy Trinity of village church, local pub and cricket ground.

Englishness itself, as much as cricket, is the main theme of Michael Henderson’s genre-melding

And That Will Be England Gone: The Last Summer of Cricket. The title alludes to Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Going, Going’, and the last summer was 2019, when Henderson, sportswriter and cultural critic, took a journey around the cricket grounds of his past.

The international summer was glorious: England won the World Cup at Lord’s (on a typically incomprehensible technicality) and drew a thrilling Ashes series. But now the sport is on the brink of a defining moment. In a few months’ time — national health permitting — the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) is launching a new competition into an already packed schedule. It’s a jazzed-up, short form of the game called The Hundred, and is aimed at the non-cricketing public. It could have come straight out of an ECB version of W1A.

The plan is to arrest an alarming slide in the popularity of cricket amongst the young. ‘Cricket, the game of summer,’ writes Henderson, ‘is now ranked the eighth most popular sport in English secondary schools, behind football, rugby, swimming, athletics and — this takes some believing — basketball, netball and rounders.’

The problem, then, is real. But there’s a chance the ECB’s proposal will kill traditional cricket — and with it, Henderson implies, Englishness itself. Furthermore, The Hundred will symbolically mark the moment when cricket becomes urban rather than rural. For instead of the shires, the teams in The Hundred will represent cities; instead of the whole of Lancashire, they will bear the name of Manchester. In cricketing terms, it’s the final step of the industrial revolution. The Arcadian image of England will be gone.

Henderson’s prognosis is possible, yet without the blood money from The Hundred, many of the professional county cricket clubs are unlikely to survive. And where would county cricket — and thus Englishness — be without Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Gloucestershire? But if the pact is Faustian, how long will it be before Mephistopheles comes for English cricket’s soul?

Henderson is quick to criticise today’s cricketing bureaucrats, and he doesn’t spare the failings of two redoubtably English prime ministers — Thatcher and Major (the latter a big cricket fan) — who oversaw the loss of more than 10,000 school playing fields. The Fall of Albion’s green and pleasant land — and of its most evocative pastime — is not a recent phenomenon.

Sometimes, however, the author doth protest too much. He calls a high-scoring Twenty20 match between Leicestershire and Yorkshire a ‘jamboree’ — an excellent description — but writes: ‘No player could have taken pleasure in his part.’ What about the 24-year-old Tom Kohler-Cadmore who scored 96 not out and who, by Henderson’s admission, ‘played a couple of strokes that would have graced a proper game’? Twenty20 may lack the plot and unfolding narrative of a test match — and especially of a five-match series — but the skills and athleticism of the best T20 players are remarkable. Just as readers can enjoy long novels, novellas or short stories, the cricket lover can find quality in any form.

Henderson’s book is not all doom-saying. Nor is it pure nostalgia for the age of Fred Trueman and Geoffrey Boycott. Tales from the press box at Derby could furnish an after-dinner speech; and like Test Match Special at its best, or a fine day at Lord’s, part of the fun comes from the detours in conversation. And there are plenty of them, from Ramsbottom’s role in the genesis of Nicholas Nickleby to Vienna and the grave of Schubert. Like the imperial city, Henderson can be baroque: the word ‘amanuensis’ crops up twice in the first 13 pages.

But in an age when so much is dumbed down, it’s a welcome change. Not that all the fancy stuff gets in the way of the narrative. On the contrary, it’s extremely readable. Henderson’s curmudgeonly persona is often amusing, as he takes aim at the ‘craft ale’ bar at Trent Bridge (his inverted commas) and excoriates John Lennon for posing as a working-class hero.

And That Will be England Gone is part memoir, part sports book, part essay. In tone it’s a strange thing: a level-headed lament. Given that this may be a summer without leather and willow, and that coughing has become taboo, Henderson’s book provides a much-needed literary-cricketing alternative: a beautiful clearing of the throat.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in