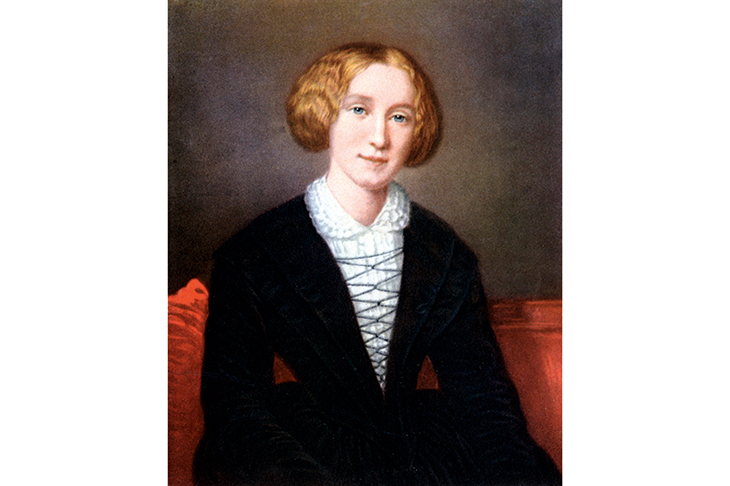

It’s easy to forget, as we celebrate the 200th anniversary of her birth, how radical George Eliot actually was. The face that smiles tenderly out at us from François d’Albert-Durade’s portrait (pictured), on the dust jacket of her books, seems to epitomise the moralising Victorians — very establishment. And perhaps this is why her dramatic and shocking life story is so oddly absent from the English public imagination.

How radical was she? ‘May I unceasingly aspire to unclothe all around me of its conventional, human, temporary dress, to look at it in its essence and in its relation to eternity…’

This is an early letter from Marian Evans, or Mary Ann Evans as she was then (she changed her name repeatedly); the provincial girl in Warwickshire, before she met the Coventry sophisticates who changed her life. But what a vow! You can sense her longing for intellectual exploration, and her ambition, too. She was intensely religious, but aged 21 she stopped believing in God. Overnight she refused to go to church any more — witness already the powerful convictions and self that would not fit with authority, in this case the male authority of her father. There was a public row and her father threatened to evict her from the house. Over time a compromise was reached (she would go to church but think her private free thoughts). At the age of 25 she translated David Strauss’s Das Leben Jesuinto English, a radical text that deconstructed Christianity as historical myth.

But the shocking event that defined her image for decades was her decision to live openly with the married George Henry Lewes, who was legally unable to divorce. Society closed its doors instantly, women stopped visiting her, her family broke off contact with her for 25 years. And what of her fiction, that rescued her from her ostracised existence, winning her fame and glory? She’d had enough of cosy bucolic representations of the rural poor as pretty people with flushed faces sleeping in haystacks; so her early Scenes of Clerical Lifefeatures an alcoholic wife-beater; in Adam Bedea unmarried young woman murders her baby. The choice of subject isn’t cosy. In the later Middlemarchthe subject matter is less controversial but the instinct to question is still there. Dorothea famously wants to do something with her life, but look closer, and the same questions are being asked at a micro-level. Consoling in tone, those famous authorial addresses to the reader are also mind-expanding. It’s a reflex she can’t resist.

Here’s one on James Chettam’s attitude to Dorothea in Middlemarch: ‘Sir James had no idea that he should ever like to put down the predominance of this handsome girl, in whose cleverness he delighted. Why not? A man’s mind — what there is of it — has always the advantage of being masculine — as the smallest birch-tree is of a higher kind than the most soaring palm — and even his ignorance is of a sounder quality.’ With gentle irony Eliot satirises the received wisdom about men’s minds, and the reader scarcely notices she’s done it.

What did she think about women in her own time? Here her stance becomes fascinating and controversial. She was herself bolder than almost all her contemporaries in terms of what she had done — she had walked the walk, with extraordinary daring. But she did not talk the feminist talk of her age, and saw women’s power to nurture as precious. Of course there was a contradiction here, between her views and her own life — she was a childless, immensely ambitious and successful genius. It’s a contradiction that won’t resolve. But her work remains her best mouthpiece.

Her novels repeatedly and brilliantly diagnose the brutal limitations placed on women’s lives, from Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Flossto Dorothea in Middlemarch— clever women full of hopes and desires, frustrated by the world they inhabit. The late, greatDaniel Derondais the most feminist of all her works. Eliot may have named the book after the hero, but it’s the heroine who steals the show. Gwendolen is a breathtakingly original and strange creation (what other heroine in a 19th–century novel strangles her sister’s canary as a girl?), a product of both parental over-indulgence, and the sphere in which young girls become ‘accomplished’ in preparation for marriage. Precariously dependent on admiration for her happiness, she is an egotist without direction, marooned by her narcissism. She’s scary. When her family lose their money, she’s left with ‘accomplishments’ only, without agency in the real world. What follows is marriage to Grandcourt, one of the most hideous in the whole of Victorian fiction — subordination to a sadist whose purpose is control.

Eliot kept moving in her thinking. She saw the limitations of life for women, wrote better about them than almost anyone. But like some jack-in-the-box, if you try to push her into a position, she’ll spring back with a view that doesn’t fit. Reality and life were always more complicated for her than a set of ideas, or alliances. Her rejection of religion says it all. She rowed with her father; later regretted the row as egotistical and insensitive on her own part. She appreciated, deeply, the spiritual needs that were parent to religion. At the end of her life, the controversial figure who had lived unwed for 24 years with George Henry Lewes, married, after Lewes’s demise, a younger man rather rapidly — 20 years younger. What’s more, they married in a church.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in