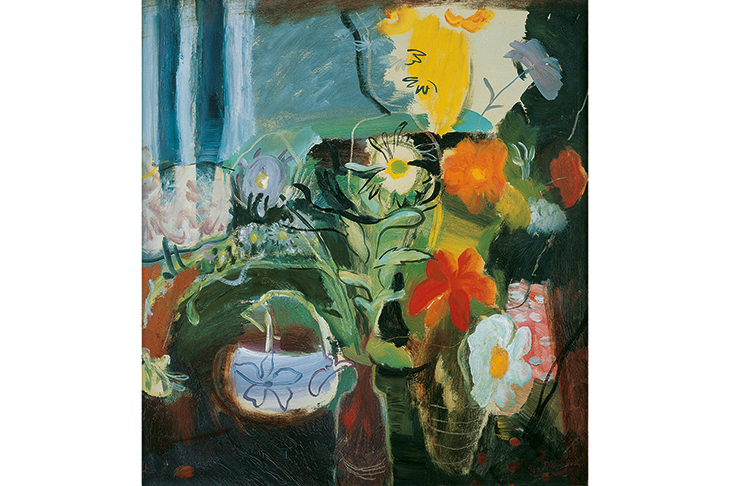

Set down the secateurs, silence the strimmers. Let it grow, let it grow, let it grow. Ivon Hitchens was a painter of hedgerow and undergrowth, bracken and bramble. Whoosh! go his seedlings, sprouting, bolting, demanding repotting. The first Hitchens you see on the wall outside this exhibition at Pallant House is his lithograph ‘Still Life’ (1938).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in