Prime Minister Morrison’s commitment to addressing the escalating rate of suicide is commendable and much needed. Given 3,128 Australians committed suicide in 2017 compared to 2,866 in 2016 and preliminary figures put the figure at over eight suicides per day how to prevent people ending their lives is a crucial issue.

Add the facts that the rate of suicide for men is three times greater than for women and that more young men commit suicide than are killed in road accidents and it’s clear that action must be taken.

On the other hand the PM’s comment ‘One life lost to suicide is one too many, which is why my government is working towards a zero suicide goal’ displays a misunderstanding and an over- reach that needs to be questioned.

Governments can do many things that are essential to people’s safety and ability to lead a productive and rewarding life but when it comes to liberal democracies and a person’s emotional, psychological and spiritual health the state will always play a secondary role.

While government agencies and mental health services can seek to alleviate and hopefully address the pressures and symptoms that lead to suicide the reality is that if individuals lack the resilience, courage and emotional and psychological maturity and strength to save themselves then suicide rates will only increase.

As argued by Margaret Thatcher when suggesting there are limitations to what the state can achieve, ‘And, you know, there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look to themselves first’.

And while the traditional family is condemned by politically correct feminists and gender activists as misogynist and heteronormative, there’s no denying that a family where there is a mother and a father is crucial to developing the confidence, maturity and resilience to cope with life’s inevitable challenges and pitfalls.

Research cited in Maybe ‘I do’ modern marriage & the pursuit of happiness by federal MP Kevin Andrews concludes, to quote from an Australian report, that individuals prone to suicide are ‘less likely to be living with their biological parents and more likely to be from separated, divorced and single parent families’.

Andrews also refers to European and American research concluding there is a higher risk of suffering depression (one of the factors associated with suicide) among teenagers from single parent families and those with step-parents.

Research in America concludes that young African-American teenagers living in a single parent household where the father is absent are more prone to gang violence, drug abuse and failure at school than those living with two biological parents. It’s also the case that girls suffer a greater incidence of sexual harassment and rape in those families where the biological father has been replaced by a stepfather.

In an increasingly materialistic and narcissistic era, where many argue we are living in a post-Christian age, it also stands to reason that a life without spiritual enrichment and a sense of God’s grace is also one more susceptible to depression and self-harm.

Christianity teaches, notwithstanding this vale of tears, the imperfectability of man and the existence of evil, that there is goodness in the world and that with courage, love and humility it is possible to overcome adversity and to deal with sadness and loss.

As stated by the Christian mystic Julian of Norwich, to accept the presence of God is to know ‘All shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well’. The pain and suffering of this world are transitory and the challenge is to find solace and comfort in a deeper and more lasting sense of why things are as they are.

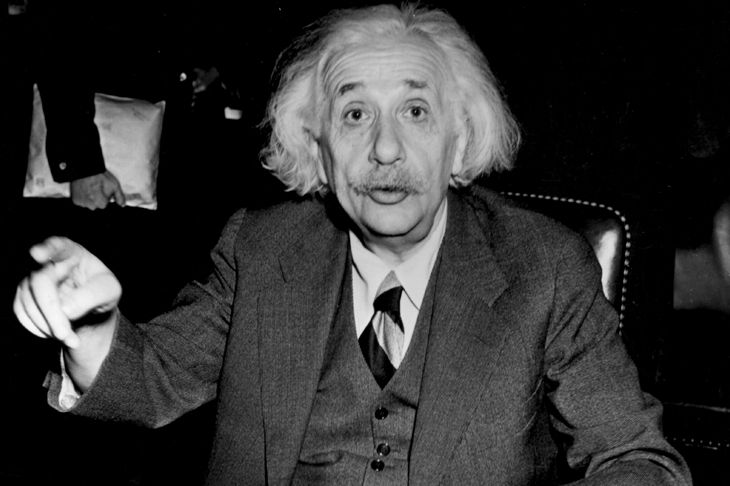

And for those atheists and agnostics who believe this physical world is all there is, it is significant that the physicist Albert Einstein argues ‘the most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is a fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science’.

While admitting he is not an orthodox Jew or Christian, Einstein writes that he is a ‘deeply religious man’ and that a person who either fails or refuses to experience the mysterious and the sublime ‘is as good as dead, and his eyes are dimmed’.

And while much of what currently passes as education is all about being politically correct on the basis that knowledge is a social construct and what students learn has to be critiqued and deconstructed in terms of power relationships, Einstein also points towards a more lasting and deeper sense of meaning.

He writes, ‘The ideals which have lighted my way, and time after time given me new courage to face life cheerfully, have been Kindness, Beauty and Truth’. Virtues increasingly absent at a time when knowledge and wisdom have been reduced to 21st century competencies like gathering information and using digital technologies.

Music, literature, dance and art no longer evoke beauty and truth or as suggested by William Blake cleanse the doors of perception to allow one to see the infinite. Instead, Marxist-inspired critical theory and its rainbow alliance of politically correct offshoots reduce everything to a barren, empty and pointless discourse about power and privilege, identity politics and victimhood.

When discussing the relationship between individuals and government Margaret Thatcher also says, ‘It’s our duty to look after ourselves and then, also to look after our neighbour. People have got the entitlements too much in mind, without the obligations. There’s no such thing as entitlement, unless someone has first met an obligation’.

Contrary to what Prime Minister Scott Morrison implies, the power of the state to reduce suicide is limited. Far better for governments to step back and to acknowledge it is the society and culture at large that teaches resilience, courage and the ability to overcome adversity. Destroy the family, religion and education and it should not surprise that self-harm and suicide increase as individuals are no longer grounded in anything positive, worthwhile or beneficial.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in