Nothing was so interesting to Yves Klein as the void. In 1960 he leapt into it for a photograph — back arched, chin raised, spread-eagled. The same year, he took out a patent for International Klein Blue (IKB), a colour inspired by the limitlessness of the sky itself. He even went so far as to stage an exhibition of white walls and an empty cabinet. If there is a less appropriate place to exhibit his work than the lavishly adorned Blenheim Palace, I can’t think of it.

Klein was born in Nice in 1928 and learned judo as well as art. In his late teens he visited the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua and marvelled at Giotto’s 14th-century frescoes, particularly the ceiling, which was bluer than the deepest seas. When Klein went on to formulate his own colour in the 1950s, he retained the intensity of the pigment by ingeniously combining it with an artificial resin and petroleum rather than simply oil. The result was less a sky blue than a deep ultramarine that might have fallen straight from Giotto’s heaven.

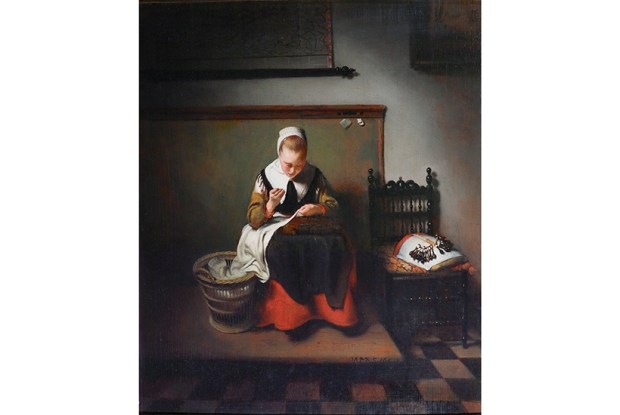

Venus wore it best. Born in the sea and raised to the skies, she became the most iconic model of Klein’s trademarked shade. In the Saloon of Blenheim Palace there are 12 of her, cast from the Venus de Milo and doused in IKB. How incongruous they look. Behind them are 18th-century wall paintings of former statesmen. Above, on the domed ceiling, John Churchill, first Duke of Marlborough, raises his sword during the War of the Spanish Succession while Peace stays his hand. If Klein’s blue Venuses have come to promote love, not war, they are wasting their time. The duke, who received the palace from Queen Anne following his triumph in the Battle of Blenheim, might more usefully have been attended by one of Klein’s figures of the Victory of Samothrace.

The reason each of Klein’s works has been positioned where it has is so open to interpretation in this show that you end up with none. Three tables filled with pigment — rose, gold, IKB — stand on the floor of one of the state rooms beneath a painting of the Duke examining battle plans at a velvet-draped table top. The juxtaposition of old and new fails to illuminate either. Klein’s vibrant conceptual art feels crudely misplaced among the martial scenes. More effective is the display of his cheerful coloured plates amid the Meissen in the china cabinets. The splashes of rose and gold are especially welcome. IKB is marvellous but soon becomes monotonous. So thick and velvety is it that you struggle to distinguish a Klein blue bronze from a Klein blue plaster.

Klein liked to apply colour imperceptibly to the surface, rejecting brushes as ‘too psychological’ in favour of ‘more anonymous’ tools. Naked women writhed in the blue to become ‘living brushes’. Sponges soaked in paint became artworks in themselves. They sit in clusters like coral on the white mantelpiece of his white studio in a photograph from 1959. A few specimens from the ‘Sponge Forest’ share the mantelpiece of one of the Blenheim state rooms with bronzes of Hercules. Another sponge, huge and brain-like, sits on a table beside a bronze of the 10th Duke of Marlborough as a baby. He reaches towards it as though it’s bath time.

The exhibition continues in a gallery beyond the palace. Head here first. There isn’t much art but there are some much-needed explanations of Klein’s methods, and wonderful photographs of him at work and play. Several show his ‘living brushes’ standing Venus-like on plinths or rolling around at the feet of an orchestra. (Klein composed a ‘Monotone Symphony’ consisting of a single chord in D major held for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of silence, to open his Anthropométries exhibition in Paris in 1960.) Living-brush paintings such as ‘Jonathan Swift’, which is sandwiched between the Van Dycks and the Joshua Reynolds in the Red Drawing Room, are slightly less bewildering once you’ve seen the bodies that created them.

It’s only really in this gallery that you appreciate the fun of Klein. Had he not died so young — he was 34 when he suffered a fatal heart attack — he would no doubt have reinvented himself several times over. From this show, billed, incredibly, as the most comprehensive of his work in the UK, he emerges as a visionary and playful young heir to Marcel Duchamp. Given time he might have produced something even more shocking than a urinal for Blenheim’s dining room.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in