A young man in a grey tracksuit and silver mask looks straight at the camera. He is flanked by others in black anoraks, heads jabbed sideways, moving to the beat. The young man raises his hand and curls it into the shape of a gun. ‘Bang, bang, I made the street messy. Bang, bang and I don’t feel sorry for his mum.’

Last year 80 people were stabbed to death in London, a quarter in their teens. Fifty have died already this year. The Met Commissioner, Cressida Dick, deployed 300 extra police at the weekend after six separate knife attacks last week, five of the victims being teenagers, one a 13-year-old boy.

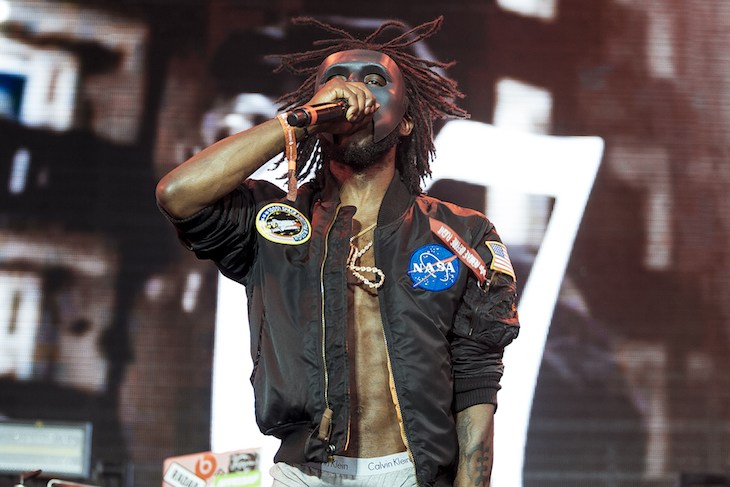

Welcome to the world of UK drill rap — the music behind the explosion of teenage deaths on London’s streets. This is the music that has turned murder into a money–making industry. Understand it and you understand why these children are dying.

A glance at drill videos on YouTube is revealing. Here are no dreams of beautiful women or exotic places. This is a world of shabby London streets, chicken take-aways and dirty stairwells. It centres on London’s various gangs. They display weapons, talk about drug dealing, describe recent stabbings and issue threats to rivals. Their concerns are a bizarre combination of the homicidal and domestic: how to clean trainers soaked in blood or a kitchen knife with bleach. ‘Blood on my skank, keep it, clean it, use hot water and bleach it,’ one rapper instructs would-be assailants. Another video even describes stealing a knife from ‘Mummy’s kitchen’. It is a reminder that these lethal young men and their fans are teenagers still living at home. This is reinforced by their appearance. Every-thing in a drill video is designed to make boys look big and fierce, from the bulk of their jackets to the hoods pulled up over baseball caps. The unguarded glance of a 14-year-old gives the game away. Drillers are schoolboys and still in adult care — or they should be.

The first drill rapper, Chief Keef from Chicago’s south side, was signed up to a multi-million-dollar deal at the age of 16. Lil Mouse, another drill star, was only 13 when he was discovered. Drill soon moved to London. The music and videos serve to unite a disparate group of boys into a gang, give them a beat they can march to, and provide visual imagery to incite young men to violence.

The lure of drill videos and the gang life they glorify is horribly understandable. Apart from the violence, there is little difference between joining a gang and a sports team. Both offer teenage boys what they crave: a challenging activity, competition with their peers that allows them to make friends, prove themselves and win validation from grown-up men. In the absence of an alternative, these teenage boys have created their own version of Lord of the Flies. Our inability to give them what they need to thrive within law-abiding society has consigned a generation to nihilism and bloodshed.

Gang members even keep a scoreboard of their triumphs, all publicised on video. ‘If you are in a gang and one boy has stabbed two people and another’s stabbed nobody, then there is peer pressure to go out and do it,’ says Chris Preddie, a 24-year-old youth worker. Or as one gang member put it to Preddie: ‘Man’s on the score sheet. Pom, pom pom. Dip, dip, dip.’ That boy is top of the table because he has stabbed six people. He does not even know if he has killed them or not. Chris Hobbs, a Met officer who served on the anti-guns Trident team, points out that there are 300-400 non-fatal stabbings a month in London — not all gang-related, but still a staggering score. Young boys are consumed by the closed world of drill videos, with their compelling links between social media and the estates or the streets where they or rival gangs live. They wake in the morning and look for new downloads from their favourite platforms on YouTube, Link Up TV, Press Play and GRM Daily. Then they open Snapchat for the latest on their favourite rappers. Who was caught slipping? Who was cheffed or skanked or rushed the night before? Gossip spreads fast with individuals or gangs gaining or losing credibility.

The scene thrives on teenage volatility. A video of a rapper and his gang issuing a threat to a rival gang can be recorded on Monday, shot and edited by Wednesday, uploaded on Thursday and get more than 100,000 views by the weekend. It leads to an incident or a stabbing and that in turn gets a new rap.

For the fans and the participants, the music is powered by violence. Beneath one video, a fan comments: ‘The beef between 150 (Angel Town gang) and 67 (Brixton Hill gang) is the reason drill music is what it is today.’ Fans discuss whether north or south London produces the best rappers. ‘South London for the music but beef wise, I think north, hands down.’ Rather like sports fans, they demand confrontation and aggression from their idols. One fan looks forward to the summer. Several gang members are due to come out of jail and ‘It will be fun to see how this beef continue,’ he comments, as if at the prospect of a good cricket match.

Teenage rappers earn money from the amount of ‘likes’ their videos receive on YouTube. However it is hard for them to turn that into legitimate success and move on with their lives. Rappers only gain those all-important ‘likes’ as long as they play an active part in ‘road’ life. ‘You can’t just eat off this if you are not authentic,’ explains one gangster to me. A rapper will attack another to prove his authenticity and up his likes. But duck a challenge and he loses respect, likes and his earnings. One rapper ‘valid on the music ting’ falls down because ‘everyone thinks he’s wet on the roads’.

To anyone with experience of teenage boys, this desire to excel is all too familiar. For my son, it was playing rugby. For the boy who showed me around Michaela Community School in Brent, it was learning by heart ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ — all 143 verses. What had prompted this, I asked. He was competing with his friends, he said, and the poem provided the greatest challenge. This 13-year-old is the son of migrants and from one of the poorest boroughs in London. His background and the urge to validate himself is identical to that of the gang members in drill videos. But his school has channelled that instinct to transform his life for the better. He has been saved from dying in a pool of blood by the side of the road. If it can be done with him, then why not others?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in