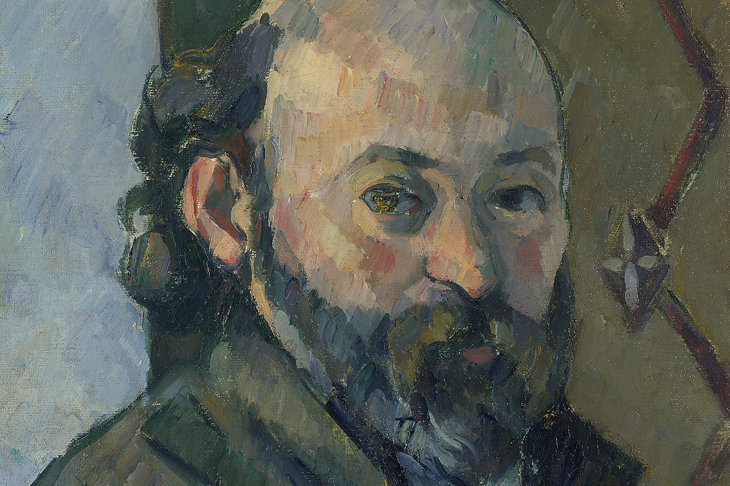

The critic and painter Adrian Stokes once remarked on how fortunate Cézanne had been to be bald, ‘considering the wonderful volume that he always achieved for the dome of his skull’. It’s a good joke, and all the better for being perfectly true — as is demonstrated by the superb sequence of self-portraits included in Cézanne Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery. These are the finest hairless craniums in the history of art.

That, however, is only one of the attractions of the exhibition. This is the most impressive array of work, by one of the greatest of all painters, to be seen in London in more than 20 years. Cézanne once said, ‘I paint as I see, as I feel — and I have very strong sensations.’ He makes us share them too.

You can absolutely sense how powerfully Cézanne perceived the roundness of his own head. The same is true of innumerable amazingly volumetric depictions of things in these pictures: the cylindrical coffee pot beside the ‘Woman with a Cafetière’ (c.1895), the thick, felt-like folds of the jacket worn by ‘Man with a Pipe’ (1891–6). It’s not hard to understand why the artist hesitated between the words ‘see’ and ‘feel’ when he made that remark. He creates an impression that one could just reach out and handle these objects.

This is perhaps why, in Cézanne’s own mind — and several other people’s — his portraits were connected with his paintings of still life. The art dealer Ambroise Vollard famously related that when he started shifting his position during one of the interminable sittings for the wonderful picture in this show of 1899, the artist protested, ‘Do I have to tell you again you must sit like an apple? Does an apple move?’ Others picked up on this — the writer Charles Morice, for example, who asserted that ‘Cézanne takes no more interest in a human face than in an apple.’

This, I suspect, wasn’t quite true. It was the case, though, that Cézanne was profoundly concerned with the qualities shared by human beings and fruit, such as roundness. Hence his celebrated advice to divide up nature into ‘the cylinder, the sphere and the cone’. In the catalogue, John Elderield, the curator, writes that when painting his wife, Hortense, Cézanne became increasingly obsessed with depicting her head as an ‘unimpeded oval’ even if that meant flattening her ears (‘a somewhat discomforting effect if one notices it’.)

Cézanne was not solely intent on reducing his sitters to a series of geometric solids. His fundamental aim in his portraits, as in all his work, was to ‘render what we actually see’. That is, not what we think we know or remember from other works of art but what is really there in front of the easel.

This made Cézanne an unusual sort of portraitist — in some ways, a modern one. Like Freud’s or Auerbach’s, his subjects were all people he knew well — family, friends, the workers on his family estate, the Jas de Bouffan. These were not public pictures, but what the painter Euan Uglow used to call ‘private research’.

Often they were not completed. Cézanne had the modernist problem with finishing a picture. You can understand why: ‘resolving’ the slightly blurred passages around the elbow and shoulder of ‘The Smoker’ (1893–6) might have hardened and deadened the total effect. ‘Finishing’ a picture, Picasso observed, can kill it stone-dead.

Cézanne was not interested in his sitters’ moods, dreams or social position. He was concerned simply with what was visible. This applied to his depictions of himself, which are — despite the handsome rotundity of his pate — utterly free of vanity.

The slow disappearance of emotion from his paintings of his wife may be the result of the numbing effect of posing for hundreds of hours. The earlier pictures show a shyly affectionate, almost animated young woman. It is only as the years go by that she becomes, as Elderfield puts it, ‘an automaton’ — or an apple. But then Cézanne’s true discovery, as D.H. Lawrence saw it, was the ‘appleyness’ of people.

Rilke used a different metaphor, writing that Cézanne painted himself a bit like a dog that had looked in the mirror and thought, there’s another dog! Actually, Cézanne was a bit like that with everybody he painted — looking at them as if a big, dressed-up animal had walked into his studio. It’s partly his ability to look at familiar people as if seeing them for the very first time that makes these pictures so extraordinary.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in